As a screenwriter, most of my writing takes place in the third-person present tense. Movie characters run, shoot and misbehave within a small subset of the words, senses and actions that other literary characters take for granted. We never know what Indiana Jones is thinking, unless he tells us. We don’t know what a Wookie smells like, unless another character mentions it.

As a screenwriter, most of my writing takes place in the third-person present tense. Movie characters run, shoot and misbehave within a small subset of the words, senses and actions that other literary characters take for granted. We never know what Indiana Jones is thinking, unless he tells us. We don’t know what a Wookie smells like, unless another character mentions it.

Don’t get me wrong: I love screenwriting. But it’s limited.

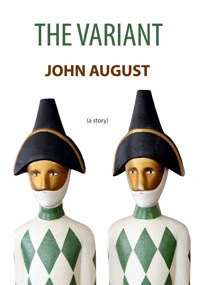

So when a friend asked me to write a short story, I jumped at the chance. The thing I wrote, The Variant, was and maybe still is supposed to be part of an anthology of short stories written by well-known screenwriters. It falls in that loose genre of spy-fi which encompasses both The Prisoner and Jorge Luis Borges.

After leaving it to sit on the shelf a few months, I considered sending the story out to the usual magazines that publish short fiction. But it’s not really a New Yorker story. It probably belongs in a sci-fi quarterly, one that I would never buy unless specifically instructed. And I would have a hard time nudging all my friends to drop five dollars on a magazine they had never heard of.

So, in the spirit of iPhone apps and [Jonathan Coulton](http://www.jonathancoulton.com/) tracks, ((I discovered the delivery system (E-Junkie) through Coulton.)) I’m releasing it myself for 99 cents. You can get it as a pretty .pdf, or on your Kindle through Amazon. ((And if you live in the U.S, keep in mind that every iPhone can now read Kindle books with the Kindle app.))

You can find all these options here: [johnagust.com/variant](http:/johnaugust.com/variant)

This is all an experiment, obviously. I’m lucky to have a career where it doesn’t matter if this generates $15 or $1,500. But I’m curious whether this is a feasible model for a writer. In the next few weeks, I’ll be posting the results.

I’m well aware that there are going to be some people who simply can’t pay 99 cents for something online. And while I can’t anticipate every scenario, I’ve set up an email account (sales@johnaugust.com) to figure out solutions.