Everyone loves links!

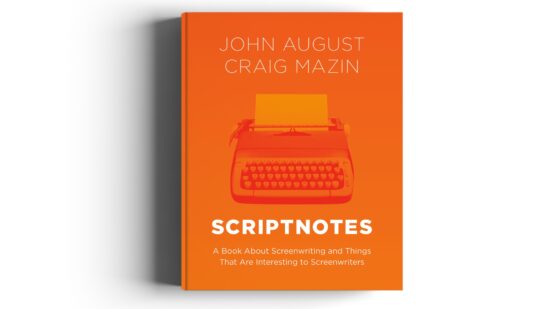

The Scriptnotes Book

Twelve years in the making, the Scriptnotes Book distills everything most a lot of what we’ve learned and discussed on the podcast into a handy book form. Available December 2, 2025, it’s a perfect gift for the screenwriter in your life (including yourself).

The hardcover book is 325 pages and 43 chapters on the craft and business of screenwriting. It also features interviews with some of our favorite guests.

Available now for preorder worldwide! → scriptnotesbook.com

Highland Pro

Highland Pro is the app my company makes for screewriters. Every word I’ve written for the past 10 years has been in Highland. The new version is incredible.

You can get Highland Pro for Mac, iPad and iPhone on the App Store. It’s much better than Final Draft, at a quarter of the price.

Birdigo

Birdigo, our very fun Wordle × Balatro game is now on Steam!

johnaugust.com

My screenwriting blog, where you can also see my credits.

Scriptnotes

Scriptnotes, my weekly podcast with Craig Mazin. We have amazing t-shirts and hoodies!

Writer Emergency Pack

Writer Emergency Pack, the perfect gift for any writer (including yourself).

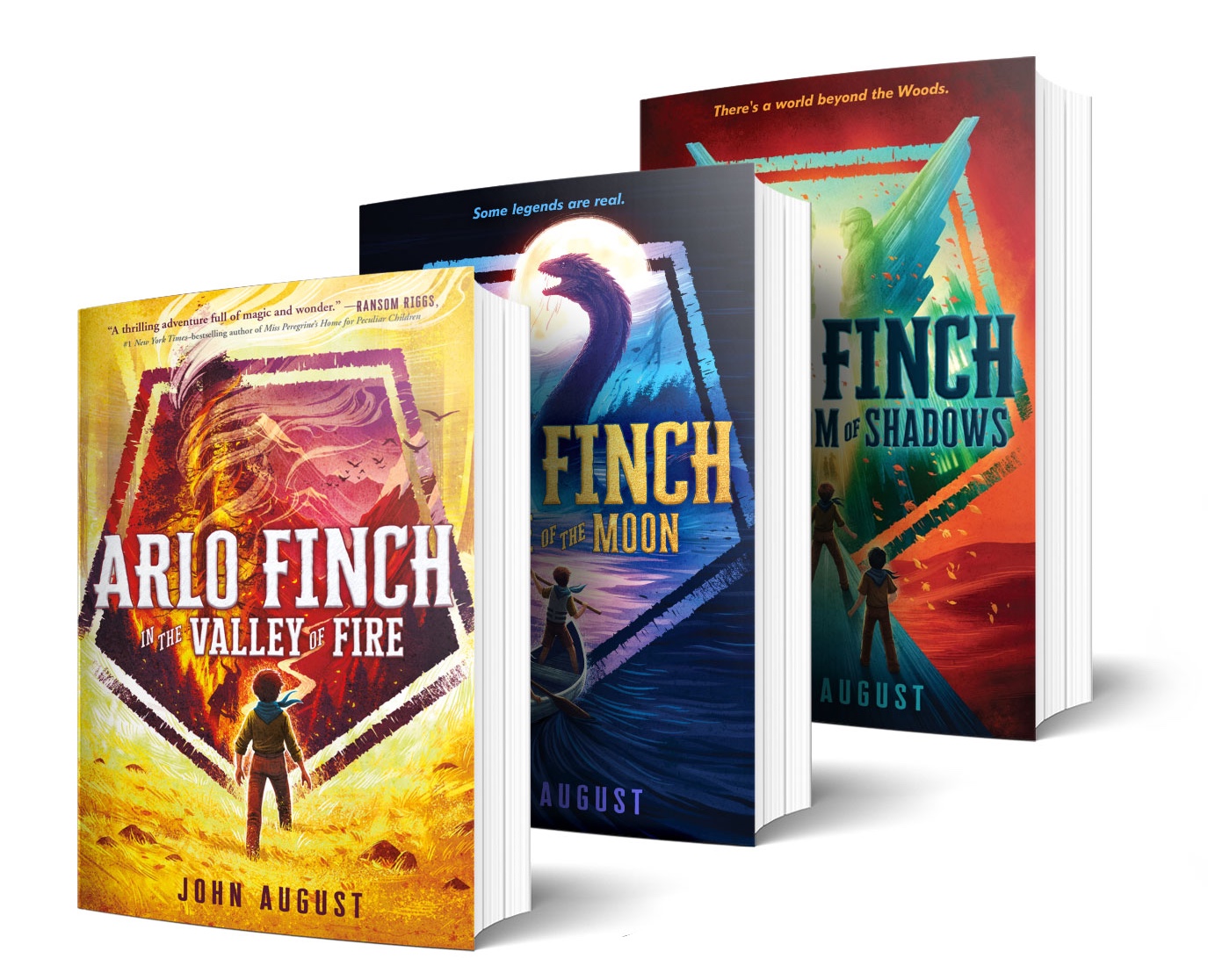

Arlo Finch

Arlo Finch, my middle-grade adventure series. You can get signed books and official t-shirts.

Weekend Read

![]()

Weekend Read is for reading scripts on your phone.

Courier Prime

Courier Prime is designed specifically for screenplays.

Quote-Unquote Apps

Quote-Unquote Apps is my tiny software company that makes these apps.

Contact

For film/TV, I’m repped at UTA.

For books, I’m repped at Writers House.

For press and other inquires, email ask@johnaugust.com