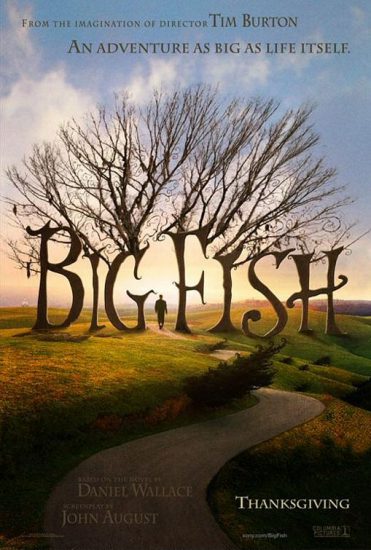

This afternoon, I came across the letter I wrote in 1998 trying to convince Columbia Pictures to option the rights to Daniel Wallace’s novel Big Fish for me to adapt.

It’s strange seeing this letter now. In it, I describe the very broad shape of the movie, but at the time I didn’t know so many of the details. Crucial elements like the circus, the war, Josephine, Norther Winslow — none of these existed in the book, and I had at most a vague sense of what I wanted to do.

At the time, there were no producers involved, and no director. It was just me and the studio.

The truth is, this letter probably didn’t convince anyone. Columbia wanted me under contract so they could have me work on other more-commercial movies. But it served an important role in convincing myself that there really was a movie to make out of Wallace’s weird and delightful little book.

To: Readers of Daniel Wallace’s BIG FISH

From: John August

Date: 9/14/98

RE: This book

I come to you with an unfair advantage: I read BIG FISH a few weeks ago, whereas many of you probably only read it last night or this morning. Trust me — it’s the kind of book that sticks with you and gets better as you think back through it. But since you probably don’t have the luxury of weeks to mull it over, I wanted to tell you why I liked this book so much when I first read it, and like it even more as I look back.

If you’re reading coverage of this book, the logline probably includes the words dying father and humorous anecdotes, which sounds suspiciously like the TV Guide listing for a Hallmark Hall of Fame movie that would be nominated for an Emmy, even though nobody you know actually saw it. The problem with that logline is that while it’s technically correct, it’s absolutely wrong.

BIG FISH is the story of Edward Bloom, a charming pain in the ass, as told by his immensely frustrated son William, who in the absence of any concrete history, can only tell us the wild exaggerations his father has been shoving upon him his entire life.

Edward Bloom feeds his son the kinds of stories you tell a wide-eyed five-year old — how you used to walk to school five miles, uphill each way. But now his son is in his 30’s, and Bloom never stopped telling these stories. Rather, he kept embellishing them, until they became a second life of sorts — perhaps the one he secretly wished he had lived. We pick up the tale as the elder Bloom lies on his deathbed, but the question of the story is not “will he die?” but “will he finally drop the facade?”

At this point, I have to digress and tell an anecdote from my life. (This is the kind of book that inevitably makes you want to talk about your own life; it stirs up strange recollections.)

On a dark rainy night in production on GO, I was sent off to set up a second-unit shot with a talented young actor who is, moment for moment, one of the funniest people I’ve ever met. ((Jay Mohr.)) The problem is, he doesn’t shut up. It’s as if every sensory input is channeled through a part of his brain that seeks humorous output. This life-as-Groundlings-sketch is charming at three in the afternoon, but at three in the morning, when you’re cold and exhausted and first unit has the lens you really really need, you find yourself searching for the switch that turns him off. Would you please just stop being funny so we can do this fucking shot?

In BIG FISH, William has the same frustration with his father: Would he please, just for once, not make a joke of all this?

Even as Edward Bloom amuses us, we can understand why William is annoyed. And honestly, if we had to spend an entire movie with this old man, we might get sick of him too. But the special treat of this movie is that you spend most of it with Bloom as a young man, tracking his life from impossible story to impossible story. He’s a modern-day Paul Bunyan, funnier for the inconsistencies in his tales.

If it sounds like I’m downplaying the dramatic elements, I’m not. Like FORREST GUMP or ORDINARY PEOPLE, there’s honest emotion at its core, and a movie shouldn’t shy away from that. I lost my own father at 21, and can remember sharply the months of walking on eggshells, and the weird power dynamics of a household built on maintaining tranquility at any cost. ((I was 28 when I wrote this. I made Will my age and Edward my father’s age so I could keep track of the timelines.))

Because even as they’re fading, people can piss you off. Just because you’re dying doesn’t give you an excuse to be an asshole.

While Edward spends his life trying to convince his son what a great man he is, William just wants to see a glimpse of the real man behind the bravado. In the end, neither wins, but there’s a more fundamental truth to be learned: even if you never really understand a man, that doesn’t keep you from appreciating him. ((This thesis gets restated different ways in the movie, including “My father and I were strangers who knew each other very well.” and “You become what you always were: a very big fish.”))

Now that I’ve rhapsodized about the book’s many virtues, let me note that it isn’t perfect. The individual anecdotes don’t always thread together especially well, and need to be more consistently (a) funny and (b) relevant. Properly told, we should see the reality behind the wild exaggerations. Even though we see the “myth” of Bloom’s life, there’s truth in the lies.

I’m not crazy about the ending; magical realism is a tough sell, and almost always feels like a cheat. But I think we can have it both ways. My instinct is to let Bloom die the way actual people die — quiet and peacefully — then show his death the way he would want us to believe: a funny, cataclysmic event that burns down half the town and coincidentally resolves many of the loose threads from his various stories.

I hope these ramblings give you a forecast of what you might be thinking about this book a week or two from now. Likely you’ll have your own anecdotes, because Wallace has the weird ability to feel universal and highly specific, as if he stumbled across some secret trove of shared histories.