![]() I’m working on a series of web films that I fancy to self-produce and distribute through Youtube, etc. I’m curious: is there an easy (i.e. free) way to confirm I’m not stepping on anyone’s toes with the names I’ve chosen for characters, companies, products, etc in my story?

I’m working on a series of web films that I fancy to self-produce and distribute through Youtube, etc. I’m curious: is there an easy (i.e. free) way to confirm I’m not stepping on anyone’s toes with the names I’ve chosen for characters, companies, products, etc in my story?

I know there’re entire businesses dedicated to tracing and checking this information for those in the industry, but I’m limited to typing the names into Google and hoping no results appear.

Is this worth worrying about, and is there an easy way to go about it?

— Russell Gawthorpe

![]() What you’re talking about are called clearances. There are companies that do that for you (the [de Forest Report](http://www.deforestresearch.com/)™ is the best known), but for smaller projects it’s not hard to DIY.

What you’re talking about are called clearances. There are companies that do that for you (the [de Forest Report](http://www.deforestresearch.com/)™ is the best known), but for smaller projects it’s not hard to DIY.

As an intern at Universal, one of my assignments was handling clearances for the art department on the Kevin Costner film The War. They had a bunch of vintage signs, and my task was to figure out whether any of the brands or companies featured were still in business. This was pre-internet, so I ended up making a lot of phone calls.

When checking clearances, you’re hoping for one of two outcomes:

1. There’s nothing/no one with that name. You’re clear.

2. There are so many items or people with that name that no reasonable person would assume you’re talking about it/him specifically. ((But location and job might be a factor. “Bill Smith” is generic and ubiquitous, but if the character is a police sergeant in San Diego, and there is a real William Smith working for the police department there, you have an issue.))

But when you’re checking clearances, you often find yourself in a middle ground. There’s somebody or something with that name, or close enough to it that it might be a problem. If that happens, you can talk to the person and ask them to sign a clearance release. It’s a pretty generic “we won’t sue” form that your producer (or attorney) will provide.

In other cases, you’re presented with a logo or artwork that may or may not be someone’s trademark. To the degree possible, you avoid it. But a sizable percentage of clearances really come down to a judgment call: what are the odds someone has the rights and will care?

The Amway-like pyramid marketing company in Go was originally called American Products. We couldn’t clear that name, so we came up with a list of alternatives and checked each one. I picked Confederated Products, which I loved even more.

Clearances are standard procedure for making movies and television shows. Your “Errors and Omissions” insurance requires it. [Bad things can happen](http://www.piercelawgroupllp.com/articles/clearance-procedures.pdf) if you miss something.

But that’s for features and television. For your web shorts, you’re already doing more than most folks would. I wouldn’t stress out about it. If you feel like a little more due diligence, take screenshots of your Google results. Keep a file of everything you researched. The more documentation you have showing that you acted responsibly, the better protected you’ll be in the very unlikely case someone protests.

Finally, a word about YouTube: Thanks to the DMCA, corporations can get your stuff yanked without warning. It happened to me.

A Very Big Corporation felt the first trailer to The Nines infringed on their copyright to A Piece of Intellectual Property, and got it pulled from YouTube in less than an hour. They didn’t have to prove anything. AVBC and I have since hashed out that disagreement, but it was sobering to see that as the creator of the video, we had almost no recourse. If you attempt to appeal, YouTube repeatedly reminds you that you’re [an idiot for even trying](http://www.google.com/support/youtube/bin/answer.py?answer=185223).

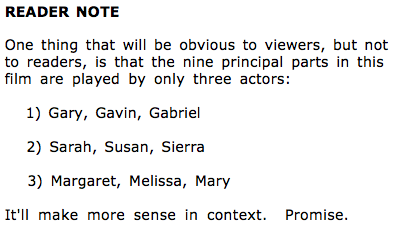

None of this should scare you away from making your shorts. Avoid the names of real companies and real people — especially classmates from junior high. But you don’t have to make your films in a hermetic, brand-free bubble in which everyone is named Smith. Unless that’s the idea for your web series. Because that’s not a bad idea.

— @josephsaid

— @josephsaid