“Paul from LA” wrote in with [this link](http://babynamewizard.com/voyager) to a site I kind of remember using when we were picking a name for my daughter. It lets you type in any first name and graphs how popular it has been (in the U.S.) over the past 130 years. What’s less obvious is that if you hover over the graph at any point, it can show you a name’s rank in that year.

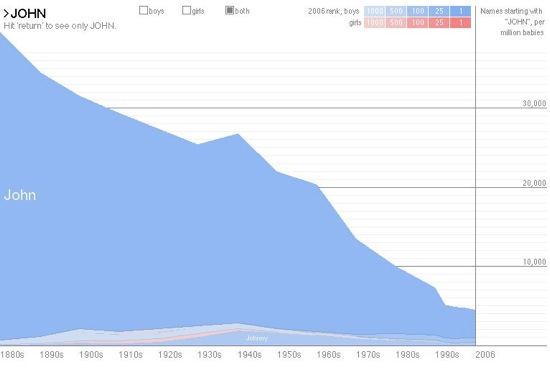

For example, here’s John, which has fallen from #1 to #20.

[ ](http://babynamewizard.com/voyager#prefix=JOHN&ms=false&sw=m&exact=true)

](http://babynamewizard.com/voyager#prefix=JOHN&ms=false&sw=m&exact=true)

It’s worth a bit of time-wasting to see how names come and go.

![[Scene Challenge]](http://johnaugust.com/Assets/scene_challenge.png)