Daniel Wallace, author of the novel Big Fish, has opened his own website with information about his books, illustrations and screenplays. It’s great. In fact, it has me sick with envy. Daniel even has links through which you can buy his books from Amazon — which you should, because that way he’ll get an extra couple percent in addition to royalties.  And if that gets him to write more, well, you’ve done your part to make the world better.

And if that gets him to write more, well, you’ve done your part to make the world better.

Projects

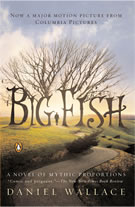

New Big Fish paperback

Penguin is issuing a special paperback version of Daniel Wallace’s “Big Fish” with the new cover artwork. (You can see the bigger version of it here.) The cover is essentially the same as the upcoming one-sheet poster.

How long to write a script

How long did it take to write GO? How long does it take to

write a finished script? Do you work at an office day in, day out, or is it

different?

–Floris

GO took about two years to write, but it was an unusual case in that I wrote

it as a short film, then let it sit around for a long time before I did the

full version. My active work time on the script was probably about four months,

which is not a bad estimate for most of the things I’ve worked on.

Some things have had to go faster out of necessity. I wrote the first draft

of CHARLIE’S ANGELS in three weeks, because that was all the time I had available

between commitments. (I later went back and did another two months of work

on it, right before production.)

Currently, I work out of an office in my home. I have an assistant who works

from 9 to 6, which is what I consider my "working" hours, but truthfully

my life is more like college. Sometimes you can screw around during the day,

and sometimes you have to pull all-nighters to get work done.

More copyrights and changes

How important is it to have your screenplay registered through the US copyright

office? And if you do get it registered, what happens if you add more scenes

later on?

–Ben Goldblatt

Officially, yes, you should copyright your screenplay (with the little "c" symbol,

name and date) on the title page, and then send it in to the U.S. office, a

procedure you can probably find on-line. And if you make major revisions, you

should probably re-register the whole thing.

Unofficially, nobody does this. Sometimes you’ll see the copyright symbol

on a script, but most of the time you won’t. And none of my writer friends

regularly send in their work to be "officially" copyrighted.

Although it’s not really the same thing, most writers I know do register their

scripts with the Writer’s Guild in Los Angeles, a painless procedure

that can occasionally help if your idea is blatantly stolen. But the truth

is that "someone might steal my idea" is more often the fear of an

aspiring writer who’s never put pen to paper than of a working screenwriter.

I’m ragging on it, but sometimes copyright becomes very important. For instance,

when a script is sold, what the studio is really buying is the copyright. (Or

the right to copyright.) I’m currently adapting BARBARELLA, a project to which

four different studios were claiming copyright. It’s taken the legal teams

more than a year to sort out who really owns what, since two of the original

French comic books were already made into a movie.

The process of determining copyright is called "clearing the chain of

title," and it’s often used as the answer to "Why haven’t they paid

me my money yet?"