For the past few weeks, I’ve been working on the production notes for The Nines. The document will end up being about 20 pages, detailing the backstory of how the movie got made, from inspiration through editing, along with everyone’s bios. It’s part of the press kit for the film, helping the journalists at Sundance remember who the hell was in the movie they saw three days ago.

Ultimately, we’ll end up formatting the notes in Word or Pages, but for raw text I lean heavily on TextMate, which is what I use for all of the writing for the site. It’s unbelievably powerful, if occasionally maddening.

It’s deliberately, refreshingly bare-bones and retro. When you open a window, it takes over your entire screen, including the menu bar. All you see is the words, complete with a blinking cursor. Perhaps nostalgic for my years writing on an old Atari, I’ve chosen a dark blue background with almost-white 18 pt. Courier. Give me a kneeling chair and a dot-matrix printer and I’m in junior high again.

Other writing applications are picking up this full-screen meme — honestly, it’s hard to figure out why it took so long. Apple’s Pro apps (Final Cut Pro, Aperture) have had no qualms grabbing every available pixel of real estate, although they don’t completely banish the common interface elements. (Except for Shake, which also requires a blood sacrifice to Ba’al.)

The big-screen treatment is the digital equivalent of closing the kitchen door when company comes over: Never mind the mess in the sink, let’s have a nice dinner.

WriteRoom 2.0 is in beta, but there’s nothing spectacularly different or better than plain old 1.0. Either version is worth checking out.

As for the inevitable question: Could I write a script with it?

Yes, no, maybe.

I’ve actually had conversations with two gurus of web markup about creating a simplified screenplay markup that could be imported into “real” screenwriting applications like Final Draft. WriteRoom and its ilk support tabs and external scripts, so it’s conceivable to build a system like ollieman’s screenwriting with TextMate bundle.

But for now, I have an actual paid rewrite to be doing, and it’s a Final Draft job. Sigh.

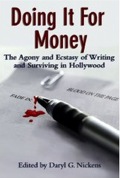

The Writers Guild Foundation has a new book out,

The Writers Guild Foundation has a new book out,