The original post for this episode can be found [here](http://johnaugust.com/2012/one-step-deals-and-how-to-read-a-script).

**John August:** Hello and welcome. My name is John August.

**Craig Mazin:** My name is Craig Mazin.

**John:** And this is Scriptnotes, Episode 66, it’s a podcast about screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters.

So, Craig, are you writing right now or are you just doing work on The Hangover? What are you doing during your days?

**Craig:** Right now I’m just, yeah, right now I’m just on The Hangover. So, I am writing, but it’s sort of revising as we go, you know, so every day we start our day with the guys and we put the scene up on its feet and then we make adjustments and changes as we need.

So, I’m sort of doing on-the-set writing these days. But I don’t expect I’m going to do any writing-writing until the end of the year. How about you?

**John:** I’m good. I’m in the middle of doing my pilot for ABC. And it’s been good. It’s nice to sort of be able to buckle down and really get going on something. One thing I hadn’t anticipated, because it’s been a couple years since I’ve done television, is outlines are a lot more extensive now than they used to be.

So, for a one-hour drama they’re asking for an outline that’s like ten or 12 pages long, and it’s really pretty detailed. Like it’s really scene by scene what’s-going-on-in-each-scene, complete with suggestion of what dialogue is. And it’s kind of a pain in the ass to write those things.

But, I will say when you’re actually writing the script, it’s really, really easy, because so much of that thinking has already happened. So you know kind of what the structure of that scene is before you get to it. And so it’s just a matter of fleshing it out and making it really be a scene rather than be suggestions. So, that’s been kind of cool.

**Craig:** Yeah. I put myself through that torture on movies because I find that the feeling of not knowing where you’re going or not knowing what a scene should be is so distressing to me that I would rather the pain of a very thorough outline. So, when I’m outlining feature scripts usually I’ll get up to 25 pages of outlining, scene by scene. I just need to know it. That’s my thing.

**John:** With TV I had anticipated that there would be so much discussion and feedback on the outline stage, and I get why they do it because it’s a lot easier to talk about things as an outline. It’s a lot faster to read the outline. But ultimately on those phone calls at some point you do end up saying, “Well, this will be really good when it’s actually a scene and we’re not talking about one sentence in this paragraph.”

So, you have to balance that out. But on the whole it’s been kind of fun to try it this way.

The other new thing I’m trying this time is I’m writing the whole thing in Fountain. So rather than using Final Draft I’m using this unannounced Fountain screen editor thing that’s really good. It’s not something that we internally are developing — someone else is developing — that’s really good. And just today I was printing out pages for Stuart and I printed it out of Highland. And so it looked great. I made a PDF and printed it.

And so it’s been fun to try new tools for it and see sort of how that all works.

**Craig:** Yeah, I promised myself that the next draft that I write of something that’s on my own, that’s not collaborating with somebody else, I’m going to use Fade In, because I feel the need to branch out, shake things up a little bit.

**John:** Here’s my worry about Fade In, or some other brand new screenwriting software, is that what’s so good about this new app that I’m using is — it has been really stable so far — but if it were to crash and completely die, the file itself is just plain text. Like any text editor can open it. I can open in Highland or whatever. So, I’m less dependent.

I would worry that Fade In or any of these other applications might be using something with a format where if it just completely goes kerplunk, I can’t get the script out of there anymore.

**Craig:** Well, I feel a little safer in as much as I know the guy who created it, so I feel like I could just call up Kent and say, “You have to save this for me.” But, also I have the option of routinely exporting the file to Final Draft, it does that, or to any kind of — it’s a very importable/exportable system.

**John:** Cool.

**Craig:** I’m not too frightened. I’m a little frightened now.

**John:** I wish you good luck with it. Please report back as you get started on it.

**Craig:** I will.

**John:** Yesterday I was listening to a podcast called Systematic with Brett Terpstra and his guest on it was David Wain, the writer from The State and many movies, who also does Childrens Hospital, which is brilliant, which you should check out.

And so I’d heard this before from Rob Corddry when he was talking about Childrens Hospital is the writer/producers, they live on different coasts and they do all of their writing collaboratively in Google Docs. And so they just have a big Google Doc open and they all are typing out simultaneously. And because Google Docs can’t really handle screenplay formatted stuff it’s just sort of a rough jumble. They sort of want to use Fountain but they can’t quite use Fountain yet.

But, as each of them is typing, each of them types in a different color so they can see who is doing what revisions at a time. It’s clever.

**Craig:** Yeah. I mean, Final Draft and Movie Magic have this fake version of that. One is called CollaboWriter and the other is called, I don’t know, something or another, but they don’t work because basically any normal network setup sort of disallows this kind of back and forth because of firewalls and stuff like that.

Sooner or later someone, I think what will happen is ultimately Final Draft or Movie Magic will offer a cloud-based version of what they do, or you should offer a cloud-based version of what you do. That would then allow full and free collaboration in the screenplay format. That would be awesome.

**John:** Yeah. Brett Terpstra, who runs that podcast but was also a helpful person early on in the development of Fountain, promises that he’s working on something for Google Docs which I think would be fantastic.

**Craig:** Excellent.

**John:** Would be very, very helpful.

**Craig:** Good.

**John:** So, today I thought we would talk about three different things, sort of a hodgepodge. We’d talk about reading scripts, because we’ve talked a lot about writing scripts, but let’s talk about how you read scripts and sort of technology but also best practices for sort of going through and reading scripts.

I thought we’d talk about one-step deals and what a one-step deal means for screenwriters, why studios love them, why screenwriters don’t like them.

And then we would talk about Skyfall and probably get stuck singing the Adele song to each other for a few…

**Craig:** [sings] Skyfall, when it crumbles.

**John:** Such an amazing song. You said it was the third best Bond song.

**Craig:** You’re saying it is the third best?

**John:** I think you said on Twitter that it’s the third best.

**Craig:** I did. I think it is the third best Bond song, yes.

**John:** Okay, well we can discuss and argue that. Let’s get started with reading scripts, because when I first started out in the industry I read a zillion scripts and the first scripts I read were at USC. And USC had a script library. You could go and you could check out two scripts at a time. And scripts at that time were literally physically printed scripts. They were 120 pages. They had card stock covers.

The USC scripts, instead of having brads in them, they had those cool sort of screw together binder things, like there were little posts that went through the thing and held them together really nicely and strong. And it was just such an amazing resource, like, “Wow, we can check out these scripts.” And so I would check out Aliens, and I would check out all of these amazing scripts of movies that I loved. And that was just remarkable.

And now anyone with a computer anywhere in the world has access to many more scripts than they do before. But, people will often tweet me and say, “Oh, what do you use to read scripts?” And I’ll answer, I’ll answer “my iPad” or whatever. But the fact is I don’t read nearly as many scripts now as I used to. And I’m curious whether you still read scripts?

**Craig:** I do. But I, [laughs] — so I read scripts when I’m sent scripts to read. You know, “Would you like to rewrite this?” I’ll read that. Or, “Would you like to work on this?” I’ll read that.

And I will occasionally also read scripts for friends. So, Scott Frank sent me his script for A Walk Among the Tombstones which he is currently prepping to shoot, I think, in the spring.

Then, beyond that, occasionally I’ll read a script from somebody that says, “Hey, can you help me out and tell me what I should do?” But, I don’t read them recreationally because I hate reading screenplays.

**John:** Why is that? Why do you think that is?

**Craig:** Because screenplays aren’t supposed to be read. They’re supposed to be shot. [laughs] So, the problem is, it’s a weird thing: the screenplay is a literary tool to make a non-literary thing. An audio visual work. And so it’s kind of a bummer to read them. And it requires more mental exercise than reading a novel because prose is designed to help paint the picture for you. There is no expectation that there is going to be a movie afterwards. So, it’s more fun to read prose.

Reading scripts is a bit of a slog. And then, of course, the other issue is because so many of the scripts I read I’m reading with a purpose, you know, “What would you do?” “How would you fix this?” that it’s work. And I guess maybe the last thing I would say is because I spend so much time writing them — you know, you spend all day long cooking steak, you don’t want to eat steak for dinner.

**John:** I would agree with you. It’s like I know editors who will spend all day staring at screens cutting a movie and they go home and watch TV. I’m like, “How can you do that? How can you keep staring at screens?”

For me it’s that I can’t turn off that part of my brain that wants to fix what I’m reading. And so if I’m reading a screenplay, unless it’s absolutely perfect, I will be noticing all the things that I would want to change in it. I’ll be making the movie in my head and rewriting the script as I’m reading it which generally isn’t that helpful, or that good.

So, even if I’m reading a script that’s on the Black List that’s really, really good, it’s very hard for me to go into that and not find all the things that I would do differently. It’s just the nature of being in here. The same way I think many professional athletes have a hard time watching sports on TV. You’re used to playing the game, not watching the game.

**Craig:** Yeah.

**John:** So, when you do read scripts though, Craig, how are you reading them? Are you printing them out? Are you reading them on an iPad? How do you read scripts usually?

**Craig:** Lately I’ve been doing a lot of iPad reading. The bummer about reading the scripts on the iPad — and this is going to sound like such a lame-o complaint, you know. Louis C.K. does this great bit about people complaining that they can’t get internet on their plane. He’s like, “You’re in a chair in the sky.” And so, you know, I feel embarrassed about this, but the iPad is a little heavy, frankly, to read a script on. It starts to be annoying for me.

Now, I ordered the iPad Mini and that thing is awesome. So, maybe it will be more comfortable to read scripts there. But I’ve been doing most of the reading on the iPad. I will read a little bit on my laptop. I don’t print scripts out ever anymore.

**John:** Yeah. I do most of reading — script reading — on the iPad now. I got my mom an iPad Mini for Christmas, and so when she was here for Thanksgiving I gave her the iPad Mini. I gave her the whole tour and talked her through everything. And I hid all the apps on the third page that she would never need to touch and I sort of simplified it as much as I could.

I loaded it full of photos of my daughter so she would have a reason to turn it on, even if she never used it again. But while I had the iPad Mini in the house I did pull up some scripts as PDFs and looked at them, and it’s actually a really good size for reading screenplays. It’s sort of everything I hoped that the Kindle would be able to do, in that it’s just a right good size, except it’s fast and you can look at PDFs and everything looks really good.

And it’s the luxury of screenplays that are 12-point Courier that they’re actually big enough that you can read them nicely and naturally in their normal size. So, I think you’ll enjoy the iPad Mini.

But which application are you using to read them in? Are you just opening them up in mail? Are you going to GoodReader? What are you using for that?

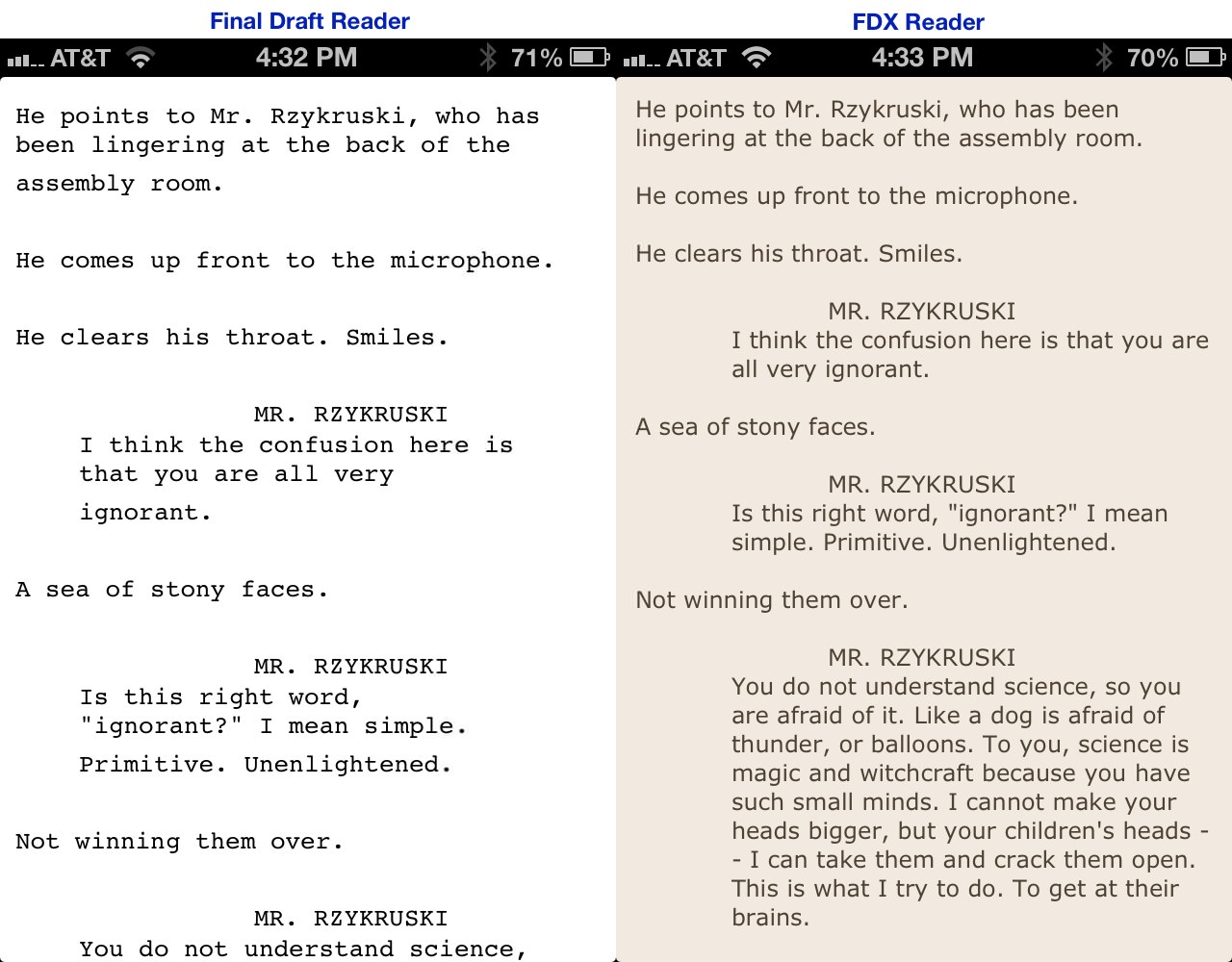

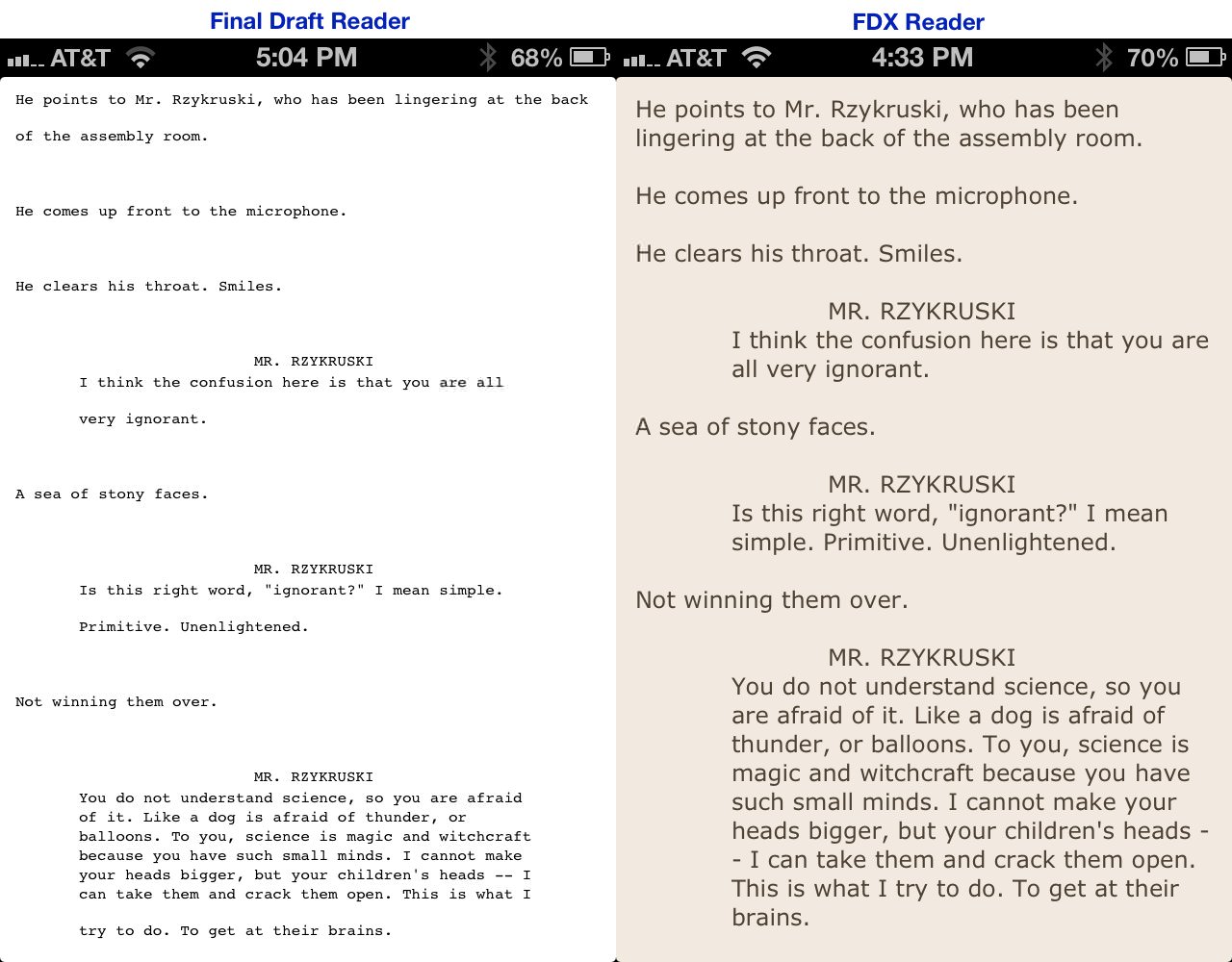

**Craig:** Well, it depends on the format. If I get it in Final Draft then I read it in — I have both your app and the official Final Draft app. I’m not sure which one I’m pointing to right now. If it’s a PDF I usually read it in, usually it’s in GoodReader.

**John:** Yeah, I’ve been sticking with GoodReader. Stu Maschwitz, who also helped develop Fountain, strongly recommends PDF Expert, which I’ve also tried. And it’s been sitting on my iPad for a long time. It just had such a generic icon that I never thought to actually use it. It’s a little bit better for annotations I found.

GoodReader actually works really pretty well, it’s just that it’s really ugly. To me it’s like the Movie Magic screenwriter of PDF readers in that like there are just so many things crammed into every little nook and cranny. It’s like, “Oh, we can add this feature. Let’s put a big button here.” It’s a little bit frustrating to use. So, PDF Expert seems to be a cleaner version of that same kind of thing.

**Craig:** Yeah, I agree. It is ugly. And, in fact, sometimes I’ve sent the script PDFs over to iBooks because that’s actually a nice interface. It’s very clean.

**John:** It is. Yeah. iBooks doesn’t let you annotate the way you might want to annotate, but if you’re just reading a script it’s really good for that.

**Craig:** Yeah, I never annotate.

**John:** Yeah, I don’t really annotate either. I know people who love to do that. I’m just not a big annotator. If I do feel like I need to make changes on a script I do like to print. I like to print my own scripts once before I send something in just so that I can catch the mistakes on paper that I never catch on screen.

I’m a big fan of printing two up on a page. And so you print smaller size, so it’s two — it’s a horizontal page and you’re printing two pages side-by-side. It’s just a way of saving some paper.

**Craig:** Oh, that’s interesting. Oh, by the way, I do the same thing. The only time I print a script out is if it’s my script before I send it in, because you’re right, there’s something about visually looking at each page that you catch errors that you wouldn’t catch on your screen. But when you do the sort of side-by-side version do you also double side print?

**John:** I don’t. I don’t believe in double side print. If I get a script sent from the agency and it’s already bound that way I’m fine with it, but otherwise I won’t double side print. I’ve just never found that useful or helpful.

**Craig:** Yeah. I don’t do it when I’m printing for editing and corrections, but I don’t mind reading a double… — When I first saw them I was like, “Oh god,” mostly because I just get annoyed by these pointless —

Here comes the umbrage. Umbrage Alert! We should have like a signal, a siren, like drive-time DJs for umbrage.

— I get so frustrated by pointless gestures towards greenness. You know, like, “Oh, we send everything out on double-sided paper now.” Well, you know, paper isn’t really a problem anyway and you sent a guy here in a car. You had a guy drive in his un-smog-checked ’98 Tercel to drop your double-sided script off at my house. Just email it.

It just makes me… — The sanctimony of pointless gestures makes me nuts.

**John:** I agree with you

**Craig:** Yeah.

**John:** Yeah. I think the better reason for doing the two-sided is that if you’re carrying a bunch of scripts with you they’re a lot thinner, and so it saves space when you’re shoving ten scripts in your bag. And that is a big advantage to double-sided for me.

**Craig:** True.

**John:** Now, the actual process of reading a script, because most of the scripts I end up reading tend to be for I’m going to be sitting down with this person and I need to be able to tell them what I thought. And so for instance at the Sundance Labs I’m sitting down with these filmmakers, and so I’ve read their scripts and I need to be able to talk with them about sort of the movie they’re trying to make.

And usually in that situation I’m meeting with five filmmakers over the course of a couple different days. And I’ll have read all the scripts like maybe a week ahead of time. And so I find like, well, I need to be able to remember what it is. And so as I first start reading the script, as characters are introduced I will flip back to the title page and I’ll write the character’s names down. And I’ll write the relationships to who they are just so that when I go back to the script I can actually remember “this is who is in the script.” And as I pick up the script again I can feel, “Okay, I can talk myself through this.”

If I have major notes that are about the script overall I tend to write those on the title page. If I have notes of things that come up along the way I fold down the pages and sort of scribble them on the page so I can talk to them about specific things that are happening in scenes.

So, that’s just some guidelines for reading scripts for your friends and reading scripts for people you’re going to need to give notes to.

**Craig:** I have a question for you.

**John:** Please.

**Craig:** And it’s off the beaten path entirely of what you’re saying, but it’s not, it’s related. Have you ever done the Myers-Briggs personality inventory thing?

**John:** Of course I’ve done the Myers-Briggs. Come on! A test that shows me why I am the way that I am? Yes.

**Craig:** [laughs] Now, what did you come out as?

**John:** I think I was an ENTJ.

**Craig:** ENTJ?

**John:** Which at the time I wouldn’t have guessed I was an extrovert, but the last 20 years I’ve become much more extroverted.

**Craig:** Yeah, I wouldn’t, I mean, it’s a funny thing, like, introvert/extrovert. I know this is a side topic. Because I used to qualify myself as an introvert but I think that was really a pose. Frankly, I’m incredibly extroverted. You know, the definition of introvert and extrovert is like: where do you get more jazzed from, interacting with people or being alone? And while I love being along and I enjoy being alone, I definitely get more jazzed being with people.

And the only reason I ask is because you have such a very specific… — Your approach to the world is very process-oriented. You have a specificity of process that is remarkable. Because most people just don’t have, [laughs], they don’t have such a — like the fact that you’ve got literally your folds and everything. And I was just wondering, like, where does that fit into that whole matrix?

**John:** Yeah. I think there is some process in there that comes up. It’s also just a matter, though, an experience of being in the meetings where I didn’t have those kind of notes and stumbling, like, “Argh.” And then you look over and you see Susan Shilliday who has all of these pages folded down and she’s having these great conversations. It’s like, “Oh, I’m going to do what she’s doing.”

So, really it’s observation and copying more than anything else. So, I picked up the meme of how you do those kinds of things. And a lot of what we do as screenwriters, I think, is observing, figuring out how it works, why it works, and then copying it in a way that is useful.

**Craig:** Oh, absolutely. In fact, I was talking about this with Todd Phillips the other day because the two of us are so, I mean, frankly we’re OCD, I think, about screenwriting. And because when we’re making changes on the set, you know, the guys who just come in, we block the scene out, we talk through some dialogue, we want to make some changes. When we make those changes we also change the action lines.

And that’s silly on one level because the guys have already come in and done it. There’s really no point to that. It really is about the dialogue at that point because they’ve already gone through the motions. They know what the motions are. They know where to stand, when to move, when to pick things up, and when to shoot a gun.

But we still fix it because we are obsessive and I actually feel like that level of obsession is important. I feel like if you don’t have it, I don’t know if you can be a good screenwriter. It seems part of the fabric of what we do.

**John:** Yeah. I do understand your point because really once you know what you’re going to do, you’re going to shoot it on film and the script is basically irrelevant at that point.

**Craig:** Right.

**John:** Like, yes, the editor may see it, but no one is ever really going to notice or care about that, but you will notice and care about that and you want the script to accurately reflect what you shot.

**Craig:** Yeah. I mean, to the point where we’re fudging things so we don’t spill over onto an A page, because we hate that. It’s just so weird.

**John:** [laughs] Yeah, but I get that, too.

So, for people who aren’t screenwriters who’ve gone through production, when you’re shooting a script you lock the pages. And by locking the pages that means if you need to change stuff you can just print out the new pages and they will slide in. And so page 88 will always be page 88.

But if you add too much to page 88 that it would spill over to page 89, instead of going to page 89 it goes to page 88A. And Craig and Todd do not want that to happen if they can possibly help it. And I completely understand.

**Craig:** Yeah, it’s annoying.

**John:** So, you will slightly cheat the margins on some dialogue blocks so that it won’t pop that next eighth of a page.

**Craig:** Oh, and see, and the funny thing is we also, [laughs], part of our obsession is that we refuse to do that. So, then we start, I mean, there have been times where the two of us have looked at each other and said, “You realize we’re now making the script worse because we don’t want an eighth of a page.”

**John:** That’s where you start removing the participle endings on verbs, so that things will shrink back down.

**Craig:** Or you start looking at your writing partner and you say things like, “Do we need this line? You know what, yeah, let’s not make the page break that makes us get rid of a line.” But, I don’t know, anyway, I’m sorry; I’ve taken us off into a crazy direction, but there’s something about the specificity of the way you were describing that just made me think — I’m loopy today, anyway. So, there you are.

**John:** Yeah, on Big Fish it really is actually important because we’re continually updating the script, and so if we do change something in staging I have to immediately change it in the script, and we have to change it in the score because it has to always match exactly because we are doing it again night, after night, after night, and with completely different people. And so theoretically we are creating these two documents, a script and a score, that anyone should be able to take and mount the musical.

And so it has been really strange where, you know, I’m like, “Well, I like the page the way it is, but I do need to change it now because it doesn’t accurately reflect what Edward is doing at that moment.” It’s been really interesting and strange to see how that works.

**Craig:** Yup.

**John:** And so when we were going through the workshop I was printing new pages all the time and every day we were having to put out revisions for things that were really trivial, like most people in the ensemble would have no idea why we were changing it, but we were changing it because it more accurately reflects what we’re actually doing.

**Craig:** Exactly. Yeah, OCD.

**John:** OCD.

The next thing I want to talk about is sort of an industry thing, which is one-step deals. And so, I can describe one-step deals, do you want to describe one-step deals? I mean, I feel like…

**Craig:** Yeah. It’s a short — a quickie description — when we get hired by a studio to write a script they basically hire you to write a draft. And you’re commenced on the draft, you write the draft, you turn the draft in, and that’s called a step.

When I started working, when John started working, traditionally you were hired to do two steps, so that’s two guaranteed steps. You write a draft, you turn it in. They give you notes, you write another draft, you turn it in. And they must pay you for those two drafts.

Then there are optional steps where after those two drafts if they still want you to work on stuff there is pre-negotiated fees and each one of those options is essentially the studio can or cannot engage them. And they are also pending your availability.

What happened about, I would say six years ago it really started to crop up in a big way, was that the studios started doing away with the second guaranteed step. Suddenly they were doing one-step deals where you were hired and you only had one guaranteed step. So, after you turn your first draft in they can say, “Bye. And we’re not paying you for…,” and the second step became optional suddenly.

And the Writers Guild Collective Bargaining Agreement doesn’t guarantee you anything more than a minimum of one step. And so the studios went from this over-scale two-step guarantee down largely to a one-step thing. And that’s where we are today.

**John:** So, I will pretend to be the studio person who is defending or arguing for why one-step deals are a good thing, which is not my actual belief, but I will try to express it.

So, one-step deals are good because if a writer delivers a terrible draft we’re not stuck with that writer for a second draft. And we can move onto a new writer. Or, sometimes we just decide, “You know what, we don’t really want to make this movie so we’re not wasting any more of our money or our time on this project that we don’t even want anymore.” And so it’s a way for us to maximize our development budget by not spending any more for a script than we really want to spend. And maximizing our development time by focusing on projects we really want to make and not the projects that we’ve now lost interest in.

**Craig:** And, you know, that’s a perfectly good argument and I think it actually applies fairly well to writers who make a lot of money. I understand it. Where my rebuttal to you, studio executive guy, would turn on newer writers who are not making a lot of money. By limiting these newer writers to one-step, first of all, you’re not saving that much money because they don’t make that much money, and the second step is less than the first step normally. And also, I should add, that agencies typically add a little extra onto the one-step because it’s only one-step.

So, the amount of money you’re saving is trivial to you and your development budget is $100,000 for the first step and $60,000 for the second step. The $60,000 is not going to change your life. That’s about as cheap as a draft can be in this world.

The bigger problem for you when you limit everything to one-step is this, Mr. Studio Executive: You have ceded all control to your producers. The producer — knowing now that they only have one shot because there’s only one draft that’s going to be turned in and they don’t make money unless the movie gets made — will grind that writer down to a nub. They won’t just write one script. They’ll have to probably write three or four drafts for this producer who is obsessive about polishing this thing to a shine before they turn it in, because they only get one shot.

And while you may say, “Who cares? Not my problem. That’s the writer’s problem,” it is your problem. Because the producer is now overdeveloping this material, likely in a way you wouldn’t even like. So, what you’re getting is an overworked, committee-ized piece of crap. That’s problem number one for you.

Problem number two — and now Mr. Studio Executive I’m going to ask you to do something that you don’t like doing. I’m going to ask you to look into the future and I’m going to ask you to think long term now, not about today or tomorrow even though you’re worried you might not be in your job in a year, think about five or ten years from now. Part of the job of screenwriting is learning how to deal with studio notes. We write a draft, we turn it in. We get studio notes from people like you, sir, and then we engage in a dialogue and hopefully come up with a synthesis that results in a second draft that everybody likes.

If you take that away as a routine part of our job, no one is going to really learn how to do that part of the job very well. There are writers out there who are suffering because your method of employing them doesn’t let them learn how to do the job properly. Who will be the people writing your movies five or ten years from now if all you do is burn through a succession of people, giving them one step and yanking it away?

My argument to you is: stick with one-step deals on people who are making a lot of money per step. I get it. But if you’re dealing with people who are making close to scale, it’s frankly unconscionable. They end up working on so many drafts that they’re far below scale per draft when all is said and done. And they don’t even get a chance to do anything new.

Oh my gosh, I just came up with another problem for you, Mr. Studio Executive. All the writers that are doing one-step deals, because it’s only one step, you know what they’re doing while they’re writing your script? Looking for their next job. So, now you have an employee with divided attention. And you know how you guys have made it really, really hard to get jobs? So while they’re writing your one draft they’re also doing pre-writes for their next potential job.

It’s a big mess.

**John:** So, again, I’m still a studio executive guy. So, here’s what I like about one-step deals. I know that writer is going to work his ass off because he only gets the one shot. I’m sick of writers who are not delivering on the first draft. Well, you know what? They better deliver because otherwise they’re not going to get their second step. So, when I gave these writers second steps, do you know what they would do? They would sort of lollygag. They would take their time because they knew there was more money coming.

Now they don’t know there is more money coming. They know that this is their one shot and they better write a damn good draft or else, tough, hit the road.

Now, listen, there are times where I am going to, you know, we’re going to read the script and like the script may be close — it might not be exactly what we want but we can see what the movie is, and then we’ll obviously go onto the writer’s second step. We do that all the time.

So, for you to say like, “Oh, the producer is grinding him down,” well maybe that’s good, and maybe the person is learning a lot from all that experience of working on the script.

But what you’re talking about, like the writers are going to be looking for their next job? They’re doing that anyway. I get so sick of when I find out writers are reading books for other people, or going to other pitches on stuff, when I know that I have them. They should be writing my movie. So, that’s already happening, Craig.

**Craig:** That’s happening, but not quite under the compressed time scale. I mean, you can’t have it both ways, Mr. Studio Executive. I mean, either writers are working hard on your stuff in a compressed one-step manner, or they’re doing it in the same lollygagging pace as two steps. And if it’s compressed and they’re working really, really hard, then yeah, I do think then going out to find other things is going to impact their lives.

I should also point out that when you say they’re going to work really, really hard to give you a script that you like, what they’re going to do is work really, really hard to give you a script you like. They’re going to deliver the safest, most expected thing possible because they only have one shot.

What I guarantee you they won’t do is surprise you. They certainly won’t exceed your expectations because they can’t afford to. They’re going to have to deliver the safest possible thing. And if that’s what you want, that’s what you want. But I got to tell you: you look at the movies that do well, you’ll never be surprised by anything. You’ll never get that new franchise; you’ll just get the expected old same old, same old.

**John:** You know who I like to work with? I like to work with writer-producers. I like to work with the guys who, some of them came out of TV, they’re people who write but they also produce, because I can talk to them, and they have professionalism. And I can tell them what I need and they will tell me when they’re going to hand it in and it’s going to work.

Those are the people I like to work with. And I don’t know why there aren’t more people like that.

**Craig:** I don’t know why there aren’t more people like that either. I’d like to be that way myself. That’s how I view myself. It’s possible — I’m just thinking about some of the writer-producers I know, that all of them came of age in the era of two-step deals, when they learned how to deal with things. [laughs] And they learned what was real. And they were allowed to fall, and stumble a little bit and get up, because they were trusted. It’s hard to give trust when you don’t have trust.

It’s hard to work in an environment where you’re told ahead of time, “We don’t think that you’re going to make it.” So, if you want to engender trust, and you want to have people that understand how the process works, perhaps let them engage in the process past the point of one mistake, or one failure, or one trip or stumble. Certainly they won’t come back to you.

And when they do succeed other people will be knocking on their door. Why would they answer you and your call when somebody else who has trusted them is saying, “Yeah, we always trusted you. Come stay here.”

**John:** So, I’m going to resume being John August here again. My experience with one-step deals has not been great. I’ve done very, very few of them. And when I took my first one I had sort of heard all the standard warnings. And I was like, “Oh no, it will be fine because I like the people involved; it’s all going to work out great.”

And it didn’t work out great. And what ended up happening, which is I think what happens under most one-step deals, is it’s not really one step. You’re essentially writing, and you’re writing, and you’re writing, and you’re writing to please the person who you’re directly dealing with. And at a certain point you’re like, “Okay, you know, it’s done.”

And they would say, “No, no, but remember, we only get one crack to go into the studio, so let’s just keep working on it, let’s keep working on it.” Like, “Okay, I’ll do a little bit more, I’ll keep working, we’ve got this one step. I want to make you happy.” Because writers, we want to make people happy.

But eventually it comes to this point where it’s like it’s been six months and so I’m saying, and now my agent is on the phone with the producers, and we’re saying, “We have to turn this in.” It essentially becomes a situation where you just never deliver. And you’re pretty confident that the studio has actually kind of already seen it and they’re really sort of getting extra work out of you.

And what’s happened is you have poisoned this relationship that you had with these producers who you liked otherwise, but all your enthusiasm for the project has died because you’re writing to please this phantom studio who you don’t even know what they actually really want.

If I’d been able to hand in that script when I was supposed to hand in that script we could have said like, “You know what, is this the movie that we all want to make? If it’s not, let’s have a conversation and see if there’s another movie that we all want to make.” But because we never actually turn it in, it becomes this mess.

And so that’s my experience as an A-list writer. But it’s that way, I think, kind of for everyone working on these projects. You never deliver.

**Craig:** Yeah. That’s the point. I mean, that’s why they do it. They’re trying to game the system. And even in your very accurate impression of a studio executive you’re cutting right to what they’re saying, “We trying to game the system. We’re figuring out a way where we can save money in the expectation of failure,” which is very corporate and classic risk management. And, you know, I don’t begrudge them their risk management, except for this: They’re in the wrong business if they think they can game risk. This is Hollywood. We’re not here to grind out 4% return on investment.

It’s show business and we’re gambling. And we’re gambling to try and find those breakout hits that cost $30 million to make $500 million. Or even we’re gambling on the big budget that’s $200 million that we think is going to make $500 million. This isn’t safe stuff where you’re, I don’t know, you’re pre-selling foreign so you cover your negative costs and the rest is gravy.

Get out of the business if you can’t handle a little bit of risk. And what they do is they try and eliminate risk by saying, “We presume you’ll fail. We don’t like writers anyway. We don’t trust any of you. You’re all lazy, so one step, and we’ll yank it from you. But we won’t really yank it from you because we know that the producer, who we may or may not even like, doesn’t get paid a dime unless this thing gets produced, so they’re going to work you. And we’ll see what we get. And if we like it we like it, and if we don’t we don’t. Really all we’re doing is trying to get a star to sign on, and then a director, and then we have a movie, and then we’ll hire a real writer to do it.”

**John:** Yup. And that rewriter…

**Craig:** It’s a recipe for disaster as far as I’m concerned.

**John:** Yeah, and that rewriter might be the writer-producer or someone else who comes in, like the finisher. And when I hear that discussion I really do think TV showrunners, that that person that the studio trusts to be able to deliver them the thing that they need to deliver. And that’s why I keep coming back, I think we’ve talked about this before: It’s frustrating that there’s not a feature equivalent of like the showrunner training program that the WGA has that teaches TV writers who are about to take over and run their own show sort of how to run your own show, which is this uniquely weird thing.

And I feel like the feature screenwriters who are getting movies into production who are doing that big giant tent pole work, that is a unique special thing, and I think we need to find a way to sort of teach people how to do that job and how to do the best version of that.

**Craig:** Well, this is where I have to kind of be guilty because, you know, Todd Amorde, who is one of our excellent Member Services people at the Writers Guild, has talked to me and to Billy Ray about creating that very thing. And I’ve been sort of after it for years.

And just the past few months I’ve been incredibly busy and I just haven’t had the time, I don’t know. And it’s been a little bit of a struggle to try and figure out how to structure it. So, maybe you and I can do this as a little side task and figure out how to structure a proper screenwriting training program, because I know it’s something the Guild wants to do.

And what I do do is every year…

**John:** You said “dodo.”

**Craig:** I said “dodo?” Yeah, I know. What I [laughs] — You know, this is one of the most human moments from you. It’s so unexpected when you’re immature. I love it. It makes me happy, it does. Because I always feel like I’m the goof, you know.

So, what I do do is once a year I do a basically two-hour seminar on surviving and thriving in development and production as a screenwriter. And it’s really about strategies. It’s not about the writing at all. It’s about dealing with people, notes, process, doing it in such a way that you actually — that your position as the writer improves through the process rather than when it normally degrades.

And that’s been very successful. I’m going to do it again, I think, in March. But you and I should talk about how to do a screenwriting training program.

**John:** It occurs to me that the different thing about the TV showrunners program is it’s really clear, like, “is this person going to be running a show?” and therefore like, “Okay, well then they’re in.” And the litmus test for sort of who-do-you-actually-pick-to-be-as-part-of-this-program is a little bit trickier.

My first thought, and I may reject this thought, is that you should actually just ask the studios, like, “Who do you want to see go through this program?” Because in a weird way they kind of know who they feel like is going to be those writers who they want to sort of go through there. And those are the people they may want — they may already have their eye on, like, “These are the young women and men who we feel are going to be the next batch of writers we’re going to be going to for this production work. And we want these people to go through it.” I don’t know.

**Craig:** It’s not a bad thought. I think that…

**John:** If you got studio buy-in I think it would be helpful.

**Craig:** The other challenge beyond the criteria for who participates is the television showrunner program has certain nuts and bolt stuff that really can be taught. How to hire a staff. How to deal with the fact that writers are now your employees. How do you fire them. How do you deal with assigning tasks to a room. How do you work as a go between. How do you deal with actor deals and casting.

There is so much going on. And for screenwriting there’s a bit less, but sometimes I feel like it’s almost trickier because we don’t have that producing title, typically. And yet I believe that if a screenwriter does her job correct she could be as powerful as, if not more powerful than, the actual producer.

**John:** Yeah. Yeah. The topics are, you know, they are different, because you’re not going through casting. You’re not going through some of the other things that you would normally be going through. But it’s very much — it tends to be more anecdotal. I think you’d have to be bringing in a bunch of other screenwriters to talk through, “These are the scenarios I’ve commonly found. This is how you deal with the situation where the big, the A-list actor has brought you in on the project but the director really doesn’t want you there, and how do you negotiate that?”

Or, “There’s a conflict between the studio and the director and you are supposed to somehow bridge this impossible divide.”

**Craig:** Right.

**John:** That’s the kind of stuff that you need to know how to deal. And while it can’t be taught I think it can be shared.

**Craig:** Well, you know, that’s a great idea right off the bat for a portion of this training would be “man in the middle.” How do you deal with being — because you are so right. And frankly being able to triangulate yourself is a very powerful thing to do. You become incredibly useful beyond the work that you’re doing. And frankly, I hate to say it, but it’s important. It’s not enough to write well; you need to be indispensable beyond that.

Because a lot of times nobody really knows what good writing is. Not always, but a lot of times. A lot of times what keeps you around, and what keeps you engaged in your primary mission which is to write the best movie you can, is to be indispensable in other ways as well. So, that’s a good idea for a class.

**John:** Great. Well, let’s move on and talk about a very big movie that John Logan wrote called Skyfall, which you just recently saw, and I saw like two weeks ago.

**Craig:** [sings] Let the Skyfall, when it crumbles…

**John:** [sings] Let the Skyfall.

So, I really enjoyed the movie. Sam Mendes directed it. Sam Mendes was supposed to direct Preacher and then he left Preacher to do the Bond movie. I’m like, “Well that’s a giant mistake because the Preacher movie is going to be awesome.” But you know what? The Bond movie was really, really good. I really enjoyed it. Did you enjoy the movie, Craig?

**Craig:** I did enjoy it. I guess I should ask first before I go into it: Are you a — I’m a big Bond fan. I love Bond movies. What about you?

**John:** I’m a big Bond fan, too. And I grew up with, especially the — for whatever reason the Sunday night before school started in the fall there was always a Bond movie on ABC. And so that was really my exposure to Bond was watching the ABC cuts of them.

So, the Spy Who Loved Me is sort of my entryway to it. So, my first Bond movies were the Roger Moore’s but then I did go back through and got all my Sean Connery’s and Lazenby’s. And so I think I’ve seen all of them.

**Craig:** Yeah. As have I. And very typical for guys our age to have started with the Roger Moore and then go backwards to Sean Connery.

I thought that it was a very successful Bond movie. I’ll talk about what I didn’t like, because it’s a smaller portion, and then I’m going to talk about what I really liked.

**John:** And let’s just put a spoiler warning here.

**Craig:** Oh spoilers. Yes.

**John:** We’re going to have some general spoilers here. So, don’t — you can skip ahead if you’ve not seen the movie.

**Craig:** Yeah, I won’t give away too much. I’m just going to say I really enjoyed the character of the villain. It was a bit reminiscent of Sean Bean’s character from GoldenEye, the sort of disgraced former agent come back as a baddie. I did not like his plot. Even for Bond plots it was nonsensical.

I understood his goal. I understood his motivation. I just didn’t understand his method. It was bizarre and it existed solely to service set pieces, which were very good set pieces.

**John:** Yeah. It was the problem of, like, somebody who has a nuclear device and they’re using it to rob a bank. It just doesn’t — the scale of what he was able to do didn’t make sense with what he was actually trying to do. And, granted, that’s actually kind of a trope of the Bond movies overall, but I felt like if he had this personal vendetta he had many better ways to enact his personal vendetta. And we didn’t need — all the set pieces were kind of irrelevant for that.

That said, it was a Bond movie, so you cut it this giant bit of slack because that’s how these movies work.

**Craig:** I agree. I agree. There’s an element of camp to it and you forgive some of the Rube Goldbergian nonsense.

Here’s what I loved about this Bond movie. First, I loved — and maybe primarily — I loved the theme. And actually Bond movies typically are theme-less. This is something that I’ve got to tip my hat to Nolan, because I feel like Christopher Nolan has revived an interest in proper theme in big action movies. And the theme here is articulated by Albert Finney towards the end when he says, “Sometimes the old ways are best.”

And this movie was very much about the old ways and about the old Bond, and the notion that while we could sort of go on and chase the people that exist because of us, like say the Bourne franchise, which is sort of hyper-realistic, we’re not going to. You know what? We’re going to go be ridiculous Bond because that’s what we are. And ridiculous Bond is old school. He himself is dealing with aging issues. M is dealing with aging issues. The entire spirit of MI6 is called is called into question as being antiquated.

You have this new Q who is essentially putting down the entire thing as ridiculous and something that he could do from his bedroom. And so thematically the whole movie held together on a thematic level better than practically any Bond I’ve ever seen.

There were some great retro set pieces. The Komodo Dragon fight was like right out of the ’60s. I loved it. And the last scene where he walks into that classic office with the leather door and Ralph Fiennes now as M — boy, really into spoilers here — and Moneypenny.

And you know what I have to say, [laughs], and again I always feel like I get in trouble by being sexist, I just somehow, I was, like, how brave of them oddly to just embrace and not worry about people going, “Oh, it’s sexist.” Yes, of course, Bond is sexist. It’s a sexist franchise. It’s porn for men without boobies. Sometimes it has boobies.

But, there’s a female secretary that’s hot for him. And there’s a man in stuffy leather office who gives him assignments. And he goes and does it. And I love that. I just thought it was great and I’m very excited for the next one because of that.

**John:** I think the Christopher Nolan Batman movies is a good reference for it, because I think what it did, like the Nolan movies, is it took the irreducible elements of what James Bond is and rearranged them in a way that could make a new movie. And you’re not really aware of it through a lot of it. It just seemed like a really good, like a much better, more competent Bond movie. And then you get to that bizarre fourth act, which really is a fourth act.

The movie kind of should have stopped at London when the villain’s plot was foiled, and then we go onto Scotland and to all this new stuff, and all this back story which doesn’t really exist, in the film canon at least.

And we have this completely different movie that’s happening there and yet it feels kind of right. And we’re burning down the right things. We’ve already destroyed MI6. Now we’re destroying his history. We’re destroying his car. We’re destroying his mother, or his mother figure. We’re introducing Albert Finney who is just some other person who is sort of representing Sean Connery, I think, from the original franchise.

**Craig:** They even thought about casting Sean Connery.

**John:** Yeah, so I just really enjoyed what they were able to do. And it was one of those rare situations where you leave a movie excited for where it puts you next.

**Craig:** Exactly. Exactly. In the way that — by the way, Casino Royale excited me. Because I thought Daniel Craig did such a great job, and that movie was really good. It was a really good Bond movie and I loved the physicality of it and the way that it updated it without losing its connection to old Bond-ness.

And then because of the issues involving MGM, they just weren’t able to capitalize on that wonderful start that Casino Royale had. And I feel like with this one they’re back on track and they’re set up for a great next movie.

And by the way, one other thing I should mention about the canonical issues, there was an interesting essay — and this is total Bond nerd stuff — but there had been this kind of debate. The question is: Is James Bond actually James Bond’s name? Or is that a code name that agents use, and in part would explain why there continually are new James Bonds?

And this movie sort of says, no, no, his name is James Bond. And you just are meant to understand that there are different people playing him.

**John:** Yeah. It’s almost the “no one recognized Bruce Wayne is Batman.”

**Craig:** Right. You just go with it and that’s that.

**John:** That’s part of the premise.

**Craig:** Yeah. I really liked it. And I do think that Skyfall, the theme song, is a really good song. It’s really good. And, you know, the wonderful tradition of great Bond theme songs, and we’d lost it. You know, we had lost it for so long. Bond songs were hits. And this is the first one in forever that’s a real hit.

**John:** So, I taught myself to play it on the piano. And it’s actually very simple, and it goes through the classic sort of it’s in A-minor, it goes through the classic sort of Bond chords in a very smart way to use it. But I did find it actually mashes in really well with For Your Eyes Only. Because For Your Eyes Only goes down to a single note, and if you transpose it so that single note is the [sings] “da-da-da-da,” and you can guild it back out to this.

So, it’s a really great song and it just made me happy for Bond themes again.

**Craig:** Yeah, it was great also in that moment where they pull the Aston Martin out to go back to the classic — or actually I think it was the moment where they blew up the car where you had the classic, [sings classic Bond theme], which I love, you know. And I love the way that Skyfall worked that theme in of the [sings classic Bond theme], that little chromatic thing that they do.

And it’s a great song. And even the lyrics are terrific.

**John:** Yeah. Adele’s, sort of marbles-in-her-mouth sometimes bugs me a little bit, more so than many other songs I sort of felt that, and yet I did kind of love it all the same.

**Craig:** I don’t recognize that she has marble mouth. Give me an example of marble mouth.

**John:** Marble mouth is just so weird. There are some words where it’s like if you didn’t really kind of know what she was saying, it’s like, “What word are you making there?”

**Craig:** Eh, yeah. Well, you know, singers sometimes change vowels to make it sound prettier. But, you know, I just like that Skyfall is where it starts. “Skyfall is where we start. A thousand miles and poles apart.” And just the whole idea of the crumbling down and Skyfall is where we…

**John:** Yeah. It’s the romance of apocalypse, which is great.

So, from that exciting news, we should get to our One Cool Things. I know your One Cool Thing is not actually cool at all, but it’s…

**Craig:** Well, there’s a cool part to it.

**John:** All right, so you go first.

**Craig:** Okay. Well, it’s One Tragic Thing. Don Rhymer died this morning at 3:30am. You know, when you guys listen to the podcast it will be probably a week later.

Don was a screenwriter and television writer. He worked from pretty much the second he landed foot in Los Angeles all up until maybe two months ago when he was just too sick to go on. He’s written — everything he wrote on, sitcoms like Evening Shade; he wrote big huge hit movies like Rio. And he was my friend, he was neighbor, he was my officemate. We shared an office for awhile and then I got the office next to his.

So, even now his office is next to me. Obviously the lights are out and he’s not coming back. And he battled cancer for years. And I’m saying this in part because he was my friend and I loved him and I miss him, and you want to talk about that when somebody that you care for dies. But there’s something instructive about it, too, and something good. And that is that Don lived a great screenwriting life, and if that sounds a little odd all I can say is he took the worst this town can dole out, and it doles out some tough stuff.

I mean, he was knocked around by some of the meanest and most ridiculous in this business, and he never fell down and he kept on coming. And he was the same way when he got cancer. Just indomitable and wouldn’t back down and wouldn’t quit. Nose to the grindstone. A true professional.

And we sometimes feel as if we feel we have the right to be precious about what we do. And I guess we do have that right, but when you have a family, and when you have kids, and a wife, and you need to provide for their future, you also have an obligation to them. And Don never forgot that. And he was a professional — a professional’s professional. And I’d like to think that I could have the kind of career and continue the way he did.

Never once did Don ever say, “This job is beneath me.” Never once did he ever say, “I’m too good to work.” Never once did he question anything. You got the feeling that they couldn’t get rid of Don if they tried. And not that they ever did.

I will miss him greatly, and once I hear from his family I’m sure there will be a charity that they’re going to ask donations to go to in lieu of flowers and that sort of thing. And once I have that information I will get it to you and you can put it online.

And I know he listened to the podcast, too. So, goodbye Don. I’ll miss you.

**John:** I never had a chance to — I think the only time I really had a chance to talk with him was at Christmas parties, and sort of like other sort of social gatherings of screenwriters. And when I found he had cancer, Don started a blog about his cancer treatments called Let’s Radiate Don. And so I’ll put a link up to that because it’s really funny. And you wouldn’t think that going through lots of chemotherapy and different surgeries would be funny, but he managed to make it really funny.

And so over the time he was getting treatment we had several emails back and forth and I just talked about how much I dug what he was doing. And I kept wishing him the best.

**Craig:** Yeah. That blog is sort of an example. I mean, the guy was a writer. And when you’re a writer you will write through anything. It’s your way of processing the world and your way of understanding what’s even happening to you. And I guarantee you that there were days when Don was in pain or nauseated or in despair and he was taking his time in his OCD way, the way you and I are, to edit those posts before sending them out, just to polish them off.

**John:** To find the funny and make sure…

**Craig:** Yeah. And that to me, that’s so honorable. It’s just there’s an honor, I think, in doing this kind of work if you do the work. And he lived that way. And so my hat’s off to him.

**John:** Well, Craig, thank you very much for a good podcast. Sorry to end it on a sad but also kind of hopeful note.

**Craig:** Yeah. And hopefully no one else will die within the next week.

**John:** Yes, that would be a very good thing. So, thanks so much and I will talk to you next week. Bye.

**Craig:** See you next time. Bye.