Roger Kamien’s description of the sonata form, a building block of the classical symphony, will seem familiar to screenwriters:

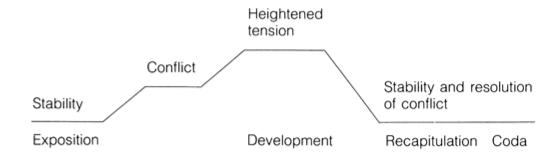

> The amazing durability and vitality of sonata form result from its capacity for drama. The form moves from a stable situation toward conflict (in the exposition), to heightened tension (in the development), and then back to stability and resolution of conflict. The following illustration shows an outline:

This line of rising action is also the basis of modern screenplay structure.

No matter how you dress it up with templates and turning points, most movies work this way: you meet your players and themes, set them against each other, let things get rough, then find a new normal.

> Sonata form is exceptionally flexible and subject to endless variation. It is not a rigid mold into which musical ideas are poured. Rather, it may be viewed as a set of principles that serve to shape and unify contrasts of theme and key.

With its long arcs and built-in act breaks, I’d argue that TV writing is even more symphonically-structured than features. Showrunners are our composers; Hollywood is our Vienna.

(I’m reading Kamien’s book on [Inkling](https://www.inkling.com/store/music-roger-kamien-7th/) for iPad, which is a remarkably good way to handle a textbook about music. The built-in tracks and listening outlines are ingenious. The chapter on classical music is currently free, and highly recommended.)