Next week is WWDC, the annual developers’ conference at which Apple reveals all the shiny new goodness they have planned for app makers. Like everyone, I’m anticipating new looks and new APIs. What I’m not expecting is what I’d really like to see: some major changes to the App Store.

As someone who sells apps, I’d love near-real-time sales reports, link tracking and better management of promo codes.

But what I want most is for Apple to get rid of the charts.

The App Store’s best-sellers lists hurt shoppers, developers and Apple. The charts create a vicious circle that encourages shitty business models and system-gaming. They’re a relic of a time when data was scarce. They should go away.

Marco Arment [thinks so too](http://www.marco.org/2013/05/10/tire-kickers):

> Abolishing the “top” lists from all App Store interfaces and exclusively showing editorially selected apps in browsing screens would do a hell of a lot more than trials to promote healthy app economics and the creation of high-quality software.

Having been through the App Store experience with [Bronson Watermarker](http://quoteunquoteapps.com/bronson/), [Highland](http://quoteunquoteapps.com/highland/), [FDX Reader](https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/fdx-reader/id437362569?mt=8) and [two](https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/karateka/id560927460?mt=8) [variations](https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/karateka-classic/id636777828?mt=8) of Karateka, I think Arment’s on the right track. But editorial curation is only part of the solution. Apple can and should use sales data to help steer buyers towards apps they’ll like. It just has to be smarter about it.

##How charts hurt consumers

Since most people are app-buyers, let’s start there.

These lists — a sidebar in iTunes, a tab on the App Store — show what’s downloaded the most. But let’s not mistake downloads for popularity. These are apps that people may have downloaded, used once, then deleted. What you really want is a list that shows what apps that *people like you* are using and enjoying. That’s the kind of information that companies like Amazon and Netflix are terrific at leveraging.

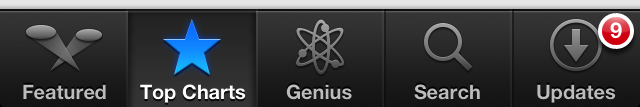

Apple makes some attempt at this in their Genius tab, which tries to find correlations based on what other apps you have installed, but I’ve never found it useful. Just because I have one to-do app doesn’t mean I’m looking for five more. (In fact, I’m probably less likely to buy another to-do app if I have one I’m using regularly.)

Consider Netflix. Netflix will show you “What’s Popular,” but it’s not a ranked list. Rather, it shows you things you might be interested in, either because of overall popularity or its own internal algorithms that calculate your preferences. Search for flashlights on Amazon and it will show you flashlights sorted based on whatever formula their data suggests will most likely result in you buying a flashlight.

That’s not how the App Store does it. Apple shows you a list of what freemium games teenagers downloaded. It’s not showing you the best games, or the most-liked games. It’s showing you what’s at the top of the charts — and because these games are at the top of the charts, they’re likely to stay there.

##How charts hurt developers

The most popular paid apps are almost always the cheapest apps, which fosters a race to the bottom. Yes, you can set your price higher — and [maybe should](http://www.tuaw.com/2013/04/01/detailed-look-at-pricing-an-app-for-the-mac-app-store/) — but since the charts are one of the only ways to get visibility on the App Store, there’s a strong incentive to go low for exposure.

Let’s say your app is priced at $10, and you sell 100 per week. Cutting your price to $5, you discover that you sell 200 per week. Cutting your price to $1, you sell 1000 per week. ((I’m making up these numbers. In reality, I’ve found price elasticity to be all over the place with the apps I’ve sold.)) In each case, you’ve made $1000. You’re making just as much money at each price point, but the $1 app would chart much, much higher in the App Store.

For that reason alone, you might pick that price even though you now have ten times the customers to support. By pricing it for the masses, you’re dealing with the masses.

Apple has tried to address the situation by adding a third list, Top Grossing, which should in theory reward the apps that sold fewer copies at a higher price. In reality, the Top Grossing iOS apps are the games with lots of consumable in-app purchases. ((On the Mac, Top Grossing does favor more-expensive apps, although Apple’s own software dominates the top of the list.))

Partly because the top-sellers lists are public information, developers feel themselves pushed to keep lowering their prices for fear of a competitor undercutting them.

That happened to us with Bronson Watermarker. We started out priced at $9.99. Three weeks later, a near-clone entered the App Store at $4.99. Does that mean we were priced too high? Or were they priced too low?

We ultimately raised our price to $14.99, while they’ve essentially abandoned their app, so my hunch is they discovered there wasn’t enough money to be made at their price.

But what if cutting the price isn’t enough to climb the charts? Developers can use [outside services like Chartboost](http://blog.chartboost.com/post/4345825883/powerful-strategy-appstore-charts):

> However, when you combine **volume with time**, then that’s where you start cracking the secret formula. If you can get high volume of installs over a short period of time, your app gets noticed and starts climbing the charts.

Most people don’t realize there’s a whole parallel industry devoted to the App Store charts. Apple could get rid of it by removing one button.

What would go in place of that “Top Charts” button? Maybe “Favorites,” with a custom-generated list of popular and well-liked apps tailored to the user. Maybe promote the “Staff Picks” section to its own spot. Hell, let’s dump “Genius” and put in both.

Should developers get to see the best-sellers chart? I think not.

I know it sounds weird to argue for less transparency, but I’d rather have more data about how my own apps are selling than a ranked list of everyone else’s. Charts encourage developers to focus on competitors rather than customers. So get rid of ’em.

I doubt Apple will announce anything like this at next week’s WWDC. But I think developers would get more out of this change than anything Apple will introduce at the conference.