This week, the WGA announced an [upcoming referendum](https://secure.wga.org/uploadedfiles/the-guild/elections/scrc_cover_letter.pdf) on a proposal to create an “Additional Literary Material” end credit for feature films.

I was part of the committee that drafted the proposal, and took the lead in writing up the [exhaustive explainer and FAQ](https://www.wga.org/uploadedfiles/the-guild/elections/screen_credits_explainer.pdf). ((I beg you, please read the explainer. We really tried to answer every question you might ask.))

Outside of my role on the committee, I want to talk through how and why my thinking about end credits has evolved over my 20+ years as a screenwriter, and why I think members should vote yes on the proposal.

## The way it’s always been

Going back decades, the WGA has had a process for determining who gets credit for writing on a movie. These are the familiar “by” credits: written by, screenplay by, story by, etc.

These credits denote authorship. Whether a film uses opening titles or end titles, the writing credit always comes right next to the director. They answer the question, “Who wrote that?”

But they don’t tell the whole story. In many cases, other writers worked on the project. If they didn’t meet the threshold for receiving this “by” credit, all record of their employment is erased.

That’s unique to the film industry. In television, members of a writing staff receive an employment credit (e.g. staff writer, story editor) in addition to a writing credit on episodes they write.

The idea of listing every writer who worked on a movie is not new. It’s always seemed absurd that a catering truck driver who worked one day on a film has their name in the credits, while a screenwriter who spent a year on the project and wrote major scenes goes uncredited.

And yet! **Screenwriters are not drivers.** Our work is fundamentally different. Authorship means something, both for the individual project and for the status of screenwriters as a profession. That’s why in the case of projects with multiple writers, the Guild has an arbitration process to determine the official writer(s) of the script.

*But what about listing the other writers in the end credits, away from the “by” credits?*

For at least 20 years, I’ve been able to argue both sides of the end credits question. Pro: Listing all the writers better reflects the reality of who worked on a movie. Con: Listing all the writers undercuts the purpose of the WGA determining credits in the first place. Like a high school debater, I knew the arguments and was ready to engage on either side of the debate.

I didn’t want to pick a side — but of course, I *was* picking a side. When the status quo is no end credits, doing nothing means perpetuating the current system.

During my year working on the committee, a few things got me to change my mind.

## Recognizing survivorship bias

I’ve received credit on films I wrote, and lost credits I thought I deserved. On the whole, it’s worked out. My resume looks pretty full, particularly in those crucial early years of my career *(Go, Charlie’s Angels, Big Fish)*.

Even on movies where I didn’t get credit, “the town” knew I did the work. I kept getting hired and increasing my quote.

Talking with many of my screenwriting peers — writers in their 40s and 50s — that’s largely been their experience as well. It’s not surprising given the phenomenon of [survivorship bias](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Survivorship_bias). If you’re only looking at the screenwriters who made it, you’re going to assume the system is working well.

But what about the screenwriters who aren’t getting credit? What’s happening to them?

Talking with members currently at the early stages of their screenwriting careers, they describe a very different universe than I experienced, one with month-long writers rooms, simultaneous drafts and cultural sensitivity passes. Their missing credits are not because of bad luck, but rather because of an environment that makes it much less likely they could ever receive credit.

That sense that “the town” knows who really wrote something? There is no town anymore. Instead of six studios, there are countless production entities, many of them not based in LA. Netflix is so giant that one team has no idea what another team is making.

In 2021, when a screenwriter receives no credit on a film, it truly is like they never worked on it.

When thinking about missing screenwriting credits, I mistakenly assumed that my experience in the early 2000s matched screenwriters’ experiences today. It doesn’t.

## Comparing imagined harm to actual harm

Most of the status quo arguments I’ve heard for the past twenty years foretell grave consequences if additional writers were listed in the end credits. Some common predictions:

– It will devalue the worth of the “by” credits

– Studios or producers will hire friends just to get their names in the end credits

– It will hurt newer writers if a big-name writer showed up in the end credits

All I can say is, maybe! We’re screenwriters; it’s our job to imagine scenarios.

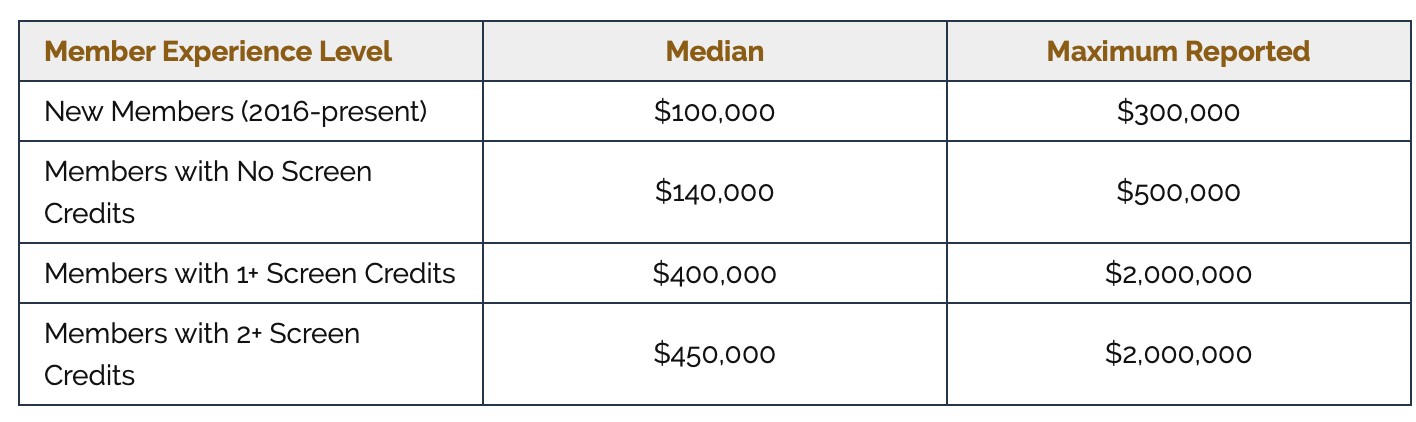

But it’s also important to check the facts. Earlier this year, the WGA [examined over a thousand feature contracts](https://www.wga.org/members/employment-resources/writers-deal-hub/screen-compensation-guide) to look at trends in compensation. One finding: credit matters a lot.

The median guaranteed payment for a screenwriter with no credits was $140,000. The median guaranteed payment for a screenwriter with one credit was $400,000.

**A single feature credit more than doubled a screenwriter’s pay.**

Would receiving an “Additional Literary Material” credit result in the same bump? Likely not to the same degree. *But it would show that a screenwriter worked on a film that got made.* I strongly believe that’s going to be worth real dollars to that writer. In my discussions with newer writers, agents and executives, most of them agree.

This impacts quite a few writers. In 2020, 185 participating writers wrote on produced features for which they ultimately received no credit.

I should also note here the Guild’s Inclusion & Equity Group’s concern that the status quo disproportionately affects women and writers of color, for whom these resume gaps can be a substantial barrier to future employment.

When comparing the theoretical harms of end credits to the actual harms of doing nothing, I think it’s better to solve the real problems members are having.

## Finding a middle path

Even after acknowledging my survivorship bias and the actual harms screenwriters are facing, I wouldn’t have supported many of the more aggressive proposed changes to the credit system. For example, I don’t believe in changing the thresholds for the “by” credits, expanding the definition to include non-writing roundtable participants, or having all participating writers share in the residuals pool.

Instead, what the committee came up with after a year of sometimes-heated debate was a proposal that narrowly addresses the “resume problem” of missing employment credits without changing anything about the traditional writing credits. The result closely mirrors the system used in television for decades, where writers are credited for both their employment and their authorship.

The term “Additional Literary Material” is incredibly dull, but it’s also accurate. It reflects the reality that the people listed wrote material for the film without passing any judgement. It clearly delineates actual writing — words on paper — from participating in a roundtable.

Rather than diluting the authorship credit of the “by” writers, I’d argue the “Additional Literary Material” credit reinforces it. By definition, any writer listed it this block did not meet the thresholds for receiving “by” credit. (And if a writer chooses not to be included in “Additional Literary Material,” it’s their decision alone.)

In summary, I changed my mind on end credits because I realized I wasn’t looking at the reality experienced by many screenwriters in 2021. This proposal addresses a specific problem with minimal disruption to long-established screen credit processes.

Voting on the referendum begins November 2nd. I urge you to vote yes.

—

Supporters of the proposal are gathering signatures for a Pro statement. You can read it [here](https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hgg4aNTa5pY-eN1nFyb9X-0rc-dBj8KRTsVzOApdHBk/edit).

WGA members can sign on by sending an email to yesonendcredits@gmail.com with the subject line “PLEASE ADD MY NAME TO THE CREDITS PRO STATEMENT. Please include your name and preferred email address.