The original post for this episode can be found [here](http://johnaugust.com/2018/netflix-killed-the-video-store).

**John August:** Hello and welcome. My name is John August and this is Episode 364 of Scriptnotes, a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters.

Today Craig is off in Chernobyl land in a hotel that from his descriptions sounds like Eastern Europe’s equivalent of the Overlook, so he is my Daniel Lloyd, I am his Dick Halloran, except instead of The Shining we have spotty text messaging. Assuming he escapes the hedge maze he will be back next week.

In the meantime, I am lucky to have a special guest. Kate Hagen is Director of Community, is that correct?

**Kate Hagen:** That’s right, yeah.

**John:** At the Black List. I want to talk to her about what that means, but mostly I want to talk to her about her blog post about the state of home video, video stores, and the many movies that are weirdly unavailable. Kate, welcome.

**Kate:** Thanks so much for having me, John. This is a pleasure to be able to be on the much-loved Scriptnotes.

**John:** And so I’d seen your blog post, the one that kicked this all off about the last great video store months ago. And I had always bookmarked it. It was going to be a One Cool Thing, but it felt too big to be a One Cool Thing because I actually wanted to talk about it. And it sort of slipped down in my feed of stuff to discuss. And in the past two weeks I had trouble trying to find a copy of The Flamingo Kid, and it all surfaced up again. So, I was encountering what you had encountered. What was the movie that you were trying to look for?

**Kate:** I was trying to look for a movie called Fresh Horses, which is most notable for being the only reteaming of Andrew McCarthy and Mollie Ringwald after Pretty in Pink. It’s not a good movie, it’s just one of those ‘80s curiosities that I was like, “Oh, I’d like to see this again.” And I started looking for it one night and the only version I could find was on like a very illegal website where it was dubbed in Polish. And I was like well that’s pretty nuts. This movie is 30 years old. Ben Stiller and Viggo Mortensen are also in it, so it’s not like a nobodies’ movie. And the only way you can get Fresh Horses currently is in one of those six-movie ‘80s collections on Amazon, which is a bummer, because then it’s just like a crappy version of the movie.

**John:** Cool. So let’s try to figure out and solve all the problems of missing home videos in the next hour.

**Kate:** I think we can do it.

**John:** But we’ll start with simpler things which you can explain what you actually do at the Black List.

**Kate:** Yeah. So my fun answer for this is I am like the ultimate Internet team for the Black List. So I’m kind of the online mom of the Black List. I make sure all of our online community is healthy and getting along with each other. That includes everything from doing all of our social media, to editing and curating our blog, to overseeing customer support. I run point on all of our site partnerships. So, Franklin likes to put it that Megan and I – Megan is our director of events – and she kind of handles everything that is an in-person interaction and I handle everything that’s an online interaction.

**John:** So Franklin Leonard launched the Black List as a site shortly after one of the Austin Film Festival appearances. So he came on the show, on a live show, to talk about this plan he had for the Black List and it’s been fascinating to watch it grow into this big thing that it is right now.

So, you are part of a small team, and so as people are submitting scripts that they want to show up on the site for coverage and for other things for professionals to look at them, you are part of the team that interacts with those folks?

**Kate:** Yeah. So like day-to-day I’m just keeping an eye on everything that’s coming through the website in terms of evaluations, if there are any issues with any scripts or anything. I’m kind of just the keeper of all of that stuff. And, you know, making sure people can opt into partnerships, all that kind of good stuff.

**John:** Now at this point are you still reading scripts that come in, or are your days as a reader behind you?

**Kate:** My days as a reader are behind me. I was a reader – it was my full-time gig for about eight months, but I was doing freelance for about a year and a half. And I covered about 500 scripts in that time. Yeah, and there are definitely days when I miss being a reader. I mean, there are other days where I’m super glad I don’t have to do that anymore. But like friends will reach out to give notes on their scripts and I’m like, “Oh, I really like doing this,” the kind of page notes where you have a good relationship with someone and you can be like this is not working and they’re not going to get mad at you, as opposed to just sending coverage off into the void.

**John:** Weirdly over the course of all these episodes of Scriptnotes I don’t think we’ve talked that much about the job of a reader, sort of what it’s like to be a reader. So, my first jobs in Hollywood were as a reader. I started as a reader covering scripts for Prelude Pictures, which doesn’t exist anymore. It was this tiny little company based over at Paramount. And every week I’d go in, they’d give me two scripts. I would write up my coverage on these two scripts, then come back in, deliver those, and pick up new scripts. This was back in the day when there weren’t PDFs, so you were actually physically picking up scripts and reading them and writing up your coverage, and printing them out and sending them back in.

I assume this is all happening digitally these days?

**Kate:** Yeah. It’s all happening digitally at least as far as the Black List is concerned. People just upload their scripts to the site. The readers are then able to access those scripts, and they provide an evaluation. And our coverage is a little bit different than traditional coverage. It’s meant to be kind of a high level notes for the writer. It’s not getting into like page-by-page details some of the time. Although some readers choose to do that. It’s more focused on what’s working in the script, what’s not working in the script, and what the likely audience for that might be.

**John:** Yeah. It’s a very different relationship to the writer than coverage traditionally is. Because coverage classically what I was doing for Prelude, then I was a reader at TriStar, you’re really just a gatekeeper in that function. Basically a script comes in, the executive doesn’t have time to read it, so you are basically writing a book report, a summary of what happens in the script and your overall reaction to the script. Sometimes it’s a page and a half of summary and then one page of comments talking through characters, plot, sort of overall impressions of “Is this a good writer?” a recommendation – like consider this script, consider this writer, consider both. And generally the answer is consider neither for most–

**Kate:** Yeah.

**John:** That’s the function is basically to say no to everything.

**Kate:** Yeah. It’s so funny. So before I was reading for the Black List I was reading freelance for Bold Films. And I read probably I’d say about 100 scripts for them in that period of time. And the only two things I ever recommended were Arrival and Dark Places, the script for that. But, yeah, I think most people don’t realize that as a reader and a gatekeeper you need to be passing on 95% of stuff. It’s very rare that you get anything that kind of emerges from the pile.

But I would have moments, too, where like it would be a very talented writer who was given like not a great book to adapt or something. And it was nice to be able to be like, “Hey, this writer is really great, even if this material is not working.” And I do think that’s something that like we don’t focus on enough in evaluating scripts. It’s all about the script itself, and obviously you have to execute a script, but it would be nice sometimes if we directed some of that love back to the writer if they’re doing a good job.

**John:** Definitely. Sometimes the function of a reader is you’re looking for a specific thing that this company can make, and so if something doesn’t fall into the purview of what this company would make you’re going to pass on it because you don’t want to waste the executive’s time reading this thing that they can’t actually do. But along the way you sometimes will read good writing and in my time reading for TriStar I read 200 scripts. I still have a list of all that coverage. And none of the things I read ended up getting made. Two of the things I ended up recommending I sort of got called to the mat for wasting people’s time for recommending them. It’s so frustrating.

**Kate:** And taste is so crazy. You know, there’s a sort of consensus I feel like in terms of what’s good in Hollywood, but then you get a lot of outliers and it depends on people’s bosses and all that kind of good stuff. And like you were saying in terms of what a given company can make within a calendar year, or couple of calendar years. Yeah, so it’s a tricky gig.

I think a lot of screenwriters have this kind of attitude about readers that like they’re trying to pull one over on them. And it’s like, no guys, we just want to read good scripts. Like that’s all we ever want to do. And I’m sorry that most scripts are not good. It’s a bummer. I would love to recommend scripts all the time.

**John:** And I think another thing people don’t understand is that most readers are writers, or at least a sizable portion of readers are actually screenwriters themselves. And it’s a very classic first job in Hollywood is to be one of those readers. If someone wants to be a reader, I mean, the Black List is a sort of a special case, but in general how are people getting hired as readers these days?

**Kate:** Yeah, I mean, this is a tricky question. I have a number of friends who are still reading and I think a lot of it like everything in life and especially in this business is relationship-based.

It was funny, when I graduated college there was this idea of like you move to Los Angeles and you went to film school for screenwriting and you’ll get a reader job like that. It’ll be no problem. You’ll be able to support yourself. Those days are long past. So most folks I know are either reading for multiple companies or reading is just one of the many things they do.

But I think a lot of that is based on your relationships with assistants, with executives, finding folks that like even if your taste is not the same it’s in the same ballpark so that you know that like even if we disagree about a script we can argue both sides of this to come to some sort of agreement on whether or not we’re going to recommend it.

**John:** When someone is being hired as a reader there’s usually sample coverage that they’re looking at. So, you will have written up coverage on a script, and even if they haven’t read the script that it’s based on you get a sense of like this person can evaluate story. This person can summarize things well enough so I can understand what the plot of a script is.

**Kate:** Yeah.

**John:** One of the biggest challenges I always had as a reader is you read a script and you’re trying to write the summary and how do you even summarize this thing. The story makes no sense. And sometimes, in the course of writing the synopsis, I’m kind of inventing – in the simplification of it I’m trying to create story so there is a narrative thread to go through there.

**Kate:** Ugh, that was always a challenge. I remember one time I got a script where I believe it was four different versions of the protagonist and the way that this was denoted in the script was different levels of gray scale to tell you which version of the protagonist was interacting within which scene. And you’re like I don’t know what the medium gray is after 30 pages. What am I supposed to do to keep up with that? It can be a real challenge sometimes to just even, you know, pick your way through the narrative and like you said try to find some kind of cohesive narrative thread.

**John:** Are most readers still in Los Angeles or with the rise of the Internet are they just spread out throughout the country?

**Kate:** Speaking for the Black List, we have folks who read all over America and some folks throughout other parts of the world. But most folks I know who are reading as any kind of full-time or steady gig are here, because they have other aspirations in the industry and reading is just a part of that.

**John:** And when they say they’re doing it as a full-time gig or a steady gig, is it still a per-script basis where you’re getting paid per unit? You’re getting X dollars for reading a script?

**Kate:** Yeah. I’ve always heard rumors of these fabled studio readers, WGA readers. I have never met one in the flesh. I don’t know if that’s just something that used to exist and no longer exists. But I only ever got paid for script coverage on a by-script basis. I never got any kind of like weekly fee or anything.

**John:** And what are the ranges you’re hearing about in Los Angeles these days?

**Kate:** It really depends. I have gotten paid everything from $10 to $300 to evaluate a single script. So there’s a wide range. I would say most folks’ going rate for kind of a script evaluation is in the $40 to $50 range. I think especially there’s so many folks reading and because the Internet exists and because we’re all on electronic devices anyway all the time it’s a little easier to read a script then like when you were talking about, you know, got to go to the office, got to pick up the paper copies. The fact that you can do it remotely.

So there are definitely some factors I think that have dropped the price a little bit. But I would love to see a world in which reading was like a legitimate full-time gig for many people that had its own union and all that fun stuff.

**John:** Yeah. It’s horrifying that you say it’s $40 to $50 because that’s – I was getting $50 to $65 20 years ago reading at TriStar.

**Kate:** It’s hard out there. When I was reading full-time I was usually reading two or three scripts a day, depending. And then I know some folks who have been doing it for ten years and can do five or six scripts a day. I would occasionally do four scripts a day, but at that point you’re like I have no brain function left at all.

**John:** And reading that many scripts does just burn a hole in your brain. I feel like at a certain point – it was good, like the first 100 or 200 it was very helpful for me as a writer being able to understand what kind of never worked on a page, and also what my personal taste – I never want to write that kind of way because I sort of feel what happens when you try to do that thing. But it ultimately is using some of the same parts of your brain you need as a writer. You’re visualizing all these things. And it can be really sad.

**Kate:** Yeah. But I mean, it’s also super instructive. I highly recommend that most folks, even if you’re not doing it in a professional capacity, even if you can go on a screenwriting forum and pull a bunch of amateur scripts or something just to give yourself the challenge of writing coverage. Because nothing will teach you more about what not to do as a screenwriter then reading a bunch of really bad scripts.

**John:** That’s actually a great idea. I don’t know if we’ll ever do it as a feature, but it would be interesting to take a script and have people just go off and write coverage for it and be able to cover the coverage and sort of see what people are–

**Kate:** Right before I got hired for Black List I was in consideration for another job for a small production company. And it was down to me and one other person to be the kind of assistant executive catch-all role. And they gave us both the same script and they said one of the execs likes this script and one of the execs doesn’t like this script. And we are going to hire based on your coverage.

The script was just this very boring, middle-of-the-road white guy coming of age sexual fantasy. And I told them about it. And I did not get that job. But I was like, “Well, I guess I didn’t want this job anyway because our taste was not going to align.”

**John:** Well let’s transition now to talking about video, because your piece which was great when I read it, as I go back and reread it now it’s like, oh, she actually answers some of the questions that I had sort of in my head about the availability of movies and sort of our misperception of how big some of these video stores really were in the day and where we’re at right now.

And I also want to get into sort of the difference between streaming and online download and stuff like that because they’re similar but they’re not quite the same thing. And even in your piece, I realized today as I was reading through it again, you did have some answers for sort of why some of these movies are missing and there are sort of big structural issues that need to be tackled to get into it.

**Kate:** Yeah. I mean, there’s a lot of issues that keep movies off streaming, off home video. A couple of the big ones, the one that’s most compelling to me is music rights. I’m also a huge music person, so the idea that films can’t be put on home video with their original music intact is just absolutely sacrilegious to me. But at the same time, you know, that’s one of the few ways you can still make money off music anymore is by licensing it to a film. So, like my friend Marc Heuck who is quoted in the piece talks about, it’s much cheaper for most studios to just do nothing with these titles rather than relicense the music and put it out in some kind of official home video release or get it back on streaming.

And that’s a huge bummer. There are so many movies for which the soundtrack is an essential part of them and the idea that that’s what’s keeping them out of the public sphere is a huge bummer.

I would say for a lot of the ‘90s indies it’s really interesting. A lot of those production companies have since folded and like even the parent companies have folded. So then it becomes a chain of title situation of like do the rights revert back to the producer, the director. Who ended up with the rights to these films? And most of the time you can’t see your way through the darkness and so it’s very difficult to get those films on streaming. But, you know, these movies are 25 years old and all of a sudden unavailable and you’re like, guys, this is going to be like a second silent era kind of erasure if we’re not careful.

**John:** So, before we get into fixing the problem, let’s talk about the scope of the problem. I think most people’s perception is that when Netflix by Mail existed that kind of solved the problem. It seemed like it solved the problem because any movie you could possibly imagine, oh well, it was available on Netflix by Mail before it was even “By Mail” back then. That sense where they would send you a little disc in a red envelope and it would come and show up.

Obviously it was a solution only for movies that existed on home video. It was only for movies in North America. Obviously we’re in a global world, but right now we’re just focusing on what happens in the US and Canada. But for a while it seemed really good and it was very hard to think of a movie that you’d want to see that wasn’t available sort of through Netflix.

As Netflix moves to streaming, I think most of us, myself included, just sort of assumed that well obviously they’re not going to be able to have all the same kind of content there, but it’s just bits. So it sits on a server someplace and if one person a month wants to watch that movie, great, it’s going to be available for them to watch. That’s not at all what happened.

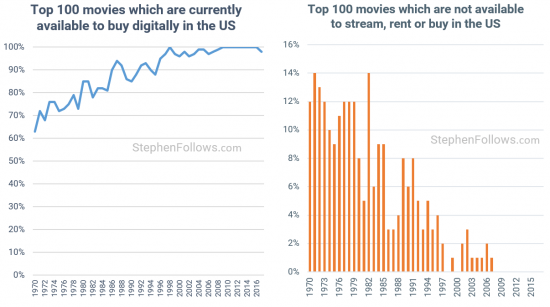

So, in your piece you talk about Netflix at the time of your writing has about 3,686 films available for streaming at any point. But even like a Blockbuster back in the day could have 10,000.

**Kate:** That was a really mind-blowing stat to me. I would have never guessed that my local Blockbuster was stocking 10,000 movies and then putting that next to the Netflix number you’re like, “Wait a minute, so we just get like drama, children’s, and comedy.” And so much of the Netflix content is original and from the last ten years. I mean, that’s a whole different conversation, too, the idea of classic films that are kept off of streaming. I mean, Netflix only has 100 movies on the service from 1900 to 1990, which is absolutely insane.

**John:** And so we can’t rely on Netflix to be the solution to all the problems and obviously Amazon Video has their own streaming services, but Amazon and iTunes/Apple they also offer the ability to rent or to purchase these movies. And I guess I assumed that that was going to be the other solution, because it feels like once a movie is available for purchase or for rental through those sites it can sort of just be permanently there. And at least in your article I can’t find a listing of sort of how many movies are available for rental or purchase on iTunes or through Amazon.

**Kate:** iTunes I have not also been able to figure out. Amazon you can look at through Just Watch, which is the website I used for much of the piece. And that will list everything that’s available for rental. But you know the way I think about that is particularly like I’m thinking about this a lot in terms of the young film fan, kids, teenagers who are just getting into movies. You know, if you’re 14 are you going to watch the free movie on Netflix or are you going to go to your parents and be like “Can I have the credit card, can I do the $3 movie purchase?” No, you’re going to pick the free stuff or you’re not going to watch anything or you’re going to watch YouTube clips. And, you know, I will gladly pay $2 or $3 to rent something on Amazon or iTunes or whatever, but you know, that’s still not fixing the problem that’s still gatekeeping in a way.

My friend, Kate Barr, at Scarecrow in Seattle said the most interesting thing about Amazon and Netflix in particular and she was talking about this idea that for her it’s a First Amendment issue that, you know, when home video began it was suddenly freedom of choice for people in a way that they had never had before. You could pick exactly what you wanted to watch when you wanted to watch it. And in a weird way we’ve come full circle to like limiting our choices again. Like we went from having so many choices to not as many choices, even though it seems like streaming is more accessible.

**John:** Yeah. So I’ll push back a little bit on some of that stuff. I mean, First Amendment, it’s not government control, but it is that access, that sense of I need to be able to access culture and I am being denied the ability to see that thing of culture because of weird corporate restrictions. I think what is so great about the piece you did on Scarecrow Video, so we’re going to link to your main article, but you have done great follow-ups at other video stores and talking to the folks who run these video stores, many of which have become non-profits because they’re really about access to these movies rather than trying to earn a buck.

I would say that we can have this sort of golden age idea of like, “Oh, I could get to all those movies because I could go to Scarecrow Video or I could go to these places and all those movies were there,” but that relied on your ability to actually get to those places.

**Kate:** Sure.

**John:** And so for kids who grew up in rural Iowa there was no video store, so they were completely dependent on what would show up on TV or what was available at their little small tiny video store. I guess what’s surprising is even those small video stores had more than I think we sort of remember them having.

**Kate:** Yeah. I mean, I would say two things about that. I think something that became really apparent to me in writing this piece was how much I had undervalued and I think how much most of us undervalued the video store as a living library archive, as just kind of a history of record. Because, you know, it doesn’t matter what the quality of a movie is, you know, for new releases most video stores are buying all new releases every week. When you start doing that you start to build up a pretty robust collection of stuff and that also kind of catches movies that might slip through the cracks otherwise. And nobody really thinks about that when they think about video store erasure. Like I think about some of the great video stores have closed and it’s like what happens to all these movies when they do close?

I would also – I have not figured out a way to zero in on this, but you were talking about the idea of what was available to folks on television, like to me that is something that has significantly shrunk, too, the kinds of movies we show on TV. Like when I was a kid I watched a ton of weird stuff on IFC and Sundance and movies like Kissed that have never even been put on DVD. And to me now cable is about 250 movies that we have decided we’re going to show and that’s it. And I don’t know if that’s also a licensing issue and with streaming, but to me that’s a huge pool that shrunk, too, and it’s much harder to stumble upon something on cable.

It’s just like, hey guess what, it’s Ghostbusters or Pulp Fiction again.

**John:** Yep. So you talk about video stores used to be kind of the movie libraries of a community, and so obviously one solution to that is the actual library. Andrew in LA wrote in based on what we talked about last week saying, “A couple years ago I discovered what a great resource the LA Public Library is for movies that were otherwise unavailable online. I was one of the first holdouts with the Netflix DVD subscription so I could have access to older, more obscure stuff, but I found that the library had all that was on Netflix and more. The Flamingo Kid is no exception. Just a suggestion for next time you run into that issue.”

**Kate:** Yeah. When I was a kid we rented from the library I would say maybe about a third as much as we rented from Blockbuster. All I had as a kid was Blockbuster, so that’s where we went. But, yeah, the library is an incredible resource. Also I know there are certain library subscriptions where like they will put the catalog online so with your library card you can then stream titles which is really cool.

But, yeah, these kind of creative solutions to working around the streaming bubble. I think people don’t realize there are still – at least when I wrote the piece – there are still at least 90,000 DVDS that one can rent from Netflix online, which is pretty nuts. Part of me has wondered if I should go back to disc Netflix, which is like a very weird thing to do in the Year of our Lord 2018. And, you know, those DVD subscriptions are still playing quite a bit of Netflix’s overall budget for the year. So, people are still doing it. People still want access to more films than what is at the streaming service at any given time.

**John:** As a WGA board member I also have to bring up the issue that while the ability to get to those discs is fantastic for people who want to watch those movies, those discs that are sitting at the LA Public Library that were sitting at Blockbuster, they earn nothing for the writer. So figuring out how to make this available for streaming, for rental, for purchase online is actually very meaningful to any writer, director, actor who is relying on residuals from these movies, because if you were to go stream Charlie’s Angels I get paid for that. If you go find a DVD, you get it from Redbox or you get it from the library, I don’t get paid for that. So it’s worth solving on many fronts and not just sort of like getting access to those physical things again.

**Kate:** Yeah. I mean, that’s something definitely to think about. This is something like I was talking a little bit about the ‘90s titles. For all of those creative teams, and like that’s so unfair to them that just because the company who put it out folded that they now have no ownership over this title anymore. And those rights should, you know, of course there are legal – all that kind of stuff you have to go through and hoops, but the chain of title on that stuff should revert back to the creators at some point if there is kind of no powers that be left.

**John:** Yeah. So, let’s talk about the legal teams involved here, because as you look at classic film preservation, so there’s the kinds of movies that are in the danger of being lost to history because the only print was in a vault someplace and it’s falling apart, and so we have these really smart chemists and colorists who go through and they save these movies and then we do a giant projection, 70mm, and everyone cheers because this movie has been saved.

For every one of those movies there’s thousands that are not being saved because they only exist on VHS or they sort of never really came out on video. And those are the movies that we need to be able to salvage. And it’s not that there’s no copy of them available, there’s just no legal copy of them available. There’s no way to actually get to it. And I kind of feel like we need that band of lawyers and sort of paralegals and other folks who can just figure out the copyright on the stuff and get those things out there the same way we have the chemists and the colorists saving those big prints, just so that we don’t lose this kind of culture.

You talk about sort of a silent moment, especially movies in the ‘70s, ‘80s, early ‘90s that are in real danger of just being lost because they are unavailable. There’s no place to find them.

**Kate:** Yeah. And I mean to say nothing of all of the kind of home video ephemera that arose as a part of that whole movement, you know, where you’d get trailer compilations or a behind-the-scenes documentary, or cartoon compilations. All of that kind of stuff has also vanished. And, you know, most streaming services aren’t offering those kind of special features, bonus features, and that’s as much of a content apocalypse as the movies themselves, like just getting rid of all of the kind of additional materials that were attached to that.

**John:** So, overall goals. We talk about film preservation and film history, sort of the chemists who are making those prints actually work. We talk about the archivists and sort of the film buff, but also the film student. And so those folks are going to be able to find that collection of animated shorts. If someone is willing to put in five hours to sort of discover this place and to drive to that place and find that one copy of something, she’s going to be able to find it somewhere. At least for now she’s going to be able to find it somewhere. But I think your point about the kid who is used to just being able to get everything online immediately is not going to seek that stuff out and there’s a whole bunch of culture that’s going to be lost because that kid is not going to have any way to sort of find it.

**Kate:** Yeah. And I mean I have this argument with folks all the time of like, you know, “Well kids are curious. They’ll figure it out on their own.” I’m like, no, not if they don’t have the tools. Not if they’ve never been to a video store before and not if they’ve never used a library archive system to like truly dig for something. Most of us have lizard brain. Like we just want instant gratification, whatever is easiest. And, you know, as these things become more and more challenging to find and there are other distractions it becomes easier to just be like, “I’ll get to that later.”

**John:** Mm-hmm. So things are holding these movies off, and Marc Edward Heuck had a really good point that you mentioned in your blog post about music rights. And so this really makes sense, because as a person who has made movies when you are putting a song in a movie, you’re putting a piece of existing music in a movie, you are buying sync rights and mechanical rights which are the ability to include that song on a soundtrack of your film.

And along with that you might say like this is for theatrical distribution, so this if for a certain number of years of home video. And you may no longer have the ability to have that song in your movie, which is really a challenge when it comes time to actually try to release that movie again on home video. If you don’t control the rights of the thing that’s in there, either you can’t do it yourself, or you can’t sell it to somebody who would put it out on home video because they worry about getting sued.

**Kate:** Yeah.

**John:** Have you talked to anybody who has been through this situation or do you have any sense of how you sort this out?

**Kate:** That’s a great question. I know that there have been some films released with alternate soundtracks in the last couple of years, or put on streaming with alternate soundtracks. And, you know, is that better than not being able to see the film at all? Yes. Is it a bummer that you can’t see the movie as it was originally made? Absolutely. I would love to get more of a pulse on the whole music rights situation because so many of my favorite films, like Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains, it’s like you strip the music from that there is no movie. And like that’s a DVD that’s out of print. It was in print for a couple of years and now is like $50 on the used market.

Yeah, but I am not entirely sure what can be done to kind of rectify that because that’s also a problem with the record industry and the way online availability of music kind of tanked the entire record industry. And you’re like, “Oh, but we can get some pennies out of relicensing this for movies or television.” So I understand where the record companies are coming from. But also it feels like there needs to be a more reasonable solution for both parties.

**John:** Well also it feels like it’s very much targeting the movies that set us off, which is the early ‘80s movies which would have had pop songs of the time and things could just be complicated. Those were also companies that were bought and sold multiple times. The Flamingo Kid was MGM, but like who knows – MGM has been so many different things over the years. That entire catalog has come and gone a zillion times.

**Kate:** Yeah. It’s wild when you think about all the tiny production shingles that have since folded and then, you know, just what happens to these movies when that company no longer exists. Yeah, like Little Darlings is another big one for me that’s really hard to find and that’s got a bunch of very expensive music cues. There’s a John Lennon song in it. And that has been broadcast once on TCM like several years ago and that’s the only way you can see that movie if you can’t find a VHS tape, which is a huge bummer.

**John:** Marc’s piece also talks about The Heartbreak Kid, Stepford Wives, and Sleuth, which basically were made by a secondary studio. They were made by a smaller company, and so a bigger company buys them out and really has no interest in putting those movies out because it doesn’t feel like it’s going to be profitable for them to put them out. They want those titles because they can be remade. And so they want them for the remake rights, not for the actual underlying thing itself.

And I don’t know how you pressure them to actually do anything. And I do wonder if there is some legislation, some sort of bigger movement to get these titles sort of set free. The challenge is who pushes that? The copyright holders have a vested interest in not changing anything. And so it’s going to have to be filmmakers who sort of insist that their early works be released into the public sphere. It’s the kind of thing where in France it would be actually easier for those filmmakers to probably get stuff to happen than it is here.

**Kate:** Yeah. Something really interesting that happened, so Dilcia Barrera, a programmer at LACMA, reached out to me after the piece and was like would you like to show Fresh Horses at LACMA? And I was like absolutely. So, Sony did not have a functional print of Fresh Horses, so they struck a brand new beautiful 35mm print for the screening. And now there’s a chance that it might be put out on Blu-Ray because this new print was struck. So I think that’s an interesting piece to consider, you know, if you demand these movies theatrically and that kind of forces the hand of companies to make new prints. Even if it’s a digital version, whatever.

**John:** Great.

**Kate:** Just a new version of the film that could then be put on streaming or released on home video, that’s awesome.

**John:** Well, Kate, what you’re saying, which is very encouraging to me, is that it’s not that the negative had been lost to all time. So they had a negative. So if you have a negative you can make a beautiful digital version of it and that digital version can go out.

So do you know anything about what was the hold up with Fresh Horses? Was it a music issue? Why had it gone off–?

**Kate:** Fresh Horses was released by Hemdale which I’m fairly sure does not exist and has not existed for many years, but I mean, Hemdale also put out Blade Runner. What was I just watching this weekend that was a Hemdale movie? Oh, Miracle Mile from the ‘80s.

I would just assume that they folded and whoever the kind of rights defaulted to are like “We don’t need to do anything with movies like Fresh Horses or Miracle Mile.” I know Miracle Mile got a Blu-Ray a couple of years ago and obviously like Blade Runner has many home video editions, but you know, that’s a beloved and classic film, so it’s a little easier to figure out the rights situation for that than something like a Fresh Horses, which is not as beloved.

**John:** This idea of being able to watch Fresh Horses, it seems odd to do a screening of Fresh Horses because it wasn’t like a masterpiece that everyone was clamoring for, but it is very true that most people who are going to see this movie are going to see this movie on video. And that’s true even for the movies that are coming out next week at the cinema, most people are ultimately going to see that movie on home video and how do you make sure that that home video is going to still be around 20 years, 30 years, 40 years down the road?

**Kate:** I am really disturbed by the fact that Amazon and Netflix seem to not care about putting any of their original movies or TV series on disc. Like I know Stranger Things got a disc release, but like people really had to pressure Amazon to get Blu-Rays of Wonderstruck. And to me that suggests a scary overall trend for those companies that they’re treating these products as disposable. It’s like we’re not even going to put it on any kind of permanent format. It’s either on the streaming service or it’s not on the streaming service. And that’s a bummer for folks who still like home media, who want to guarantee that they will have these movies or TV shows in perpetuity.

Yeah, and I think there is a market for home video, especially as home theaters become more and more in depth and people get more into the idea of movie screenings in your own home. I just wish more folks would realize that.

**John:** I just saw the trailer for Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, which is a Netflix film, black and white, gorgeous-looking, at least from the trailer. I mean, of course it’s going to be gorgeous. He’s an incredibly talented filmmaker. But it will be fascinating to see is there going to be a Blu-Ray for Roma? Because it’s going to come out theatrically and on Netflix. And for Alfonso Cuarón as a filmmaker, fantastic he got to make exactly the movie he wanted to make. He probably got the budget he wanted. It’s great for cinema that Netflix stepped up and sort of helped him make this movie. But I do wonder whether it’s great for cinema ten years from now, 20 years from now that this was made for a digital platform that has no vested interest in the long term existence of a physical version of this thing?

**Kate:** Yeah. I mean, that’s a really good example. I feel like also Scorsese’s The Irishman is going to be a real make it or break it moment for Netflix. You know, the idea – if we’re not giving home video releases, if these are films aren’t getting nominated for Oscars, if they’re not picking up theatrically. You know, the Irishman especially is about as prestige of a prestige project as you could get, and popular as a prestige project could get. And if that doesn’t get the kind of reception that a normal theatrical release might then I think that kind of indicates where the vibe is on Netflix in terms of how they’re going to release prestige movies going forward.

**John:** Yeah. It’s easy to look at Netflix now, which is so successful and everybody has it and it’s thriving, but there’s lot of companies that just go away. And if Netflix just goes away, what happens to all those things that were made for Netflix? And it’s not entirely clear. And folks who I know who have made deals with Netflix, no one I’ve talked to has anything in their deals that says like if the company doesn’t exist ten years from now I get the rights back to something.

**Kate:** Yeah. That’s got to be really sobering as a creator. I mean, I figured this out when I was writing the piece. Only ten years ago Netflix had their first production arm which was called Red Letter Media, which has since folded. So I think it’s really hard for anybody to try to predict where Netflix or any of the streaming services are going to be ten years from now. So much has changed.

**John:** Speaking of so much has changed, so this is a thing that’s been recurring on the podcast and we could probably do a segment on it every week, but this past week it looks like MoviePass has gone under. If it hasn’t officially gone under, it’s about as close as you get to going under. The stock did a reverse split which I didn’t even know was a thing. It’s worth very little. And people who try to leave the service are being prohibited from leaving the service. What’s been your relationship with MoviePass?

**Kate:** So I got MoviePass at the end of last year. I did the annual $90 one. I’ve gone to about 12 movies, so I’m like it paid for itself. Great. I have a lot of friends in the LA rep scene in particular who have really been using it to go to way more rep screenings than they would normally ever go to. And to me that’s a bummer with like the loss of MoviePass is the ability to see more movies than you would on a normal budget.

But, yeah, you know, I do think MoviePass is ultimately going to be a good thing to show that there is an appetite for these kind of pass programs. I would love it for instance if all the LA repertory theaters would ban together and be like, OK, you pay $25 a month and then you get X number of tickets to the Egyptian, the New Beverly, etc.

But I mean the MoviePass flameout has been kind of spectacular to watch on film Twitter, because, you know, it’s a totally unsustainable model. We all knew–

**John:** Yeah. We knew it was. This is all going to end in tears. It was like taking Omarosa into the White House. Like it wasn’t going to last. You knew it was doomed.

I think on the whole MoviePass you have to see the pros of it, in that for about a year a bunch of VC money gave people free movie tickets.

**Kate:** Yeah.

**John:** And so it helped the movie industry and it allowed people to see more movies. I think it definitely got more people to see the indie films because it’s like, “Well, I got to use this thing. I’ve seen everything else. I’m going to go see this movie.” And I think that does help those things.

You’re the first person I’ve heard talk about this idea of an indie pass that sort of goes to all those smaller chains. That would be fantastic.

**Kate:** I would be amazing.

**John:** If it helps keep those art houses in business the same way that we need to keep video stores in business that would be fantastic. Bigger chains, AMCs, have rolled out their own plans which seem great. And I guess I’m all for studios figuring out deals with those exhibitors just to sort of get butts in seats and keep butts in seats. Because what MoviePass did show is that people do want to still go to the movie theaters. There’s this myth that as home screens get better, as TVs get better people are just going to stay home and only watch movies on their TV screens. And it’s like, no, people actually want to go out and be with people and see movies.

And what was partly doing MoviePass in is that young people with friends were like well we all have MoviePass, let’s go out and see like three movies. And they would.

**Kate:** Yeah.

**John:** And if we can encourage that behavior that’s awesome.

**Kate:** Yeah. It’s interesting. I would say I definitely know a lot more young folks that got really into MoviePass, but I’ve also talked to some folks that like their parents – this became a huge thing to get them back to the theater after many years of not going to the theater. You know, the idea of a deal suddenly becomes more exciting.

But, you know, last weekend, I went last Sunday. I went to a matinee of BlacKkKlansman at the ArcLight that was almost sold out. And then that night I went to a screening of Wanda at the Egyptian that was sold out. It was in the small theater, the Spielberg. But, you know, obviously we’re in the movie capital of the world so that’s necessarily the best comp for most of the country.

But I do think that, you know, when you make these options easier for people to get on board with, how about that, they go back to the theater. It’s not rocket science. And I would hope folks realize the void that MoviePass will leave and we get an indie pass, or more subscription programs from major chains. Because I do think that people like being among other people. Like I really enjoy, this is a similar thing with video stores, even if you don’t talk to anybody else, you don’t like meet up with friends, just being among other people, not in front of your black computer screen, in very nice.

**John:** And your pieces on the different video stores you visited, I think that sense of community was really crucial and something I’d kind of forgotten. Is that while my local Blockbuster was just like whatever, who cares about that, when you go to a place that’s genuinely a video store with people who like love movies, not just the employees, but the people who are wandering through the aisles looking for stuff, they can give you recommendations. You can see the taxonomy is very much set up based on a hive brain of like these kinds of movies belong together even if it’s not sort of genre wise which you’d expect.

You have some maps of some of your interior layouts of these video stores that really show how they’re thinking about movies and how stuff fits together. Bookstores, which are thriving these days, smaller bookstores are thriving these days, I think it’s the same sense. That people want to go to a place where people kind of care about the things that are on the shelves.

**Kate:** Yeah. It was really interesting. Last Saturday I went up to Odyssey Video in North Hollywood which is closing unfortunately. It was an extremely cool video store. They had a lot of rare VHS still, particularly on the children’s side of things. But that was really interesting because it’s an everything must go kind of sale. So they’re selling off their entire stock. But it was a Saturday afternoon at four o’clock and there are 25 people in this video store right now. And we were all extremely amused. There was this extremely precocious kid who was just like running around being like “Do you have Poltergeist? Do you have Pretty in Pink? Why can’t I go in the back?”

And, you know, it was really invigorating to see like an 11-year-old kid just like so excited about movies, about picking up the physical movie, like crossing movies off the list. And like, I don’t know, streaming is just never going to generate that kind of enthusiasm. Like I don’t care what anybody says. That kind of tactile human community experience. We’re just never going to get that via a streaming platform.

**John:** You’ve convinced me. So I would say, and as recently as three weeks ago I was having a little Twitter disagreement with Robin Sloan, an author, and he had basically the thesis of video stores, things were better in the video store era. And I said, yes, if you compare to streaming. But if you add in iTunes, there’s actually more availability. We don’t have the real numbers to see sort of how many things are on iTunes, but I’ve been convinced over the past few weeks that something really has been lost as we’ve transitioned so thoroughly away from physical media that some stuff is just very hard to find.

And when I actually finally had to go out and get a physical copy of The Flamingo Kid, I realized like I have no player that can actually play this thing, which is a very strange place to get to in your life. Where I have all these drawers full of DVDs that I haven’t watched in a long time because instead I just watch Netflix or I watch iTunes. And I’ve actually found myself being guilty of like I think I have a DVD of that, but it’s actually just $2.99 for me to get it on iTunes, and so I just look for it on iTunes. And in some cases the iTunes quality is better. So it’s not a crisis to do that. But I’m not going back to those DVDs very often. And the existence of physical media is sort of a bulwark. It’s a protection against things being lost.

**Kate:** Yeah. My friend Matt Shiverdecker is very in the loop in terms of home video licensing and who owns what and that kind of thing and he has one of the most impressive home collections I’ve ever seen. And he has just kind of a running list of, you know, here are things that never got put on DVD that I love. Here are things that never got put on any kind of HD transfer that I love.

I mean, it’s shocking some of the things that aren’t available. A couple of months ago I was looking for Cronenberg’s Crash and I ended up watching it on YouTube with Spanish subtitles because that was the only version of the movie I could find. And I was like this was an important movie in the ‘90s. The fact that this was only on an out-of-print DVD right now is crazy. Cronenberg is a major filmmaker.

**John:** Yeah. Well, we need to talk before we wrap this up, we had to talk about piracy, because in some ways piracy is both the answer to and the cause of a lot of these problems. Is that without piracy some of these things would be impossible to find. If you hadn’t found that bootleg Spanish thing on YouTube you would not have been able to watch that. So, good that it exists there, sort of, with an asterisk. But piracy is also part of the reason why these companies feel like it’s not in their interest to try to make a legal version of it available because they’re like I could spend all this time figuring out the rights on this thing, getting it on iTunes, getting it on a streaming service, and I’m not going to sell anything because someone is going to just get the pirated version. That’s what happened to the music industry. That’s what’s going to happen to me. So–

**Kate:** It’s a tough conundrum. I don’t know what the good answer is to that because, you know, I would say I did a lot more torrenting and illegally watching of movies like ten years ago. And I would say it was much easier to do then than it is now.

But there are many things you’re like, you know, I have tried the legal methods. I have done my diligence. If I can’t find it, I’m going to watch the illegal version. Like, I’m sorry, and thank god that there are still people who put movies like Crash and Times Square up on YouTube to find, because otherwise then we can’t access the movie. And that’s really terrible.

**John:** Consolidation in the industry has left us with so few companies controlling so much. And some of your folks have acknowledged as you’ve talked to them about their video stores is that in a weird way we ceded control to giant corporations who are ultimately gatekeepers of like whether a thing can be seen or not. So, between Apple and Netflix and HBO, sort of those, and art studios which are so small, in some ways the zillion companies that made all these movies it was better because there were multiple people producing films. They were going out to many, many venues. There were video stores all across the country. And as the funnel gets narrower and narrower, I don’t know if this actually happening, but if someone at Apple really despises a certain movie they could just make the movie not available. And there’s really sort of nothing we as a culture or as that filmmaker could step up and get in the way of that.

**Kate:** Yeah. I mean, you know, losing that kind of personal choice that video stores provided where you were not at the mercy of corporations. Where you could rent a Hitchcock classic and like a garbage horror movie and like a kid’s program all in the same day. When that control is given to major corporations who have bottom lines and financial interests to hit, you know, they’re not going to put stuff on the service that nobody is watching. They’re not going to put stuff on the service that nobody is taking note of. But that doesn’t mean that those films still aren’t valid and deserve to be seen by the people who want to see them.

**John:** Cool. As we wrap this up, do you have any recommendation for a film that people should check out and where they should find it if it’s hard to find?

**Kate:** Ooh, interesting. I feel like I could go all day on this kind of subject. Let’s see. I was just talking about I found Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains on DVD, which was great. I’d been looking for that one for quite a while. So, something I would recommend, if you guys don’t have FilmStruck, you’ve got to get FilmStruck. They are really picking up a lot of the slack in terms of classic movies. And not just, you know, when we think of classic movies we think of like ‘50s epics, but you know like Bill & Ted is currently on FilmStruck. So, it’s a tide that raises all boats.

But my favorite thing on FilmStruck is Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky, which is completely unavailable elsewhere. It’s this incredible gangster movie with John Cassavetes and Peter Falk. It’s most famous because Elaine May fought like hell with Paramount about the final cut. At one point she stole the print from them and was like hiding it in her garage because she didn’t want them to keep tinkering with it. This movie is very hard to find and it is now on FilmStruck, so you’ve got to check it out.

**John:** Fantastic. FilmStruck I’ve not used yet but I definitely will. Rian Johnson loves it and tweets about it a lot. So that will be fantastic.

All right, it comes time for our One Cool Things. So this is where we recommend things that are out there in culture that people should go out and see or read. In my case it is a book. It is My Life as a Goddess by Guy Branum. It is fantastic. So you will probably recognize Guy because he’s often a guest on talk show kind of things. He’s a comedian. He’s been on Midnight, Larry Wilmore’s show, Chelsea Lately. But this book he’s written is fantastic.

So, it details sort of his growing up in rural Northern California, sort of the agriculture community. It’s just great, great writing and he’s really, really funny. So, Mindy Kaling who was our guest two weeks ago, she wrote the forward to the book and she’s exactly correct when she says that it is fantastic and you should check it out. So, Guy Branum’s My Life as a Goddess.

**Kate:** That sounds great. I’ve been hearing a lot of really wonderful things about that book. I’ve got to check it out.

**John:** It reminded me of Lindy West’s book, which I also loved, and sort of because Guy is a big, giant guy. And it reminded me some of what she wrote about in her book. But the specificity of where he grew up and what his life was like was fantastic. And not to spoil too much about it, but My Life as a Goddess refers to this Greek goddess who suffers all these challenges and then at one moment realizes, wait, I’m a goddess, and just transforms everything around her. And that sense of recognizing your own personal self-power is great.

**Kate:** Sounds awesome.

**John:** Cool. Anything more you want to recommend? Because you just made a great recommendation on that film.

**Kate:** Yeah. I’m going to plug a great movie t-shirt website. It’s called Tees-En-Scène. It is Colin Stacy who is a wonderful dude in Texas who has taken up the mantle of making these incredible t-shirts that highlight female writer-directors mostly. There are two out right now. There is the Elaine May t-shirt who we were just talking about. And then he just put out a t-shirt for Barbara Loden who made Wanda. He’s got an Amy Heckerling t-shirt in the pipeline. But they’re really cool because he pulls the frame of Written and Directed by from the movie itself on the t-shirt so it’s not just like boring text.

**John:** Oh neat.

**Kate:** He’s got Kathleen Collins coming up. And also some of the proceeds are funneled back to women of color filmmakers. So you get to get a dope t-shirt and you get to support a great cause. Check it out, Tees-En-Scene, or if you want to google Elaine May t-shirt, Barbara Loden t-shirt you can find it.

**John:** Very, very cool. All right. That is our show for this week. As always it is produced by Megan McDonnell. It is edited by Matthew Chilelli. Our outro this week is by Luke Davis. If you have an outro you can send us a link to ask@johnaugust.com. That’s also the place where you can send longer questions. But short questions are great on Twitter. I’m @johnaugust. Craig is @clmazin. Kate, are you on Twitter?

**Kate:** I am. I’m @thathagengrrl like Riot Grrl.

**John:** Fantastic. You can find us on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. But I will note that podcast feeds are actually directory based, and so Apple does not control your ability to get to our podcast. So, you really could find us any way. You could just type it into your little browser of choice and it would still be there. So for all the talk about like, oh, censorship control, podcasts are still an RSS-based medium. They’re still available out there in the world. They’re more free like the web than people think they are. Apple doesn’t actually host us. We’re just sort of out there.

But you can find us anywhere, just search for Scriptnotes. If you find us on a service, leave a comment because that helps people find the show.

Show notes for this episode and all episodes are at johnaugust.com. We’ll have links to Kate’s pieces that she’s written for the Black List. You’ll also find transcripts for our show at johnaugust.com. They go up about four days after the episode airs.

All the back episodes are at Scriptnotes.net. We also sell seasons of 50 episodes at store.johnaugust.com.

Kate Hagen, thank you so much for coming on to talk to us about reading and video and some great recommendations.

**Kate:** Thanks so much, John. And just one final thing. If you’ve got a video store in your neighborhood and you haven’t been there yet, what are you doing? Go to the video store.

**John:** Go to your video store. Thanks Kate.

Links:

* Thanks for joining us, [Kate Hagen](https://blog.blcklst.com/@thathagengrrl)!

* [In Search of the Last Great Video Store](https://blog.blcklst.com/in-search-of-the-last-great-video-store-efcc393f2982) by Kate Hagen

* [The Black List](https://blcklst.com/register/highlights.html#industry)

* [Netflix’s DVD service](https://dvd.netflix.com/MemberHome)

* [Fresh Horses](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SF2wY3uJdng) was one of those missing movies.

* [The Fall of MoviePass](https://variety.com/2018/film/news/moviepass-ending-subscription-service-1202891561/) and its [reverse stock split](https://deadline.com/2018/07/moviepass-parents-stock-plummets-44-after-reverse-split-takes-effect-1202433444/)

* Kate recommends [Ladies & Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06kCwPpyjCk), [Mikey and Nicky](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_qMg8ZG0ic) and [FilmStruck](https://www.filmstruck.com/us/?utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=MIDF&utm_term=filmstruck&utm_content=A200_A203_A015526&c=A200_A203_A015526&pid=adwords&cid=ppc_adwords_A200_A203_A015526&creator=Fetch&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIv_z-toj93AIVl6DsCh1Y0QjEEAAYASAAEgLAkfD_BwE) to watch classic movies.

* [My Life as a Goddess](https://www.amazon.com/dp/B075RNFTTW/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1) by Guy Branum

* [Tees-En-Scène](http://www.teesenscene.com) sells shirts that highlight and support female writer/directors.

* [The USB drives!](https://store.johnaugust.com/collections/frontpage/products/scriptnotes-300-episode-usb-flash-drive)

* [John August](https://twitter.com/johnaugust) on Twitter

* [Craig Mazin](https://twitter.com/clmazin) on Twitter

* [Kate Hagen](https://twitter.com/thathagengrrl) on Twitter

* [John on Instagram](https://www.instagram.com/johnaugust/?hl=en)

* [Find past episodes](http://scriptnotes.net/)

* [Scriptnotes Digital Seasons](https://store.johnaugust.com/) are also now available!

* [Outro](http://johnaugust.com/2013/scriptnotes-the-outros) by Luke Davis ([send us yours!](http://johnaugust.com/2014/outros-needed))

Email us at ask@johnaugust.com

You can download the episode [here](http://traffic.libsyn.com/scriptnotes/scriptnotes_ep_364.mp3).