Most of the questions I answer on this site are from readers who hope to become professional screenwriters. A small percentage of these readers will succeed, and suddenly face a new category of questions about What Happens Next. Having watched former assistants and other young writers cross the line into professional work, I’ve noticed that one of the biggest mysteries is money.

I want to offer a brief financial education for the newly-employed screenwriter. For most of you, this won’t apply — yet, if ever. But for others, this may be worth a bookmark, because there are some specific, unusual things you need to know. Screenwriting is a strange profession, and handling the money it generates is more complicated than you’d think.

1. Don’t quit your day job — until you have to.

Before writing this post, I asked a dozen working writers for their recommendations, and this was by far the most-often made point.

The natural instinct is to immediately quit your crappy day job once you’re hired to write something (or sell a spec). After all, isn’t that the dream? Isn’t this why you came to Hollywood? Every waiter and barrista in Los Angeles considers himself a screenwriter, so quitting your day job is an important way to distinguish yourself as a True Screenwriter, the kind who gets paid actual money to push words around in 12-pt Courier.

But don’t. Don’t quit your job right away.

Even if you sell a spec for $200K, it will be months before you see a cent. The studio will sit on your contract as lawyers exchange pencil notes about things you can’t believe aren’t boilerplate. When I was hired for my first job, (I adapted the kids book How to Eat Fried Worms for Imagine) it took almost four months before I got a paycheck. I was living off of money from a novelization, but when that ran out, I had to ask my mom for help paying rent.

Nearly every screenwriter I speak with has a similar story — you’re never as broke as when you first start making money.

Beyond the initial delay in getting paid, keep in mind that there’s no guarantee you’ll have a second writing job. I haven’t seen numbers, but my hunch is that a substantial portion of new WGA members aren’t getting paid as screenwriters two years later. A career is not one sale. As one writer friend says, “I always think of myself as six months away from teaching community college.”

If all goes well, the needs of your career will eventually force you to give up your day job. You’ll have meetings at 11 a.m. on a Wednesday, and no more excuses to offer your boss. Or you’ll be hired on a TV show, which is at least two full-time jobs. So don’t panic when it comes time to quit. Just try to leave on good terms, with back-of-mind awareness that at some point you may need to get a normal job again.

Here’s how the transition happened for my former assistants:

- Rawson finally quit working for me because the movie he was directing (Dodgeball) was in preproduction. He went from being an assistant to having an assistant in less than a week.

- Dana had a movie greenlit and another script under a tight deadline.

- Chad met with Aaron Sorkin on a Tuesday morning — and got hired in the room. He had to start working on Studio 60 that afternoon.

Each of them left, but only after the needs of their writing career made it impossible not to. In the meantime, they had regular hours and health insurance. That last part is especially worthy of attention, because it may take months to get WGA health insurance started after making a sale.

2. It’s less money than you think.

We’re used to getting paychecks that have all of the taxes and expenses taken out. Maybe you’re bringing home $850 per week. The math is relatively straightforward: you know how much you need for rent, food, utilities and whatnot. And next week, you’ll get another check.

Screenwriting is nothing like that. You get paid in chunks, from which you have to pay taxes and percentages to all the people working for you. The money shrinks at an alarming rate. Worse, you have limited ability to predict when you’ll get paid again.

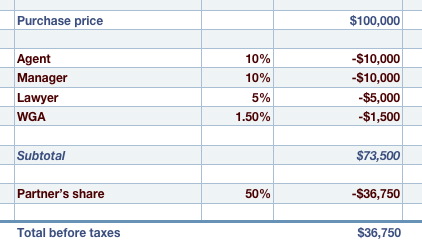

As an example, let’s say you and your writing partner sell a spec script to a studio for $100,000. That seems like pretty good money. But how much of it do you get to keep? Let’s run the numbers.

Out of all that money, you have less than $37K, and that’s before you’ve paid a penny of taxes. So don’t buy your fractional Net Jet just yet.

Some points while we’re here:

- Not every writer has a manager. I never did. Many beginning writers find managers helpful in making contacts and working on pitches. Your mileage may vary.

- While most managers get 10%, that’s not fixed by law the way it is with agents.

- You can also pay attorneys by the hour — but they’re well worth the 5%.

- You generally don’t write a check for your agent and attorney — that money is deducted by the agency when they collect from the studio for you.

- The WGA sends you a form every quarter on which you list what you’ve been paid by signatory companies. It’s your responsibility to pay dues.

Flipping through Variety, you might think that all screenwriters are rich. For instance, you might read that Sally Romcom sold a pitch for “low six figures.” That’s slanguage for $100 to $250K — still a lot of money. But if you actually looked at her deal, you’d see that the money is structured in a way that she’s unlikely to get it all at once, or even in the same year.

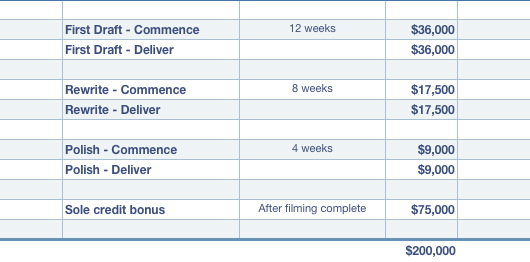

Sally is getting paid in three steps: first draft, rewrite and polish. For each step, she is being paid half at commencement, and half when she delivers. Each step has a time frame, ranging from 12 weeks for the first draft to four weeks for the polish. There is generally a four-week guaranteed reading period between each step, which means that the fastest she could expect to be paid for these three steps is 32 weeks (12 + 4 + 8 + 4 + 4).

She’ll get $125K for these three steps. The $75K sole credit bonus only happens if (a) the movie gets made, and (b) she’s the only credited writer on it. The shorthand for Sally’s deal would be “125 against 200.” The first number is what she’s guaranteed to make, while the second represents what she’ll get if the movie is made.

In order to pay her bills, Sally needs to be able to predict when she’s going to be getting more money. For years, I kept a spreadsheet tracking projects and expenses across upcoming months, to make sure I’d have enough cash to pay rent six months down the road.

3. WGA membership happens automatically

One day, you’re an aspiring screenwriter who hopes to join the Writers Guild. The next, you’re a working screenwriter who must join the guild by law.

The first time you sell a script to (or are hired to write by) a signatory company, (There are a few indie companies which are not under the WGA deal, but every major studio is) you need to join the Guild. Odds are, the guild will contact you as soon as paperwork crosses the right desk, but you can also jumpstart the process by calling the Los Angeles office.

You’ll have to pay a fee of $2,500 to join. (WGA East costs $1,500 to join. No, I don’t know why it’s cheaper.) Ask nicely, and they’ll let you spread out the payments.

The most immediate benefit to joining the guild is the health insurance. The plans and benefits are confusing but extensive, with trade-offs for Preferred Providers versus HMOs. It’s worth spending a few hours getting it set up correctly. Once you’re in the plan, you’ll need to keep working in order to maintain eligibility.

4. Splurge on one thing

Once you start making money, there’s a natural instinct to upgrade every aspect of your lifestyle, which has probably stalled out in a post-college, heavy-Ikea phase. Don’t. You’ll burn through your money and wonder what you spent it on. Instead, buy one thing you really want and can afford. Make that your reward.

For me, it was getting a dog. I’d wanted one since I was 10, and I was determined to move to an apartment that allowed dogs. I found a duplex off Melrose and got my pug. Twelve years later, he’s still sleeping at my feet. He’s a good dog and a good reminder of how my career started.

Your dog equivalent may be a car, a painting, or a 30-inch monitor. Buy it and enjoy it.

But don’t feel any pressure to act rich. I drive a six-year old Toyota. We buy store brands and clip coupons. We fly coach. (Though we’re pretty canny with upgrades. Get a credit card that pays you either frequent flier miles or hotel points, and use that for everything.)

Over time, you will probably start spending more on housing, clothing, travel and food as your standards rise. That’s okay. But spend your mad money on those few things that actually make you happy.

5. Don’t rush to pay off your student loans

Everyone wants to be debt-free, but classic federal student loans are some of the cheapest money you’re ever going to find. Until you feel confident that you’ll have enough money to last you a solid year, keep paying your normal amount.

Instead, pay off your credit cards and private student loans, which tend to have much higher interest rates.

6. Sock it away

Whether you’ve made a bunch of money at once in a spec sale, or carefully grown a nest egg through steady assignments, you’ll want to put your money in two virtual boxes. In the first, stash enough to live on for six months (including taxes). In the second box, put all the rest of the money you make — and pretend it doesn’t exist.

I’m not qualified to talk about investments, pensions or retirement, but I feel absolutely certain giving you this financial advice: save your money. Get financial advice about about smart places to put it, and then leave it alone. Except for rare occasions — buying a house, for example — you should never need to touch it. Your living expenses should be more than covered by new money coming in the door.

7. At some point, you’ll incorporate

When a studio hires me, they actually hire my loan-out corporation, which provides both tax advantages and liability benefits. I didn’t become a corporation until after Go, at which point my agent and attorney told me it was time. (I’ve often heard $200K/year as being the threshold at which point incorporation makes sense, but it may be higher or lower depending on circumstances.) It’s a lot of paperwork to set up — your attorney will do most of it — and a fair amount of responsibility, with quarterly taxes and other filings.

Like heart surgery, it’s smart to ask a lot of questions, but you ultimately want it handled by professionals who do it every day.

Before becoming a corporation, I was managing my money easily with Quicken and Excel. The added complexity of the corporation led me to hire a business manager and accountant. The best resource for finding a good business manager is other writers. You want someone responsible, reachable and thorough. Keep in mind that a business manager is not an investment guy. A business manager is writing checks to keep the lights on. The only financial advice you’ll be getting from your business manager is to spend less money, which is always worth hearing.