Loglines are one-or-two sentence summaries of a story or screenplay. Here’s an example:

– When a prize-winning journalist makes up a source, she pays an ex-con to be her supposed poet-laureate.

That’s a logline I wrote for Sam Hamm’s 1988 script “Pulitzer Prize.” It’s likely the first logline I ever wrote, way back in film school. We were learning how to write coverage, the industry-standard reports that studios and producers use when considering projects.

I ended up working as a paid reader for a little over a year, writing coverage for Tri-Star Pictures. On the top sheet of every piece of coverage I turned in, I had to write a logline. Here are more examples from that time:

– A long-suffering percussionist becomes the director of a dismal marching band.

– An avalanche traps a family in their house, along with a stranger who may be a killer.

– Writing a story about a lonely rancher, a New York Times reporter falls in love with her subject.

– Left home alone for the holidays, James Bond’s nephew uncovers gold thieves.

These feel like the summaries you’d see in TV Guide or on Netflix. They’re short, just enough to give a sense of the project.

Once I stopped working as a reader, I never wrote another logline. It’s just not a thing I’ve ever needed to do as a professional screenwriter.

But *aspiring* screenwriters sometimes do find themselves writing loglines, particularly when submitting material to competitions. ((Screenwriting competitions are often a waste of time, as we’ve discussed often on the show.)) So they’re worth discussing.

Luckily, a reader has spent a lot of time digging into loglines. Viðar Freyr Guðmundsson writes:

> I went through the transcripts of your shows to find that you are in fact not huge fans of the concept of loglines. With my limited experience, I tend to agree. It seems counter intuitive for many types of stories to summarize them in a sentence or two.

> There seems to be a dogmatic view, however in the community of screenwriters regarding this issue. It is that there is a certain formula for the perfect logline. The formula stated is as follows:

> “When (inciting incident), (hero) struggles against (antagonistic force) in order to (goal) before (stakes are lost).”

My first logline basically fits this pattern, but notably none of the others do. Still, this *feels* right. Most stories and most loglines are going to have these elements.

There’s going to be a hero or group of heroes. The logline might shorthand this by using a location or setting. “A theme park” or “a space merchant vessel” suggests that the staff/crew/guests are the main characters.

Likewise, every story is going to have some central dilemma or conflict that serves as the antagonistic force. For the logline, that’s often implied by the setup.

– When her frozen eggs are stolen, a glamorous movie star must scramble to get them back in time.

This logline doesn’t say that the egg thief is the antagonist, but it’s a reasonable assumption.

Guðmundsson continues:

> I was curious to find if the best loglines, of the movies we all know, do in fact follow this template to a degree. So I went through the ‘101 Best Movie Loglines Screenwriters Can Learn From’ as chosen by Ken Miyamoto of Screencraft. My aim was to identify these key features of an ideal logline.

Here’s how often Miyamoto’s loglines included specific elements:

| Element | Frequency |

|——————-|———-:|

| Hero | 100% |

| Inciting Incident | 86% |

| Antagonist Force | 81% |

| Goal | 66% |

| Stakes | 19% |

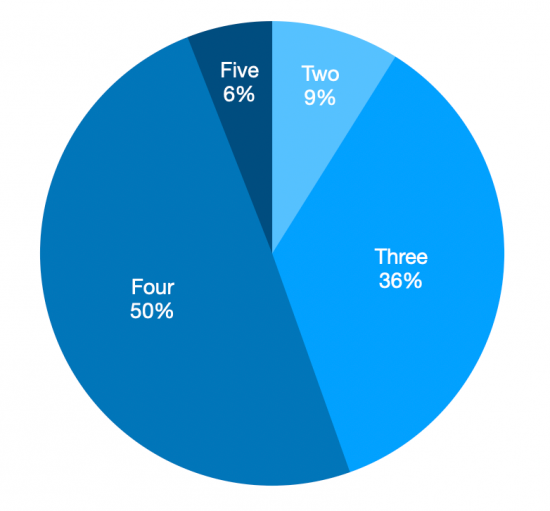

Guðmundsson found that the overwhelming majority of loglines have either three or four of the elements, while very few (6%) seem to follow the formula completely.

> A common pattern of deviation seems to be that there is either no goal or no antagonistic force. Perhaps these are somewhat interchangeable.

Here’s a look at how many loglines had two or more elements:

### Takeaways

Do loglines matter? After all, they aren’t something screenwriters are paid to write, nor are they meant to sell someone on an idea like a pitch.

Having written a lot of loglines as a reader, I’m mindful that several of my films are difficult to reduce to a sentence including Go, Big Fish and The Nines. God help whatever reader had to write coverage on them.

Loglines aren’t plot or story. At most, they’re arrows pointing towards story. As you can see in Guðmundsson’s markup of the Miyamoto loglines, you wouldn’t know quite what movie you’re getting based on a single sentence.

### One Hundred and One Loglines

These are from [Screencraft](https://screencraft.org/2019/07/29/101-best-movie-loglines-screenwriters-can-learn-from/), with highlighting by Guðmundsson. Here’s the template:

When (inciting incident), (hero) struggles against (antagonistic force) in order to (goal) before (stakes are lost).

- The aging patriarch of an organized crime dynasty transfers control of his clandestine empire to his reluctant son.

- After a simple jewelry heist goes terribly wrong, the surviving criminals begin to suspect that one of them is a police informant.

- A depressed suburban father in a mid-life crisis decides to turn his hectic life around after becoming infatuated with his daughter’s attractive friend.

- A mentally unstable Vietnam war veteran works as a night-time taxi driver in New York City where the perceived decadence and sleaze feeds his urge for violent action, attempting to save a preadolescent prostitute in the process.

- With the help of a German bounty hunter, a freed slave sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner.

- During the U.S.-Vietnam War, Captain Willard is sent on a dangerous mission into Cambodia to assassinate a renegade colonel who has set himself up as a god among a local tribe.

- An aspiring author during the civil rights movement of the 1960s decides to write a book detailing the African-American maid’s point of view on the white families for which they work, and the hardships they go through on a daily basis.

- Two imprisoned men bond over a number of years, finding solace and eventual redemption through acts of common decency.

- A Las Vegas-set comedy centered around three groomsmen who lose their about-to-be-wed buddy during their drunken misadventures then must retrace their steps in order to find him.

- A cop has to talk down a bank robber after the criminal’s perfect heist spirals into a hostage situation.

- young F.B.I. cadet must confide in an incarcerated and manipulative killer to receive his help on catching another serial killer who skins his victims.

- The lives of two mob hit men , a boxer, a gangster’s wife, and a pair of diner banditsintertwine in four tales of violence and redemption.

- A computer hacker learns from mysterious rebels about the true nature of his reality and his role in the war against its controllers.

- A wheelchair-bound photographer spies on his neighbors from his apartment window and becomes convinced one of them has committed murder.

- A quirky family determined to get their young daughter into the finals of a beauty pageant take a cross-country trip in their VW bus.

- A group of seven former college friends gathers for a weekend reunion at a South Carolina winter house after the funeral of one of their friends.

- A man creates a strange system to help him remember things so he can hunt for the murderer of his wife without his short-term memory loss being an obstacle.

- A thief who steals corporate secrets through the use of dream-sharing technology is given the inverse task of planting an idea into the mind of a CEO.

- When a teenage girl is possessed by a mysterious entity, her mother seeks the help of two priests to save her daughter.

- A fast-track lawyer can’t lie for 24 hours due to his son’s birthday wish after the lawyer turns his son down for the last time.

- An insomniac office worker and a devil-may-care soap maker form an underground fight club that evolves into something much, much more.

- Plagued by a series of apocal yptic v isions, a young husband and father questions whether to shelter his family from a comi ng st orm, or from himself.

- A nun , while comforting a convicted killer on death row , empathizes with both the killer and his victim’s families.

- A paraplegic marine dispatched to the moon Pandora on a unique mission becomes torn between following his orders and protecting the world he feels is his home.

- A seventeen-year-old aristocrat falls in love with a kind but poor artist aboard the luxurious, ill-fated R.M.S. Titanic.

- During a preview tour, a theme park suffers a major power breakdown that allows its cloned dinosaur exhibits to run amok.

- A Lion cub crown prince is tricked by a treacherous uncle into thinking he caused his father’s death and flees into exile in despair, only to learn in adulthood his identity and his responsibilities.

- After young Riley is uprooted from her Midwest life and moved to San Francisco, her emotions – Joy, Fear, Anger, Disgust and Sadness – conflict on how best to navigate a new city, house, and school.

- In a post-apocalyptic wasteland, a woman rebels against a tyrannical ruler in search for her homeland with the aid of a group of female prisoners, a psychotic worshiper, and a drifter named Max.

- A washed-up superhero actor attempts to revive his fading career by writing, directing, and starring in a Broadway production.

- In the Falangist Spain of 1944, the bookish young stepdaughter of a sadistic army officer escapes into an eerie but captivating fantasy world.

- A teenage girl raids a man’s home in order to expose him under suspicion that he is a pedophile.

- When their relationship turns sour, a couple undergoes a medical procedure to have each other erased from their memories.

- A troubled teenager is plagued by visions of a man in a large rabbit suit who manipulates him to commit a series of crimes after he narrowly escapes a bizarre accident.

- A self-indulgent and vain publishing magnate finds his privileged life upended after a vehicular accident with a resentful lover.

- A boy who communicates with spirits seeks the help of a disheartened child psychologist.

- Seventy-eight-year-old Carl Fredricksen travels to Paradise Falls in his home equipped with balloons, inadvertently taking a young stowaway.

- In order to power the city, monsters have to scare children so that they scream. However, the children are toxic to the monsters, and after a child gets through, two monsters realize things may not be what they think.

- When a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach community, it’s up to a local sheriff, a marine biologist, and an old seafarer to hunt the beast down.

- In the distant future, a small waste-collecting robot inadvertently embarks on a space journey that will ultimately decide the fate of mankind.

- A prince cursed to spend his days as a hideous monster sets out to regain his humanity by earning a young woman ‘s love.

- A hapless young Viking who aspires to hunt dragons becomes the unlikely friend of a young dragon himself and learns there may be more to the creatures than he assumed.

- Following the Normandy Landings, a group of U.S. soldiers goes behind enemy lines to retrieve a paratrooper whose brothers have been killed in action.

- A 17-year-old high school student is accidentally sent thirty years into the past in a time-traveling DeLorean invented by his close friend, a maverick scientist.

- A cowboy doll is profoundly threatened and jealous when a new spaceman figure supplants him as top toy in a boy’s room.

- A team of explorers travels through a wormhole in space in an attempt to ensure humanity’s survival.

- A former Roman General sets out to exact vengeance against the corrupt emperor who murdered his family and sent him into slavery.

- With his wife’s disappearance having become the focus of an intense media circus, a mansees the spotlight turned on him when it’s suspected that he may not be innocent.

- A young soldier in Vietnam faces a moral crisis when confronted with the horrors of war and the duality of man.

- A young janitor at M.I.T. has a gift for mathematics but needs help from a psychologist to find direction in his life.

- The lives of guards on Death Row are affected by one of their charges: a black man accused of child murder and rape, yet who has a mysterious gift.

- An undercover cop and a mole in the police attempt to identify each other while infiltrating an Irish gang in South Boston.

- After a young man is murdered, his spirit stays behind to warn his lover of impending danger, with the help of a reluctant psychic.

- In 1954, a U.S. Marshal investigates the disappearance of a murderer, who escaped from a hospital for the criminally insane.

- An insurance salesman discovers his whole life is actually a reality TV show.

- A small-time boxer gets a supremely rare chance to fight a heavy-weight champion in a bout in which he strives to go the distance for his self-respect.

- A criminal pleads insanity after getting into trouble again and once in the mental institution rebels against the oppressive nurse and rallies up the scared patients.

- A retired Old West gunslinger reluctantly takes on one last job, with the help of his old partner and a young man.

- A determined woman works with a hardened boxing trainer to become a professional.

- Two detectives, a rookie and a veteran, hunt a serial killer who uses the seven deadly sins as his motives.

- A working-class Italian-American bouncer becomes the driver of an African-American classical pianist on a tour of venues through the 1960s American South.

- An NYPD officer tries to save his wife and several others taken hostage by German terrorists during a Christmas party at the Nakatomi Plaza in Los Angeles.

- After a space merchant vessel perceives an unknown transmission as a distress call, its landing on the source moon finds one of the crew attacked by a mysterious lifeform, and they soon realize that its life cycle has merely begun.

- Violence and mayhem ensue after a hunter stumbles upon a drug deal gone wrong and more than two million dollars in cash near the Rio Grande.

- A weatherman finds himself inexplicably living the same day over and over again.

- After awakening from a four-year coma, a former assassin wreaks vengeance on the team of assassins who betrayed her.

- A group of professional bank robbers starts to feel the heat from police when they unknowingly leave a clue at their latest heist.

- As corruption grows in 1950s Los Angeles, three policemen — one strait-laced, one brutal, and one sleazy — investigate a series of murders with their own brand of justice.

- When an open-minded Jewish librarian and his son become victims of the Holocaust, he uses a perfect mixture of will, humor, and imagination to protect his son from the dangers around their camp.

- After discovering a mysterious artifact buried beneath the lunar surface, mankind sets off on a questto find its origins with help from intelligent supercomputer HAL 9000.

- A mother personally challenges the local authorities to solve her daughter’s murder when they fail to catch the culprit.

- After a tragic accident, two stage magicians engage in a battle to create the ultimate illusion while sacrificing everything they have to outwit each other.

- After the death of a friend, a writer recounts a boyhood journey to find the body of a missing boy.

- A family heads to an isolated hotel for the winter where a sinister presence influences the father into violence, while his psychic son sees horrific forebodings from both past and future.

- A tale of greed, deception, money, power, and murder occur between two best friends: a mafia enforcer and a casino executive, compete against each other over a gambling empire, and over a fast living and fast loving socialite.

- A seemingly indestructible android is sent from 2029 to 1984 to assassinate a waitress, whose unborn son will lead humanity in a war against the machines, while a soldier from that war is sent to protect her at all costs.

- A Phoenix secretary embezzles forty thousand dollars from her employer’s client, goes on the run, and checks into a remote motel run by a young man under the domination of his mother.

- A private detective hired to expose an adulterer finds himself caught up in a web of deceit, corruption, and murder.

- A sole survivor tells of the twisty events leading up to a horrific gun battle on a boat, which began when five criminals met at a seemingly random police lineup.

- Held captive for 7 years in an enclosed space, a woman and her young son finally gain their freedom, allowing the boy to experience the outside world for the first time.

- A research team in Antarctica is hunted by a shape-shifting alien that assumes the appearance of its victims.

- A New York City advertising executive goes on the run after being mistaken for a government agent by a group of foreign spies.

- A promising young drummer enrolls at a cut-throat music conservatory where his dreams of greatness are mentored by an instructor who will stop at nothing to realize a student’s potential.

- Allied prisoners of war plan for several hundred of their number to esc ape from a German camp during World War II.

- A former neo-nazi skinhead tries to prevent his younger brother from going down the same wrong path that he did.

- A young man and woman meet on a train in Europe and wind up spending one evening together in Vienna. Unfortunately, both know that this will probably be their only night together.

- A screenwriter develops a dangerous relationship with a faded film star determined to make a triumphant return.

- An angel is sent from Heaven to help a desperately frustrated businessman by showing himwhat life would have been like if he had never existed.

- A toon-hating detective is a cartoon rabbit‘s only hope to prove his innocence when he is accused of murder.

- Two 1990s teenage siblings find themselves in a 1950s sitcom, where their influence begins to profoundly change that complacent world.

- A young programmer is selected to participate in a ground-breaking experiment in synthetic intelligence by evaluating the human qualities of a highly advanced humanoid A.I.

- Two astronauts work together to survive after an accident leaves them stranded in space.

- An I.R.S. auditor suddenly finds himself the subject of narration only he can hear: narration that begins to affect his entire life, from his work, to his love-interest, to his death.

- The spirits of a deceased couple are harassed by an unbearable family that has moved into their home, and hire a malicious spirit to drive them out.

- A young African-American visits his white girlfriend’s parents for the weekend, where his simmering uneasiness about their reception of him eventually reaches a boiling point.

- A young couple moves into an apartment only to be surrounded by peculiar neighbors and occurrences. When the wife becomes mysteriously pregnant, paranoia over the safety of her unborn child begins to control her life.

- In a post-apocalyptic world, a family is forced to live in silence while hiding from monsters with ultra-sensitive hearing.

- The monstrous spirit of a slain janitor seeks revenge by invading the dreams of teenagerswhose parents were responsible for his untimely death.

- An eight-year-old troublemaker must protect his house from a pair of burglars when he is accidentally left home alone by his family during Christmas vacation.

- A man must struggle to travel home for Thanksgiving with an obnoxious slob of a shower curtain ring salesman as his only companion.

- A troubled child summons the courage to help a friendly alien escape Earth and return to his home world.

Big thanks to Dustin Bocks for his web wizardry getting this highlighting to work.