I’ve written about the importance of [a good title](http://johnaugust.com/archives/2005/a-movie-by-any-other-name) before. A great script with a crappy title faces an uphill battle. That’s why I always make sure I have a title I like before I type “FADE IN,” even if I later change my mind. ((I never really had a title for that zombie western, which I should point out, never sold. Readers had [great suggestions](http://johnaugust.com/archives/2005/a-movie-by-any-other-name#comments), though.))

So yes, I’d pay for a great title. Today’s [LA Times article](http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-titles12-2008may12,0,6148790.story) about companies that consult on movie titles sounded promising, until…

> Last summer, Lockhart and Barrie tried to persuade Sony to change the title of “Hancock,” a big-budget action comedy starring Will Smith as an alcoholic superhero known as John Hancock. They told studio executives they thought the current title was vague and pitched alternatives such as “Heroes Never Die,” “Unlikely Hero” and “Less Than Hero.”

There’s spit-balling, and then there’s just spitting. I’d rather have an inscrutable one-word name than any of those crappy alternatives.

I helped out on that movie as it was transitioning from “Tonight, He Comes” to “Tonight He Comes” — the removal of the comma helped soften the double-entrendre. But by the wrap party, it was simply “Hancock,” which serves it well. ((One added advantage of a single-word title is that it requires no translation for international audiences. Except in Germany, where Go is called “Go! Sex, Drugs & Rave’N’Roll.” Shudder.))

By the way, the Josh Friedman who wrote the [LA Times article](http://johnaugust.com/archives/2005/a-movie-by-any-other-name#comments) is not the [Sarah-Connor-Chronicling neighbor](http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0295264/) and [erstwhile blogger](http://hucksblog.blogspot.com/).

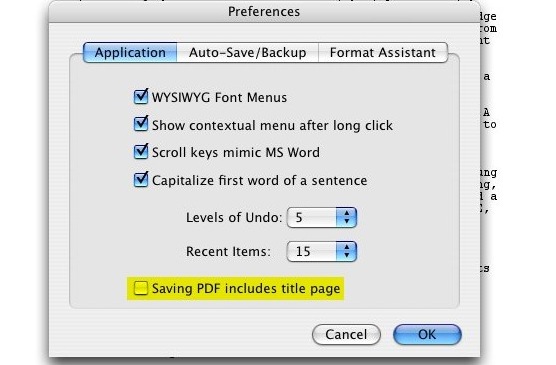

Yes, I’ll admit that I didn’t read the manual with version 7 of Final Draft. But this is a pretty questionable place to put this checkbox. After all, sometimes you’ll want to include the title page, sometimes you won’t. Does it really make sense to have this be an application-wide preference, housed in a panel that has nothing to do with printing, saving or the specific document you’re working on? It’s pretty much the last place I’d think to look for it.

Yes, I’ll admit that I didn’t read the manual with version 7 of Final Draft. But this is a pretty questionable place to put this checkbox. After all, sometimes you’ll want to include the title page, sometimes you won’t. Does it really make sense to have this be an application-wide preference, housed in a panel that has nothing to do with printing, saving or the specific document you’re working on? It’s pretty much the last place I’d think to look for it.