I wrote both [Arlo Finch][arlo] novels entirely in beta versions of Highland 2.

It’s either brave or foolish to trust your essential daily work to unfinished software. But in three years of writing in Highland 2, I never lost a word. What’s more, the decision to write Arlo Finch in Highland 2 influenced both the books and the app itself.

In this post, I want to talk through my workflow for writing Arlo in Highland 2. The app is [now available on the Mac App Store][mas] as a free download, so you can work along with me if you’d like.

You can also find the first six chapters of Arlo Finch in .highland on our [website][h2]. (And of course, Arlo Finch in the Valley of Fire is available pretty much [wherever books are sold][arlo].)

## A chapter at a time

As a screenwriter, I tend to start working on a script by handwriting individual scenes. This keeps me from going back and editing too much, too soon. I try to get at least a third of it handwritten before I switch to the keyboard and begin assembling the script.

With books, I’ve found writing by hand simply isn’t practical. There are just too many words. If I’d stuck with my screenwriting technique, I’d still be writing the first book.

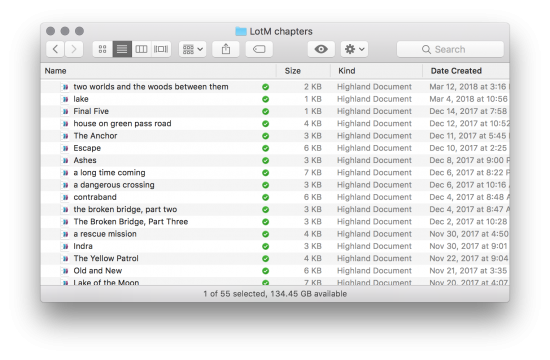

But the basic idea of working in small chunks rather than a massive file remains sound. For Arlo Finch, I wrote each chapter as a separate file. This helped enormously.

For starters, it helped me keep my chapter lengths relatively consistent. For middle grade fantasy fiction, you want them to be between 1,000 to 2,000 words. That’s long enough to propel the story forward, but not too long for bedside chapter-a-night reading. If I’d written the book as one giant file, it would be harder to know how long each individual chapter was.

Keeping chapters as separate files also kept me from going back and endlessly tweaking earlier chapters. I’ve found it’s important to start the day’s work as the next thing you’re writing, not second-guessing what you wrote before. It’s fine to run your pen through yesterday’s work to get up to speed, but the further back you go, the less forward progress you’re likely to make.

This basic idea of writing a book with separate files for each chapter could be done using any app. But Highland 2 makes it much easier thanks to a little bit of magic.

In addition to my files for individual chapters, I made a new document called Arlo Assembly. ((In movies, an assembly is the film editor’s first pass at putting all the scenes in order.)) This file isn’t for writing anything, but rather links to all the individual chapters, which I add by simply dragging them in from the Finder.

—

When you drag a text file into a Highland 2 document, it creates an {{INCLUDE}}. It’s not importing the text itself, but rather a secure bookmark to the original file. Then, whenever you preview the document, Highland 2 finds the original file and includes that text.

Here’s why using INCLUDE is so useful.

1. **It’s not creating a copy of the text.** If I {{INCLUDE}} a chapter, then make a change in the original file, that change will show up the next time I preview the assembly. The original chapter file is still the “real” version.

2. **You can quickly get an overview.** How long is the book so far? It can be hard to tell. But it’s easy to check the assembly to see that you’ve spent 60 pages away from a major character.

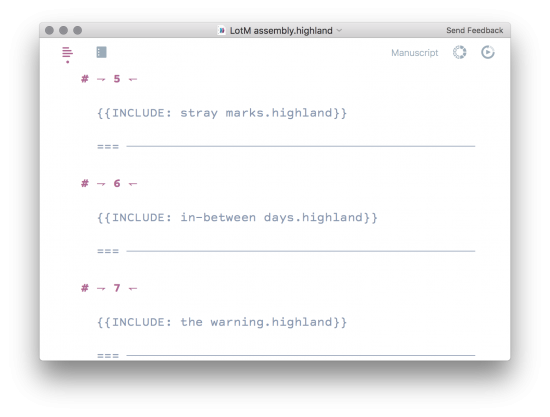

3. **You can wait to number the chapters until you’re finished.** For book one, I named and numbered chapters in their individual files, which made it a hassle when I decided to move one chapter earlier. So for book two, I numbered the chapters only in the assembly. Here’s what that looked like:

The # are headers for the page numbers, while === represents a forced page break.

Once I had all the chapters written and included, I used File > Assemble… to generate a new document that had all the text copied in. From that point forward, this was the “real” version of the book.

## Just the words

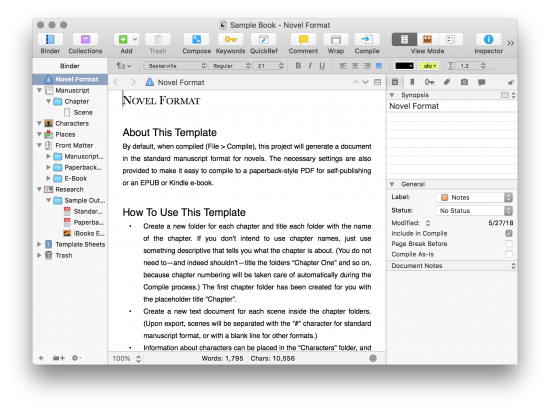

Other apps can do similar things with small files organized as larger projects. Scrivener is probably the best-known of these.

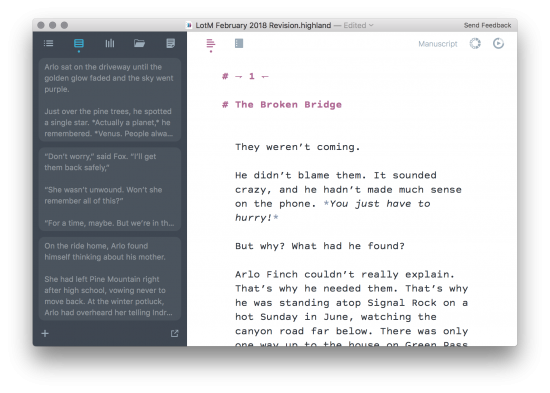

Here’s the default view in Scrivener:

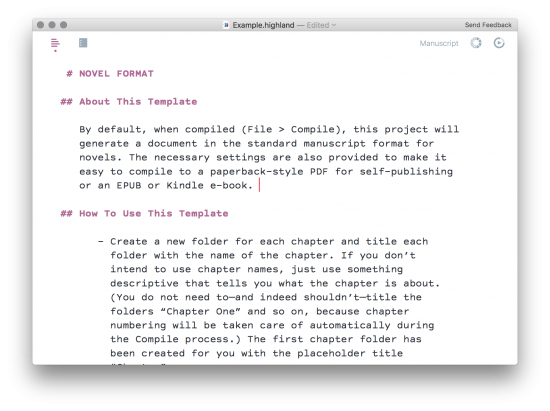

Here’s the equivalent view of the same text in Highland 2:

Which would you rather write in?

To be fair, some novelists love Scrivener, and it can do some things that Highland 2 cannot. It has a cork board and key words and dozens of other tools of questionable utility. Like a traditional word processor, Scrivener lets you set each sentence — each individual character — in its own font and size.

But to me, Scrivener feels like piloting the space shuttle to the grocery store. It’s way too much app for daily writing, and makes the job of a novelist seem technical rather than intuitive. I think Scrivener’s bells and whistles are counterproductive distractions.

## Sprinting a marathon

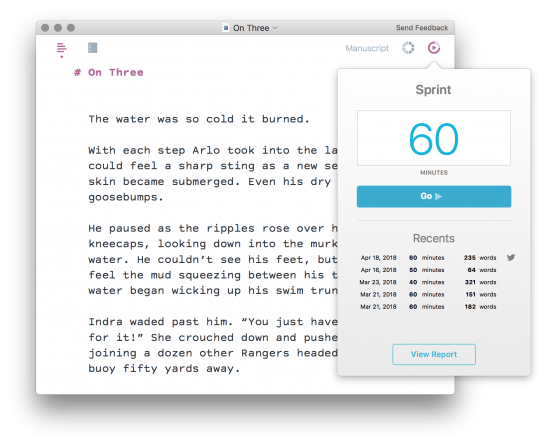

Avoiding distraction was the motivation behind one of my favorite features in Highland 2: Sprints.

I like to work in 60 minute installments. That is, I’ll decide that for next 60 minutes I’m writing and doing nothing else. No Twitter, no phone, no looking things up online. Then when the time is up, I’ll step away and do something else.

I’ll often announce when I’m about to start one of these #writesprints so others can join me.

Highland 2’s new Sprint tool makes these dead simple to do.

Two or three sprints a day generally keep me on track for 1,000 words per day. I’d estimate that I wrote at least 70 percent of the second Arlo Finch in sprint mode.

## The right template

Like screenplays, manuscripts have standardized formatting, with lines double-spaced and paragraphs indented. Many novelists simply type in this layout in Word, but it’s not particularly efficient. You can’t see multiple paragraphs at once, which makes it hard to get a sense of the flow. *Wait, did I say “suddenly” ten lines back?*

In Highland, you’re writing single-space in regular non-indended chunks, just like an email. Only when you preview do you see the manuscript formatting, thanks to the new Manuscript template. You’ve got your choice of Courier Prime or Times. That’s it. That’s all you need.

## The Bin

Highland 2’s final innovation is one of its most helpful, and I used it extensively for Arlo Finch, particularly after I had assembled all the chapters into one big file.

A thing writers face all the time is there are bits of text you need to cut, but you also need to hold onto. It could be a paragraph describing a location, or a chunk of dialogue that needs to find a new home.

What most writers do with these bits of text is to save them in a new scratch file. In Highland 2, you simply drag them to the sidebar in a new location we call the Bin. ((The Bin is also a film editing term. It’s where you hold all the piece of film you’re working with.))

If I need any of those pieces again, I can just drag them back in. I can also export the Bin as its own file if necessary.

## Speed matters

Once I’d finished my first draft, I submitted it to editor Connie Hsu as a PDF. We went through two rounds of notes, then it was time for the copy edit.

Copy editing is the process books go through where proofreaders and production editors carefully check the manuscript for mistakes, everything from typos to grammar goofs to logic errors. It’s painstaking work, and is almost always done in Microsoft Word using its Track Changes feature.

So for both books, at this stage I had to switch away from Highland. I exported an RTF and imported it into Word.

And groaned in frustration. A lot.

Microsoft Word is often mentioned as bloatware, with a thousand toolbars and obscure features. I used to think the criticism was mostly about its user interface, but the truth is that at least on the Mac, Word is glacially slow when handling long documents.

In a moment of pique, I made a video to compare just how slow it is compared to Highland 2.

—

But I’m lucky. Through the whole process of writing Arlo Finch, I’ve had to spend less than three weeks in Word, while I’ve spent three years in Highland 2. Using an app so tailored to my process is a pleasure.

Yes, the writing itself is still difficult. Trying to make words obey your intentions is always a struggle. But with Highland 2, I’m wrestling with the work rather than than app.

In the end, any application is simply a tool. After all, Leo Tolstoy [wrote War and Peace by hand][twitter] and George R.R. Martin sticks with his [WordStar 4.0][martin]. I’m sure I could have written Arlo some other way. But I didn’t. I used Highland 2 and I loved it.

[twitter]: https://twitter.com/lit_books/status/466949240020021249

[martin]: http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2014/05/14/george_r_r_martin_writes_on_dos_based_wordstar_4_0_software_from_the_1980s.html

[arlo]: http://johnaugust.com/arlo-finch

[mas]: https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/highland-2/id1171820258

[h2]: https://quoteunquoteapps.com/highland-2/