![]() I’ve searched through The Hollywood Standard and most of your site’s scripts, and nothing pings for “WRITER’S NOTE.” Does that mean they don’t really exist or should never be used?

I’ve searched through The Hollywood Standard and most of your site’s scripts, and nothing pings for “WRITER’S NOTE.” Does that mean they don’t really exist or should never be used?

If they can be used, what would you suggest as a way to format instances where the screenwriter wants to stop and point something out that helps the readers read? Even saying that makes it sound like you shouldn’t do it, but I swear I’ve seen them used before…even though I can’t find any examples now.

— Steve Maddern

![]() In most cases, you can handle things like this in scene description. For example, if you have a recall of a character we haven’t seen in a long time:

In most cases, you can handle things like this in scene description. For example, if you have a recall of a character we haven’t seen in a long time:

Durban’s massive Henchman -- the same one we saw in the opening sequence -- emerges from wreckage, cut and bruised but somehow still alive.

Or to describe how a sequence is meant to be shot:

In a dreamy, super-saturated haze, Celia makes her way through the crowded party, a grin stretched ear-to-ear. She is floating, with TEENAGERS rushing past her.

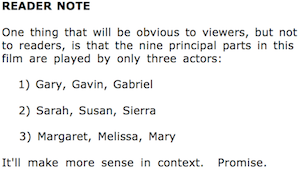

Only very rarely do you have to do a full dead stop to explain something to readers. I’ve probably done it twice in 40+ scripts. For The Nines, I have a note to readers right after the title page:

But that’s a really odd case.

You’ll almost always be able to handle it in-line with scene description. Set it off with parentheses, brackets or dashes if it helps. But there’s no need to label it as a writer’s note or somesuch.