![]() If a main part of a plot is that two characters look identical (but are not related…think the movie “Dave”), where/how in the script do I say they should be played by the same actor?

If a main part of a plot is that two characters look identical (but are not related…think the movie “Dave”), where/how in the script do I say they should be played by the same actor?

— Jeremy Kerr

As a general screenwriting rule, if it would be obvious to the viewer, make it obvious to the reader. Immediately after introducing the second character, include a hard-to-miss note explaining that the two characters are played by one actor.

PROFESSOR DONALD SCOTT isn’t your classic tweedy bookworm. With a short temper and a strong right hook, he’s more likely to settle arguments in back alleys than lecture halls.

[NOTE: Donald Scott and Thom Penn aren’t twins, but are played by the same actor -- for reasons that will soon become clear.]

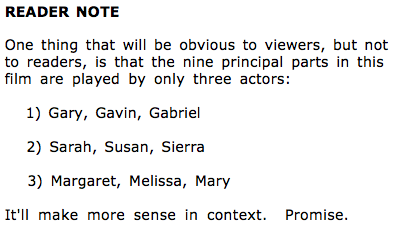

In the case of The Nines, a huge conceit was that the nine principal roles were played by three actors. I added a note just after the title page, so there was no chance a reader would miss it: