*On October 24, 2019, I presented the Hawley Foundation Lecture at Drake University. It was an update and reexamination of a 2006 [speech on professionalism]((https://johnaugust.com/2006/professional-writing-and-the-rise-of-the-amateur)) I originally gave at Trinity University, and later that year at Drake.*

*What follows is a pretty close approximation of my speech, but hardly a transcript. It’s long, around 14,000 words. My presentation originally had slides. I’ve included many of them, and swapped out others for links or embedded posts.*

*If you’re familiar with the earlier speech and want to jump to the new stuff, you can click here.*

—

Back in 2006, I gave a speech here at Drake entitled “Professional Writing and the Rise of the Amateur.” In it, I presented my observations and arguments about how the emergence of the internet had made the old distinctions between amateurs and professionals largely irrelevant. Tonight I want to revisit that speech and look at what still makes sense in 2019, and more importantly, what I got wrong.

To do that, we need to start with a bit of time travel so we can all remember what 2006 looked like.

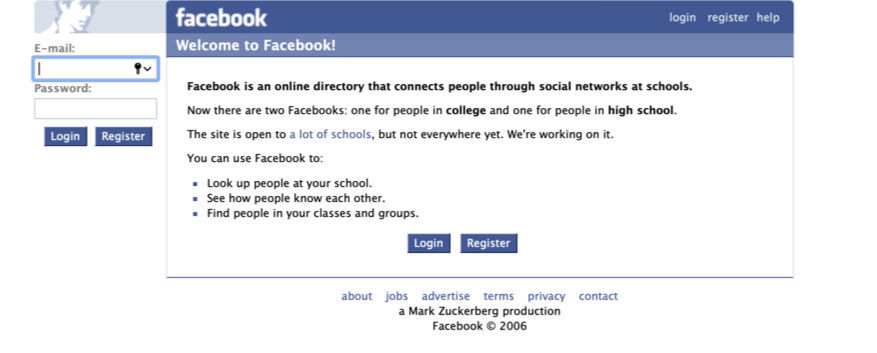

Here’s Facebook:

Here’s Twitter:

Here’s Netflix:

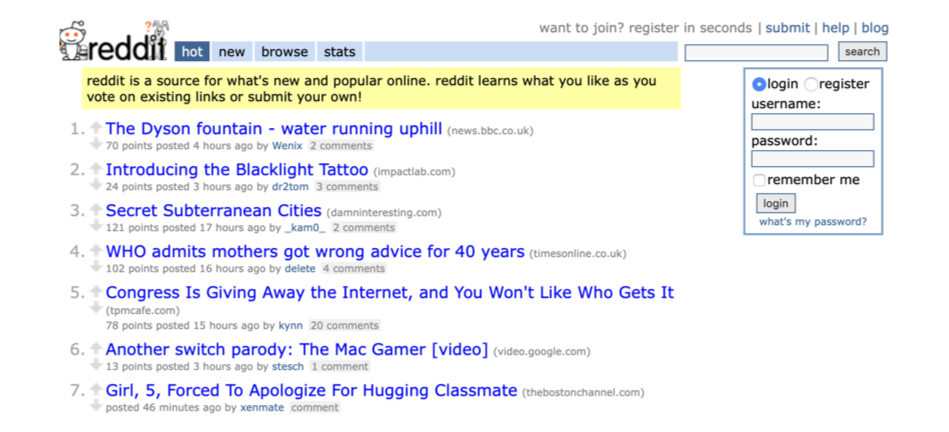

Here’s Reddit:

Here’s Instagram:

Oh, 2006 was a simpler time. The internet existed, but it wasn’t as all-consuming as it is now. We had blogs. We had MySpace. But we didn’t have the internet on our iPhones. Because iPhones wouldn’t come out for another year.

However, even in this innocent age, issues would arise that would feel very familiar today. We had fake news and trolls and pile-ons.

For example, back in 2006, I started my speech with this anecdote:

> On March 21, 2004, at about nine in the morning, I got an email from my friend James, saying, “Hey, congrats on the great review of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory on Ain’t It Cool News!”

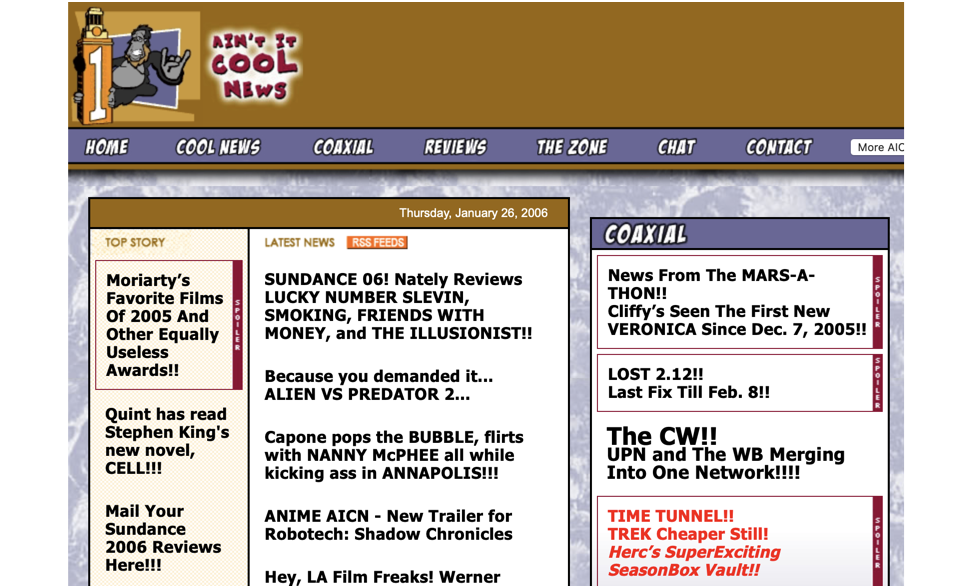

Let’s start by answering, What is Ain’t It Cool News? It was a movie website started by a guy named Harry Knowles. It looked like this:

Ain’t It Cool News billed itself as a fan site. I’d argue that it was an incredibly significant step towards today’s fan-centered nerd culture, for better and for worse. Online fandom has brought forth the Avengers and fixed Sonic the Hedgehog’s teeth, but it’s also unleashed digital mobs upon actors and journalists, women in particular.

Back in 2006, the nexus of movie fandom was Ain’t It Cool News. It wasn’t just a barometer of what a certain class of movie fan would like; it could set expectations and buzz. Studio publicity departments checked it constantly.

So, back to my email from James. He’d written:

> “Hey, congrats on the great review of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory on Ain’t It Cool News!”

This was troubling for a couple of reasons.

First off, the movie hadn’t been shot yet. We weren’t in production. So the review was actually a review of the script. Studios and filmmakers really, really don’t like it when scripts leak out and get reviewed on the internet, because it starts this cycle of conjecture and fuss about things that may or may not ever be shot. So I knew that no matter what, I was going to get panicked phone calls from Warner Bros.

I click through to Ain’t It Cool and read this “review.” And it’s immediately clear that it’s a complete work of fiction.

The author of the article, “Michael Marker,” claims to have read the script, but he definitely hasn’t. He’s just making it up. It is literally fake news.

Fortunately, back in 2004, I knew exactly one person at Ain’t It Cool News. His name was Jeremy, but he went by the handle “Mr. Beaks.” So I emailed him, and say, hey, that review of the Charlie script is bullshit.

Actually, I don’t say that. I say, “That guy is bullshitting you.” It’s not that I’m wronged, no. It’s that that guy, Michael Marker, is besmirching the good name of Ain’t It Cool News by trying to pass off his deluded ramblings as truth. How dare he!

And it works. Mr. Beaks talks to Harry Knowles, and Harry posts a new article saying that the review was bogus.

They don’t pull the original article, but oh well. It’s basically resolved.

I can’t help but think — this article was wrong, but it was really, really positive. What if it had been negative? Would Mr. Beaks or Harry Knowles have believed me? Probably not. They would have said, “Oh, sour grapes.” My complaining would have made the readers believe the bogus review even more.

It might have led to the [Streisand effect](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streisand_effect), where complaining about something just brings more attention to it.

Back in 2006, if you tried to really go after any of these film-related sites, criticizing them for say, running a review of a test screening or just outright making shit up, you’d get one standard response:

> Hey, we’re not professional journalists. We’re just a bunch of guys who really love movies.

Their defense is that they’re amateurs, so they can’t be held to the same standards of the New York Times or NBC.

That became the topic of my speech in 2006: the eroding distinction between professionals and amateurs.

The classic, easy distinction is that the professional gets paid for it, while the amateur doesn’t. For a lot of things, that works. You have a professional boxer versus an amateur. You have a professional astronomer versus an amateur — some guy with a telescope in his back yard.

But the “getting paid for it” test doesn’t hold up to much scrutiny. An amateur photographer can take a picture that ends up in Newsweek. That doesn’t make them a professional. And “Michael Marker” might not be getting paid by Ain’t It Cool News, but he was getting something out of writing that article: a measure of recognition, and, ironically, credibility.

This led to my first thesis.

## “Professional” has nothing to do with getting paid.

So if it’s not money, what is the difference between amateur and professional?

A friend tried to make the distinction that, “The amateur does something for the love of it.” Which is kind of defeatist if you think about it. Like, the minute someone pays you for doing what you love, you stop loving it. I don’t think it’s a universal by any means. How we feel doesn’t neatly correlate with how we’re paid.

After twenty-odd years, I feel exactly the same way about screenwriting now as when I first started, back when I was sleeping on the floor and eating Ramen Noodles. That is: I kind of hate writing, but I love having written. I would rather do almost anything than sit down and write a scene. But having written it, then reading it back? Pure gravy.

Still, my friend had a point. The word “amateur” really does have something to do with love.

‘Amateur’ comes from the French *amateur* — one who loves — which tracks back to the Latin verb for love (amare).

In contrast, a ‘professional’ was originally someone who had to profess an oath to become a member of their occupation, such as a doctor, a lawyer or a priest. To make such a promise is a serious undertaking.

In the case of doctors and lawyers and priests, there’s a ruling body to whom you profess your oath. But if you don’t have an organization like that, who are you professing to? Who’s holding you accountable? And what exactly are you pledging?

When we say “professional” in the modern context, I think what we’re really talking about *professionalism:* a bundle of expectations about how you’re supposed to act.

Back in 2006, I listed five key characteristics to describe professionalism.

The first is **Presentation.** Let’s say you write a business email, and it’s full of typos and grammatical mistakes. Not professional.

Or you’re a funeral home director, and you sit down with the grieving family while wearing a Ramones t-shirt. Not professional.

Obviously, what I’m getting at is that there’s an expectation about how professionals present themselves, either in person or in writing. You want to make sure that your audience sees you in your best light, which means spell-checking and putting on a clean shirt.

The second characteristic we’re talking about when we mean “professional” is **Accuracy.**

If you’re an accountant, and you misplace a decimal point, that’s unprofessional. If you’re a surgeon who amputates the wrong arm, that’s inaccurate, and unprofessional. And really awful.

The third characteristic is **Consistency.**

Let’s say you go to a restaurant, and they serve really good Mexican food. The next time, it’s pretty bad. But you go back anyway, and this time they serve only Hungarian food.

You’re not likely to go back a fourth time. Part of professionalism is consistency. It’s delivering what people expect every time.

And of course, showing up on time. If the only thing you’re consistent in is “consistently late,” then that’s not professional.

Next, **Accountability.** That means, when asked the question, “Who did this?” You can raise your hand and say, I did. I was responsible. Accountability is sort of the opposite of anonymity. It’s why you see bylines on newspaper articles.

For Ain’t It Cool News, most of these articles were written under pseudonyms, so there was less accountability to each individual writer. And the site as a whole seemed to have no fact-checkers or ethics board. Like most things on the internet, it had arisen organically, and grown into prominence without a lot a critical thought about its role and responsibilities.

In my 2006 list, the last characteristic of professionalism I listed was meeting **Peer Standards.**

By that I meant that within the class of people doing what you’re doing, there’s consensus about what’s acceptable and what’s not. Sometimes, that’s codified, like Realtors with a capital-R, or lawyers and the bar association. A lot of times, it’s less formal, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there. Whether it’s waiters sharing tips with the busboys, or undergraduates sharing notes before a test, there’s pretty clear agreement about what’s okay and what’s not. And probably more importantly, some consequence if you don’t meet the standards of your peers.

In 2006, what were the peer standards for a website like Ain’t It Cool News? It wasn’t clear. We had just begun to grapple with the reality that anyone could publish a site that competed directly with legacy media like newspapers and magazines.

So to review, here’s what I originally included in my definition of professionalism:

1. Presentation

2. Accuracy

3. Consistency

4. Accountability

5. Peer standards

It’s not a bad list per se, but I think there are some real problems and oversights I want to correct for 2019.

## The problem of presentation

It seems uncontroversial to suggest that being a professional means looking and acting like a professional.

But wait: Who defines what “looking” like a professional means? What is professional attire? For a lawyer in the courtroom, it might mean a suit and tie for a man. But what about for a woman? A dress? Okay, define that dress. What color is it? Where’s the hemline? Is it appropriate for a woman to wear a suit and tie?

And then there’s the issue of hairstyle. What’s professional? Is an afro professional? How about a headscarf? Is it acceptable to have your hair dyed bright green? Why or why not?

How about tattoos? How about piercings?

In 2006, I wasn’t paying nearly enough attention to the reality that most of what we think about in terms of professional presentation is centered around the needs and tastes of straight white men. You can’t simply invite women, or people of color, or people with different gender identities into a profession and expect them to adopt the dress and stylings of the white dudes who were there first.

Of course, it goes beyond what someone looks like. People present themselves in words. So which words are professional? In 2006, I didn’t think nearly enough about how people code-switch when talking and writing. It’s common for people to talk one way with members of their community and a very different way in other contexts.

If Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is talking with her constituents, which style of speaking should she use? The one she uses in the House of Representatives, or the one she uses in her actual house? A “professional tone” depends on context and audience. We can’t set the default at “40-year-old white guy at IBM.”

The notion of professional presentation wasn’t wrong — how you look and act still counts — but I hadn’t adequately considered the degree to which norms and standards can be used as a cudgel against outsiders.

## Accountability isn’t just fact-checking

In 2006, I was thinking of accountability in terms of the public work we see someone do — bylines on newspapers, holding senators to their word — but in the wake of #MeToo and other whistleblowers, it’s abundantly clear that accountability for private actions is also important.

In 2019, we’re reckoning with terrible behavior that went unreported and unacknowledged for far too long. But we’re also dealing with old tweets stripped of their context, and regrettable choices we can’t escape because the internet is forever.

For example, consider [my 1996 website](http://johnaugust.com/1996). It’s cringe-worthy. It has a poetry corner! The very mid-90 site doesn’t represent who I am now, but by the principle of accountability, it should still count as evidence. I chose to put those HTML tables out into the world.

We’re just starting to grapple with how to handle past words and deeds. This fall, comedian Shane Gillis was un-hired from SNL for recent racist comments. That seemed fair to me.

But what do we do with someone who never intended to become a public figure? Consider the scenario in which a brave first-responder becomes a national hero. Once they’re thrust into the spotlight, what’s fair? Should they be called to answer for a decade-old anti-immigrant tweet? And if so, are they still a hero, or a villain, or something else?

As a precaution, many of us delete old tweets, worried they’ll be weaponized against us. I worry we’re erasing ourselves in the process.

## Your peers aren’t a great measure

When I included “peer standards” in my initial list, I was focused on “the people who do what you do.” But in hindsight, I’m not sure that’s the best or only group to look at, for two reasons.

First, your peers may be terrible. If you’re only aiming to be as professional as other tabloid journalists, you’re setting the bar really low.

Second, you may have other stakeholders who are more important than your peers. You probably have an audience, or customers, or constituents. You have suppliers. Employees. If you’re only worried about what your competitors are doing, you’re likely to do some pretty crappy things.

So for 2019, I’d change peer standards to **Community Standards**.

## Consistency is too narrow

While I’m editing this list, I’d change consistency to **Reliability**. This word encompasses everything consistency does, and adds the twin notions of trust and integrity, by which I mean “being honest” or “doing what you say you’re going to do.”

For example, as a screenwriter, you make money two ways.

The first is when you write an original screenplay and sell it. In this case, the studio is looking at the finished script and judging how much to pay based on what they read. They’re paying for the script, not the writer.

The other way a screenwriter makes a living is by being hired to write a movie, perhaps based on a book or some previous piece of material. In this case, the studio is deciding how much to pay you based not the words you’ve written, but on the words you’re going to write.

Yes, they’re paying for quality, but just as importantly, they’re paying for reliability. They want to know that the money they spend is going to result in a script they can shoot as a movie. Consistency is worth a lot.

## Late additions

In addition to these edits, there are three qualities I didn’t include on this list that I realize now are very important.

I’ll start with **Humility**, which was suggested by Craig Mazin. (Part of humility is acknowledging others for their good ideas.)

Humility to me means recognizing the limits of your knowledge and proficiency. That’s not simply couching everything in, “It’s just my opinion but…” It’s actively recognizing that you could be wrong. That your plan may fail. That others may have better ideas.

Humility is likely the best defense against becoming a crank. You know what I mean: sort of an expert asshole. Cranks have an opinion and they’re not open to changing it. They’re not curious because they’re damn sure they’re right.

Beginners often have a health dose of humility because they’re aware there’s a lot they don’t know. It’s the experts who are often lacking in humility, which can lead to blind spots.

The next two are suggestions from my friend Phil Hay.

A professional needs to be committed to **Dignity** — both their own dignity and that of others. Dignity encompasses respect and acceptance of differences. It means looking at other human beings as human beings, whether they’re coworkers or competitors, noisy neighbors or angry customers.

Dignity is a simple restatement of the Golden Rule: treat others how you wish to be treated, and treat yourself with that same respect.

In my first few years after college, I didn’t believe I deserved to be treated respectfully. I let bosses take advantage of me. I didn’t speak up when I saw them engaged in petty mistreatment. They were acting unprofessionally, but I was too: I was making excuses for why I wasn’t calling out abuse.

Basically, I wasn’t expecting dignity for myself or others. This deficit goes hand-in-hand with the final item on my revised list: the need for **Proper Boundaries**.

In life you have friends and family, coworkers and romantic partners. At times, people will move between these categories. You’ll go into business with your brother-in-law. You might fall in love with the person at the next desk like Jim and Pam in The Office.

But professionalism means not assuming that someone wants to change categories. In fact, the default assumption has to be that they don’t. Only with a preponderance of evidence should one ask, and then only with clear exit paths so no one feels cornered.

The same way you need boundaries between roles, you need proper boundaries in time. Part of professionalism is recognizing that people have lives outside of work. Most jobs should not be on-call 24/7. Some companies have explicit policies about weekends and after-hours work, but the same logic should apply when talking with a supplier or client.

Proper boundaries are important online as well. The fact that you **can** contact someone doesn’t mean you **should**. When we were both assistants, a friend of mine showed me Kevin Costner’s phone number. It was in the Rolodex. It would feel so weird to call him, right? But on Twitter, you can reach out to any celebrity at any time. That doesn’t entitle you to a response.

But I want to distinguish harassment from hustle. Sometimes you distinguish yourself by carefully crossing boundaries.

An example: In film school, a classmate and I were in the elevator with a studio chief. My friend reached out his hand and said, “Hi, Joe. I’m Jon Glickman and I really want to work for you.”

Was that appropriate? Was it professional? I don’t know. It made me very uncomfortable. But Jon Glickman got his job. A few years later he was running the studio.

People often observe that millennials are less concerned about professional hierarchies and protocols, so maybe Jon was an early millennial. I think it’s worth being conscious when you may be crossing a boundary, and to ask yourself how and whether it makes sense to do so.

You don’t always have to respect the fences. But before you climb over one, stop and think. Maybe get a second opinion.

## The New List

So now we have a handy list of eight characteristics of professionalism:

1. Presentation

2. Accuracy

3. Reliability

4. Accountability

5. Community Standards

6. Humility

7. Dignity

8. Proper Boundaries

What do we do with it? How do we go from these ideals to the real world?

Basically, how do you act professionally?

Let’s go back to my 2006 speech. Here’s one of my takeaways.

**You don’t get to pick when you’re going to be professional, and when you’re going to be amateur.**

Maybe the best way to prove this is to think back to when you were in high school geometry class. Which for some of you, was like, last year. Remember, there are two kinds of proofs? There are direct proofs, where you follow from your postulates and axioms to prove something, and then there’s the indirect proof. For the indirect proof, you assume the opposite, then follow it through until it reveals itself to be illogical.

This is an indirect proof.

So let’s say, okay, you do get to decide when you’re going to be an amateur, and when you’re going to be a professional. Let’s follow that logic through.

What do you get out of identifying yourself as a professional?

**Access.** If you’re a professional photographer, you might get access to a news event that an amateur wouldn’t. Credentials can literally get you in the room.

**Payment.** You might get paid, so you can earn a living doing this. As a professional screenwriter, I get paid pretty well for writing witty dialogue. A professional actor gets paid a lot more for saying the witty dialogue I wrote, but that’s another issue.

**Respect.** As a professional, you also get the respect of your peers. You get to sit at the grown-up table, rather than the kiddie table. In terms of life-satisfaction, that can be worth a lot.

Clearly, there are a lot of reasons why you want to be considered a professional.

What do you get out of identifying yourself as an amateur?

**Access.** It’s sometimes actually easier to get in the door when you’re not identified as a professional. The gatekeepers don’t see you as a threat. It’s part of the reason internships are so valuable. You get to be a fly on the wall.

**Lower stakes.** If you’re an amateur astronomer and you identify a new asteroid that turns out to be a smudge, you’re not going to be drummed out of the star-gazing club.

**Easy exit.** As an amateur, you can just walk away. If you decide you don’t enjoy playing Fortnite anymore, just stop. But if you’re making your living as a professional videogamer in competitions and on Twitch, it’s not so easy to quit.

So back to our indirect proof: let’s say you have a choice whether to be a professional or an amateur.

When would you choose to be a professional? Well, probably when you’re doing your best work. The work you feel confident about. Good about. It’s easy to be a professional when everyone says you rock.

When would you choose to be an amateur? Well, probably the moments in which you obviously suck, either because you don’t know what you’re doing, or you’re just not very good at it. Or at least in the moments when people are criticizing you. You’d say, “Hey, what do you expect? I’m only an amateur.”

That sounds like Ain’t It Cool News. It’s using amateur status as an excuse. You’re basically saying, “Don’t judge me.”

And here’s where this indirect proof falls apart: **People will always judge you.** You can’t control that. You can’t control what scale they’re going to judge you on, or which criteria they deem most important.

My original thesis was, “You don’t get to decide when you’re going to be professional, and when you’re going to be an amateur.” We can shorten that.

**You don’t get to be an amateur at all.**

This is more true now than when I first said it in 2006.

An example: In 2013, a PR rep named Justine Sacco sent a tweet before getting on an 11-hour flight from London to South Africa.

> “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!”

She only had 170 followers, but the tweet went viral. By the time her flight landed, an online mob was demanding she be fired. She ultimately was.

Jon Ronson wrote a [great book](https://amzn.to/2qtndBA) about this type of public shaming and how it seems all of us are one ill-considered joke away from ignominy and ruin.

To me, the more useful lesson is the reminder that we’re always being judged based on our profession, even if we don’t think we’re on the clock. I don’t believe Justine Sacco would have found herself in the same predicament if she were a bartender or carpenter. It’s because she worked in media that she was vulnerable. This tweet was considered part of her work.

You can’t control how the world reacts. The only thing you can control is your work.

I’m going to repeat this.

**The only thing you can control is your work.**

That’s why your work, all of your work, has to be professional.

I made the same point back in 2006. It was a time of bloggers, basically. One person with a website could draw a huge audience for a narrow topic. You saw this with Andrew Sullivan and Talking Points Memo for politics. You had Jezebel, Perez Hilton and Go Fug Yourself for celebrity gossip. Daring Fireball for Apple-related things. Each of these sites was hugely influential.

But what we didn’t have back in 2006 was the notion of an influencer. That’s a fairly recent addition.

## Identity as industry

These early blogs and websites were run by people, sometimes flamboyant personalities, but ultimately they were like newspaper columnists or radio talk show hosts in print form. They were renowned for their content, for what they said, not their existence.

The arrival of the influencer changed that.

Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman became famous for being actors. Their ongoing fame helps perpetuate their acting careers. They are actors first, brands second.

Influencers are simply brands. They use their internet fame to monetize directly, not through another career but through the attention they can create. The clicks they can generate. The fans who can buy their products.

Now, to be clear, there were always influential people. In marketing class, we might call them thought leaders or opinion leaders. They tend to be experts in a given field (Neil deGrasse Tyson), or highly connected within their community (a sorority president).

Influencers are slightly different. The most successful ones manage to feel like they’re old friends who just happen to always be beautifully lit.

Consider [Jack Morris](https://www.instagram.com/doyoutravel/) and [Lauren Bullen](https://www.instagram.com/gypsea_lust/). They’re travel influencers. Each with their own Instagram and YouTube accounts. They live in Bali and Los Angeles. They travel a lot. He seems to have a hard time buttoning his shirt.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B2q6ZUNBp0v/

In some ways they feel like professional amateurs. They’re just two beautiful people traveling around.

But then you realize how much of what they’re doing is sponsored by someone else. This is their business, and they’re treating it like professionals. Let’s look at what they’re doing in light of our professionalism checklist.

**Presentation:** Jack and Lauren are all about presentation. Clothes, hair, makeup, lighting, filters. They’re editing hundreds of photos to get the one that works best.

But it goes beyond how it looks. They’re careful to present their relationship in a specific way. I have a hunch they plan how often they’re in each other’s shots, and what percentage of posts have product placement versus being “real.”

**Accuracy:** Jack and Lauren are often being paid to promote a specific brand on a specific day. If they mess up, they’ve lost thousands of dollars and a potential future customer.

**Reliability:** Could Jack and Lauren post a photo of Kraft macaroni and cheese? No. It would be off-brand. They have built their following by reliably showing two hot white people in beautiful locations. If they were to switch it up, they’d break that social contract. They’d lose the sense of trust.

**Accountability:** Is this really Jack and Lauren’s favorite rug shop in Cappodocia? I don’t know. I kind of doubt it. I think there are real questions of accountability when it comes to influencers, because it’s never really clear what they honestly think.

**Community Standards:** Influencers don’t have to pass the bar or take the Hippocratic Oath. Beyond Instagram’s terms of service, the norms and standards of the community are constantly changing. How much can be automated? How much Photoshop is okay? Could Jack simply Photoshop himself into this image?

In this image, Jack is being paid to promote tourism to Abu Dhabi. Are there countries he wouldn’t take a sponsor?

**Humility:** Jack and Lauren are constantly asking their followers for feedback and advice. Are they taking it? Who knows. Despite having a glamourous-seeming lifestyle, they take pains to sound ordinary.

**Dignity:** Tourism is knocked for giving a shallow view of the cultures you’re visiting, and treating locals more like set dressing than human beings.

For better or worse, Jack and Lauren don’t include many residents in their shots. The few I’ve found don’t identify anyone by name, and seem mostly there to provide contrast. If Jack and Lauren are engaging with citizens as people, it’s not showing up in their photos.

**Proper Boundaries:** Jack and Lauren seem to be selling the fantasy of their coupledom as much as any location or product. As influencers, what part of their relationship is out of bounds? If they broke up, what would happen to their business?

Like a lot of social media entrepreneurs, they engage with their fans, but how much is too much? Do they need to worry about their safety and privacy? What about the privacy of their friends and family, who are likely only a few Google searches away?

# Takeaway

One huge difference between college students today versus 2006: You grew up in this. I’m not describing some scary, unfamiliar world. I’m just challenging you to think about what it means to do your professional work in this environment.

Honestly, truly: If you feel like writing a 5,000 word Medium post about your cat, go for it. I’m just asking you, pleading with you, to spellcheck. Mr. Whiskers deserves it. Tuck in your virtual shirt and take even the frivolous stuff seriously.

Let me talk about an example from my own experience:

The very first script I wrote was called Here and Now. It was a romantic tragedy set in Boulder, Colorado. It was your classically overwritten first script, where I tried to cram in everything I knew about everything, because there’s that sense of, maybe I’m never going to write another script, so I better put it all in this one.

The script turned out well, and was ultimately good enough to get me an agent, and eventually got me a paid job writing a script for somebody else.

Now when I go back and read the script, I wince. I’m a better writer now than I was then. But I’m not ashamed of that script, because it’s professional. Presentation-wise, there are no egregious typos. It’s accurate, at least about the emotional details. It’s consistent; in screenwriting, there are a few acceptable ways of formatting things, and any of them are okay, as long as you pick one and stick with it. I still feel accountable for the script. I don’t send the script out any more as a sample, but if someone’s read it, I’ll still happily talk about my choices. The writing shows the appropriate degree of humility and dignity for the characters. When it was time to show it around, I respected boundaries. I didn’t foist it on friends who didn’t really want to read it.

And finally, this is the important thing: the script met community standards. Even though I was a newbie screenwriter, I wasn’t trying to write for other newbie screenwriters. I was writing as if I were a professional screenwriter, and I wanted people to read it that way.

I do that because it has my name on it. I think you need to look at your name as sort of your brand, just like Jack and Lauren. They don’t want to be associated with ugly photos, I don’t want my name associated with bad, unprofessional writing.

## What should we profess?

So, we said at the start that “professional” comes for Latin for profess, to take an oath. If you were take an oath to be a professional, what might it include?

**Listen before speaking.**

Learn the lingo, the codes, the shibboleths. Hang out in the forums. Subscribe to the newsletters.

For Arlo Finch, that meant following other middle-grade authors on Twitter. I asked my editor what pitfalls to watch out for, particularly with grade school librarians and booksellers.

**Ask smart questions.**

A smart question is one you can’t find in the frequently asked questions. One for which there probably isn’t a single correct answer, but that exposes the way a professional thinks about an issue.

In the summer of 1993, I had an internship at Universal Pictures, working for the head of physical production. She was a legend. She had line produced Terminator. My job was to file a bunch of stuff. It was boring. So made a game of reading everything I was filing and trying to see if I could ask one smart question each day.

The best opportunity was after lunch, when my boss hadn’t yet settled into her next project. I’d show her a budget for The Flintstones movie and ask why they’d budgeted in overtime in some areas and not others.

I wasn’t asking “how do budgets work?” or “why is there overtime?” I was asking about the decision process. I was taking the question seriously. At the end of the summer, Universal offered me a job and I knew I didn’t want. I could say that honestly because I knew a lot about the physical production department.

**Set standards for yourself.**

If you’re entering a profession that doesn’t have an existing code, make one for yourself.

What are your working hours? How often will you schedule a meeting with your boss about advancement? What clients will you decline to work with? It’s so much easier to make an ethical decision when you’ve written down your principles in advance.

An example from my experience: I don’t disparage other filmmakers or their work. If I’ve had a bad experience with someone, I’ll be diplomatic when asked about them and try to provide context. If I hated their movie, I’ll frame my comments in terms of my reaction rather than their failure.

Again, it comes back to the Golden Rule. I treat others the way I hope they’d treat me.

In closing, I want to say that we’re actually living in one of the most exciting times in media history. Yes, I said this in 2006, but it’s still true. The barriers to entry have never been lower. You can make a seven second video and be a worldwide sensation in hours. With social media, you can respond to readers and viewers in ways you never could before.

Technology changes, but the change itself is constant.

I was at Drake in the early 90s, when we suddenly had laser printers. I was a graphic designer, so I was in heaven. But in addition to all that great work there were a lot of crappy newsletters. And we learned a painful lesson: Just because you can make a newsletter with 50 fonts on the cover, doesn’t mean you should.

The same held true for blogs. For YouTube. For Vine, rest in piece. For Instagram and all the next things coming. Suddenly, these incredibly powerful tools will allow amateurs to do things that once seemed inconceivable.

What I’m asking, what I’m pleading for, if you can read my subtext, is that we approach these new tools not like amateurs, but like professionals. Unlike that crappy newsletter, which got recycled, your tweet is going to be around forever on some Chinese server. Forever. Historians will study it and wonder, “Jesus. Couldn’t they proofread before hitting send?”

No matter what career you end up choosing, you will be doing something for the rest of your life. Make a promise to yourself tonight that whatever it is, you’ll always treat it as a professional.

Thank you.