I’ve added two .pdfs to the [Library](/library). (Which is the rechristened “Downloads” section. Thanks to whichever reader suggested renaming it.)

* The visual FX breakdown for two of the sequences — the end of Part One, and the end of Part Three. Both are spoilers, so skip them if you haven’t seen the movie yet.

* The shooting schedule. This is pretty close to how we ended up doing it.

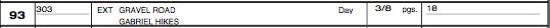

Shooting schedules are hard to read if you’ve never looked at one, so let me talk you through it.

Starting at the left is the strip number. Because some scenes may have more than one part — for instance, a visual effect in addition the main action — you sometimes (rarely) need to refer to the strip rather than the scene number.

Next is the scene number. For The Nines, we numbered all of the Part One scenes in the 100s, Part Two in the 200s, and Part Three in the 300s. Most movies would just go sequentially from 1. [Read here](http://johnaugust.com/archives/2007/renumbering) for more info on scene numbers with letters.

The third column is a short description of the scene, along with INT or EXT, DAY or NIGHT. Note that the line producer or AD writes this description, so it’s not always what the writer would pick.

Fourth column is the length of the scene, measured in eighths of page.

The final column shows which characters are in the scene, by number. Generally, your most important characters are given the lowest numbers, with preference for the bigger stars. In the case of The Nines, our numbering system went as follows:

* Gary/Gavin/Gabriel = 1/5/18

* Margaret/Melissa/Mary = 2/7/19

* Sarah/Susan/Sierra = 3/6/20

To see how much work is scheduled on a given day, look down to the divider strips, marked “– END OF DAY…” This tells you how many pages you’re expecting to shoot.

As you’ll see, we shot 4-5 pages a day — fairly ambitious for a feature, though indies tend to shoot more pages per day simply because limited budgets mean short schedules.

You can find both documents [here](/library).