As [announced today](http://www.heatvisionblog.com/2010/06/john-august-reteaming-with-tim-burton-exclusive.html), I’m going to be writing a big movie version of Monsterpocalypse for DreamWorks, based on Matt Wilson’s kaiju-themed giant-monsters-smashing things extravaganza.

As [announced today](http://www.heatvisionblog.com/2010/06/john-august-reteaming-with-tim-burton-exclusive.html), I’m going to be writing a big movie version of Monsterpocalypse for DreamWorks, based on Matt Wilson’s kaiju-themed giant-monsters-smashing things extravaganza.

Wilson’s creation — published by Privateer Press — imagines the modern world under siege by super-sized creatures of every stripe. Giant apes, terrasaurs, planet-eating extraterrestrials? Check, check and check.

Plus robots. C’mon. You need robots.

Many of the elements are still being locked down, so there’s obviously a lot I can’t say about the movie yet: the plot, the players, what the humans are doing in all of this. Will every possible monster be in it? Logic would say no, but I can’t give you a list.

What I can talk about is why the project is getting announced today, while so many others are kept under wraps.

Shouts and whispers

—-

Most of the projects I work on stay under the radar until very close to production. That’s intentional. There are huge advantages to being out of the spotlight.

Particularly with properties that invite media and/or fanboy speculation, there is a real risk of putting the cart before the horse, and having to manage public perception before even finishing the first draft.

That was certainly the case with Charlie’s Angels. From the moment Drew Barrymore signed on, we were constantly battling expectations and fabrications about what a disaster the movie was going to be. Gossips were convinced the actresses would fight, because everyone knows you can’t have [more than one female character](http://johnaugust.com/archives/2010/women-in-film) in a movie. It was an exhausting part of an already difficult project.

Compare that with Big Fish, which over the course of its long gestation had much bigger directors (Spielberg, Burton) but a lot more breathing room. No one said a thing about Big Fish until the trailer. That let us focus on making the movie.

As an extreme example, consider Cloverfield. Secrecy served that movie well.

Another great advantage to keeping a project out of the public eye is the fact that most movies never happen. I’ve got a sizable list of those never-weres, including Tarzan, Shazam, Barbarella, Fantasy Island and Thief of Always. All were announced in the trades. All went through multiple drafts. None of them got made. But they still linger on as “what’s going on with…” questions whenever I do interviews.

So why not play it low and quiet with Monsterpocalypse?

Because there was simply no way to keep a lid on it. As detailed in the article, Monsterpocalypse potentially affects many other tentpole movies at other studios in a way that’s certainly newsworthy. And while I’m hardly the biggest element in this, Monsterpocalypse will take me off the market for a year or so, and make it pretty much impossible for me to direct a movie in the near future.

So an article was going to be written regardless. Announcing the project allowed DreamWorks the chance to have some control over how the story got out. That’s the main and best reason to announce something.

Monsterpocalypse has been the fastest a movie has come together in my career, and I’m ridiculously excited to start writing it. But I’m also ridiculously excited to be writing the other things I’m working on, most of which have been kept very quiet.

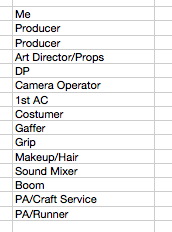

All in, the show cost $25,003. Depending on your perspective, that’s either expensive for a web show or mind-blowingly cheap for television show. We paid for locations, permits and other details a scrappier web show would just ignore. And we had more crew. Some web shows are literally just the actors and a guy holding the camera. We had 15 people. We were more like an indie feature, but without trucks or trailers.

All in, the show cost $25,003. Depending on your perspective, that’s either expensive for a web show or mind-blowingly cheap for television show. We paid for locations, permits and other details a scrappier web show would just ignore. And we had more crew. Some web shows are literally just the actors and a guy holding the camera. We had 15 people. We were more like an indie feature, but without trucks or trailers.