I’ve written about residuals many times, and it’s a frequent topic of conversation on Scriptnotes.

But as a quick refresher, let’s go to the definition:

RESIDUALS

Payments made to a film or television writer when their work is sold to another venue, such as a feature film sold on DVD, or a network television episode shown in syndication. These fees are percentages negotiated and collected on behalf of writers by the Writers Guild of America.

The most important thing to remember is that residuals only happen after the the initial run/venue. So, for a feature film, you don’t get residuals on the money it makes in theaters. ((Or, weirdly, airplanes.)) For a TV series, you don’t get residuals the first time it airs on television. When an episode runs in syndication, or a movie is sold on DVD, that’s what counts.

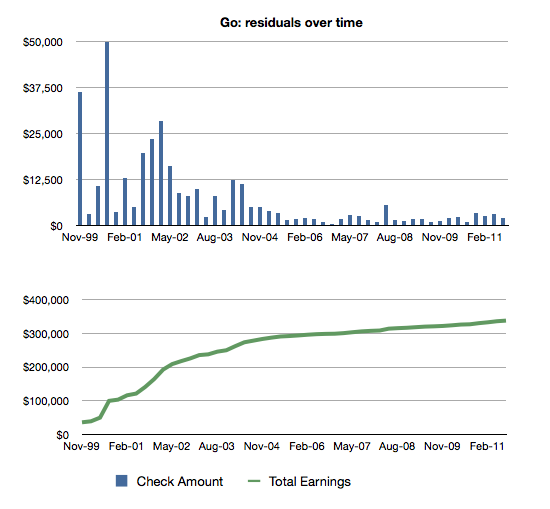

I’m mostly a feature writer, so that’s been the bulk of my personal experience with residuals. For example, here’s a look at the residuals I’ve earned from Go from 1999 to 2011.

For feature writers, residuals are an important way of keeping money coming in the door in the years between getting movies made. Without residuals, it would be difficult for many feature writers to stay full-time writers.

As Craig and I often discuss on the podcast, most WGA members — including a lot of elected board members — don’t have firsthand experience with feature issues, including residuals. So I wanted to highlight some numbers about how feature residuals have changed over the years.

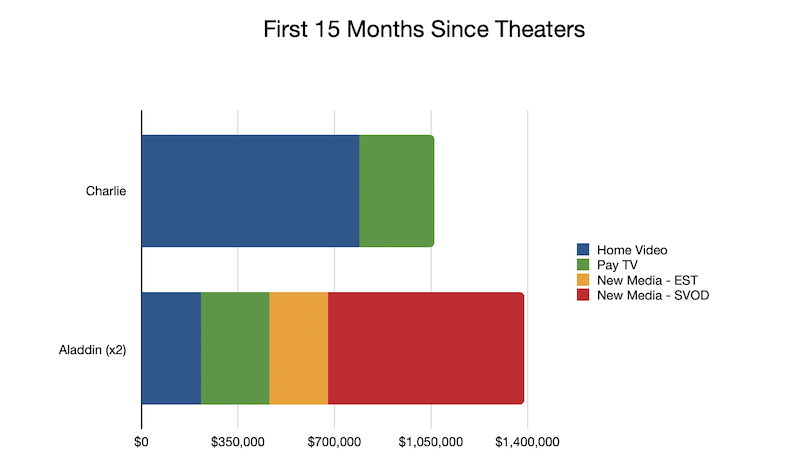

I’m comparing two movies I wrote: 2005’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and 2019’s Aladdin. I picked them because they’re very similar movies — four-quadrant family films that made a lot at the box office. ((Inflation adjusting for 2019 dollars would put Charlie at $270M domestic and $621M worldwide.))

| Title | Domestic Box Office | Worldwide Box Office |

|---|---|---|

| Aladdin | $355,559,216 | $1,050,693,953 |

| Charlie | $206,459,076 | $474,968,763 |

As the writer, I know exactly how much these films paid out in WGA residuals. ((For Aladdin, the residuals are divided between me and the co-writer, so I’ve doubled them here.)) Here’s what each film generated in its first 15 months after concluding its theatrical release:

| Title | Home Video | Pay TV | New Media – EST | New Media – SVOD | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlie | $789,439 | $272,283 | $0 | $0 | $837,146 |

| Aladdin | $216,484 | $247,324 | $212,387 | $712,104 | $1,388,299 |

Home video is what you think: DVDs, or VHS back in the day.

Pay TV is cable, like HBO.

New Media EST means “electronic sell-through,” like iTunes and such. There are rates for both purchase and rental.

New Media SVOD stands for “subscription video on demand.” Think Netflix or Disney+.

Here’s what this looks like in a bar chart:

A few takeaways:

- Residuals are still a thing. Aladdin has kicked off $1.3 million in WGA residuals so far.

- The home video market is much, much smaller than it used to be. My hunch is that Aladdin sold better on home video than many non-family movies, so for many titles, their home video percentage is probably even smaller.

- SVOD is huge, and largely makes up for the decline in home video.

As consumers, it’s obvious that SVOD is the future. We’re not buying many DVDs. We’re cancelling our cable. And while we might still rent a movie, we’re more likely to see what’s on Netflix.

As writers, we should be watching SVOD residuals very closely. They’re not built on the same foundations as our other sources, and could quickly collapse.

Unlike home video or EST, SVOD residuals aren’t based on how many times someone watches our work. The streamers are loathe to share any information about viewership. So instead, SVOD residuals are treated more like pay TV and broadcast residuals in that writers are paid a percentage of the license fee. Basically, we get a cut of whatever the studio charges the streamer.

That works great when Warners charges Neflix $100 million for Friends. But how do we make sure Disney isn’t selling Aladdin to Disney+ for less than it’s really worth?

One way to look at self-dealing is to bring in comps. If you can show that a streamer paid $5M for a three-year license to a similar film, it’s hard to argue that it’s “really” worth only $1M. But that only works when there really is a market. Every studio basically has its own streaming service, so it’s increasingly difficult to show any comparative prices.

An even bigger concern is what happens when these movies debut on the streamers. Remember: residuals are paid only on money earned outside of the initial venue. If Aladdin had debuted on Disney+ rather than in theaters, would it have generated residuals at all? I suspect that’s an open question, one that feels especially relevant as more movies are being pulled from theaters during the pandemic.

Craig and I talk about these issues on episode 472 of Scriptnotes.