John and Craig discuss the other stuff screenwriters write, from beat sheets to scriptments and everything in between. The differences are sometimes subtle, but each can have value — in the right circumstance.

After that, they dip into the mailbag (24:23) for questions on TV bibles, writing while traveling, and using “I” in titles.

Premium subscribers: stick around for a bonus segment (47:31) on the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator and how its questions may be useful to screenwriters.

* John will be part of the [Beyond Bars: Changing the Narrative on Criminal Justice](https://www.eventbrite.com/e/beyond-bars-changing-the-narrative-on-criminal-justice-tickets-91710373195) panel on February 26th

* Contact [brand@johnaugust.com](mailto:brand@johnaugust.com) for information on [Highland 2](https://quoteunquoteapps.com/highland-2/students.php) for students and educators

* [Outlines](https://screenwriting.io/what-does-an-outline-look-like/) and [treatments](https://screenwriting.io/what-is-a-treatment/) on screenwriting.io, and some examples in the [johnaugust.com library](https://johnaugust.com/library)

* Scriptnotes, episodes [436](https://johnaugust.com/2020/political-movies), [434](https://johnaugust.com/2020/ambition-and-anxiety), and [432](https://johnaugust.com/2020/learning-from-movies)

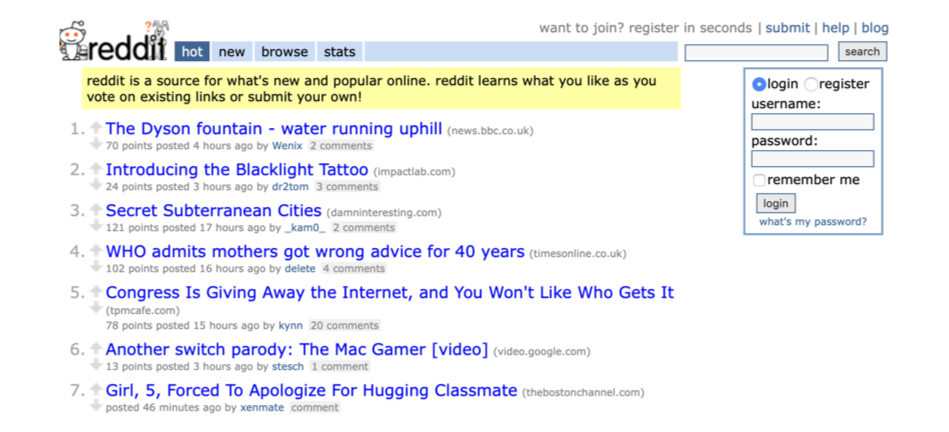

* Reddit’s [r/imsorryjon](https://www.reddit.com/r/imsorryjon/top/?t=all)

* Scott Silver on [IMDb](https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0798788/?ref_=tt_ov_wr) and [Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scott_Silver)

* The [Myers–Briggs Type Indicator on Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myers%E2%80%93Briggs_Type_Indicator) and an [online test](https://www.16personalities.com/)

* The [Big Five personality traits](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Five_personality_traits)

* [John August](https://twitter.com/johnaugust) on Twitter

* [Craig Mazin](https://twitter.com/clmazin) on Twitter

* [John on Instagram](https://www.instagram.com/johnaugust/?hl=en)

* [Outro](http://johnaugust.com/2013/scriptnotes-the-outros) by James Llonch ([send us yours!](http://johnaugust.com/2014/outros-needed))

* Scriptnotes is produced by Megana Rao and edited by Matthew Chilelli.

Email us at ask@johnaugust.com

You can download the episode [here](http://traffic.libsyn.com/scriptnotes/437standard.mp3).

**UPDATE 2-21-2020** The transcript for this episode can be found [here](https://johnaugust.com/2020/scriptnotes-episode-437-other-things-screenwriters-write-transcript).