Give Horace Dediu a bunch of Hollywood data and he’ll make [some great charts](http://www.asymco.com/2012/02/07/hollywood-by-the-numbers/) that test your hunches.

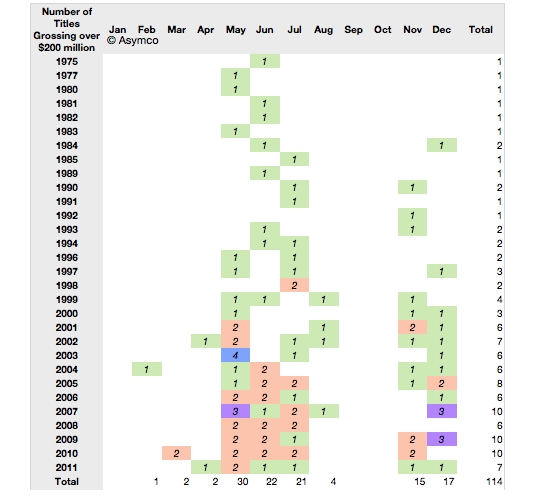

For example, it’s very unlikely to have a $200 million blockbuster outside the summer or Christmas windows:

(That outlier from 2004 is [The Passion of the Christ](http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=passionofthechrist.htm).)

Deidu asks a question I’d never considered: How feasible is it for an outside company to become a major distributor?

> The top five [studios] were earning 64% of revenues in 1975 and the top five were earning 60% in 2011. One of the top five from 1975 is no longer in the running this year (MGM) and one new major was added (Buena Vista, owned by Disney).

> There has been one other notable change: Columbia was acquired by Sony but stayed out of the top 5. Beside Disney there is one new significant entrant in Dreamworks gaining share in the last decade.

> But the prevailing impression from the data is that the incumbents remained as such during the last four decades. There are many small studios but they have not “disrupted” the market by shifting significant revenues out of the hands of the majors.

The same big studios have been dominating the business for *forty years.* That’s remarkable stability for an industry that feels so tumultuous.

Dediu’s [whole analysis](http://www.asymco.com/2012/02/07/hollywood-by-the-numbers/) is worth a look. Or a semester’s study.