As of this afternoon, version 1.7.1 of Highland has exactly one review on its main page in the Mac App Store:

I honestly never knew how much time I was spending formatting and making pages look pretty, until I started writing in Highland. I’m a more efficient writer, focusing on what a writer should be focusing on: words. I’ve switched over to Highland for my latest screenplay and I can honestly say that I will never go back. Highland is where I will write from now on.

The highest compliment I can pay this program is that it gets out of my way. It makes me want to KEEP writing. Which is a writer’s dream.

Jmedwarren’s five-star review is so lovely that I almost don’t want to tell him the backstory: Highland wasn’t meant for writing at all.

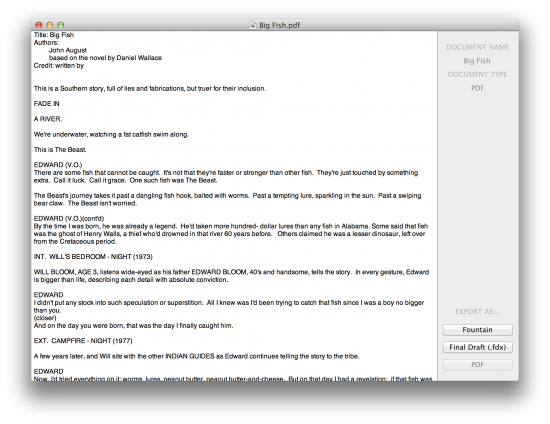

When we announced Highland in 2012, we billed it as a “screenplay utility” for converting between formats: PDF, FDX and the newly-minted Fountain. You dropped a file on it and selected a new file type.

This is what it looked like:

The initial betas had no editing view, because we assumed users would write and edit Fountain using any of the excellent plain-text editors available. Likewise, we had no preview, because we were going to export a PDF or Final Draft file anyway.

In practice, we discovered that we often wanted to make small tweaks to a file we had just converted. For example, if we needed to modify title page information, it was a hassle to have to save the Fountain text, open it in iAWriter, fix it, then re-open it in Highland.

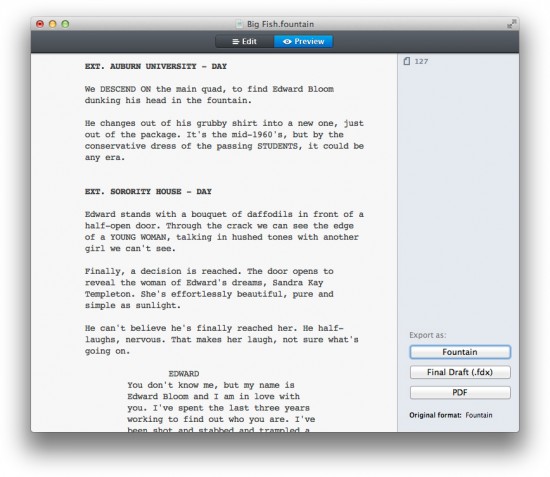

To avoid this round-tripping, we added a very basic editor and a preview. The user could switch between these views to see the changes reflected before export.

As the betas progressed, we changed the UI significantly, moving from two tabs on the top to the current sidebar. ((The sidebar was prompted largely by plans for an iPad version of Highland.)) This is what version 1.7 looks like:

By the time we shipped — almost a year later — we saw ourselves largely as a companion to Slugline. They focused on writing while we converted files. ((To this day, Slugline still has a “Send to Highland” menu command.))

Still, I started to be comfortable calling Highland a screenplay editor rather than a screenplay utility. Last year, I wrote:

Highland is a great bridge between apps, but over the last year we’ve found more and more users are simply doing their writing in Highland. It’s a full-featured editor, with spelling, versions and find-and-replace. Because it’s plain text, you can focus on the words and not the formatting.

When asked if someone could write a script in Highland, my answer was generally, “Well, you could. But that’s not really what it’s for.” I steered users to other apps as alternatives. As a company, we spent our time refining Highland’s underlying engine for parsing PDFs and dealing with edge cases.

But people kept using Highland like a traditional screenwriting app. Or perhaps it’s better to say they used Highland in lieu of a traditional screenwriting app.

People like our app store reviewer Jmedwarren saw Highland as primarily a writing tool, not a converter.

So with version 1.7 of Highland, we’re embracing the fact that we’re really a screenwriting app. We don’t do everything other apps do, but we do some things significantly better, enough so that we’re the right choice for some screenwriters.

Highland pros and cons

Here’s where Highland is actually better:

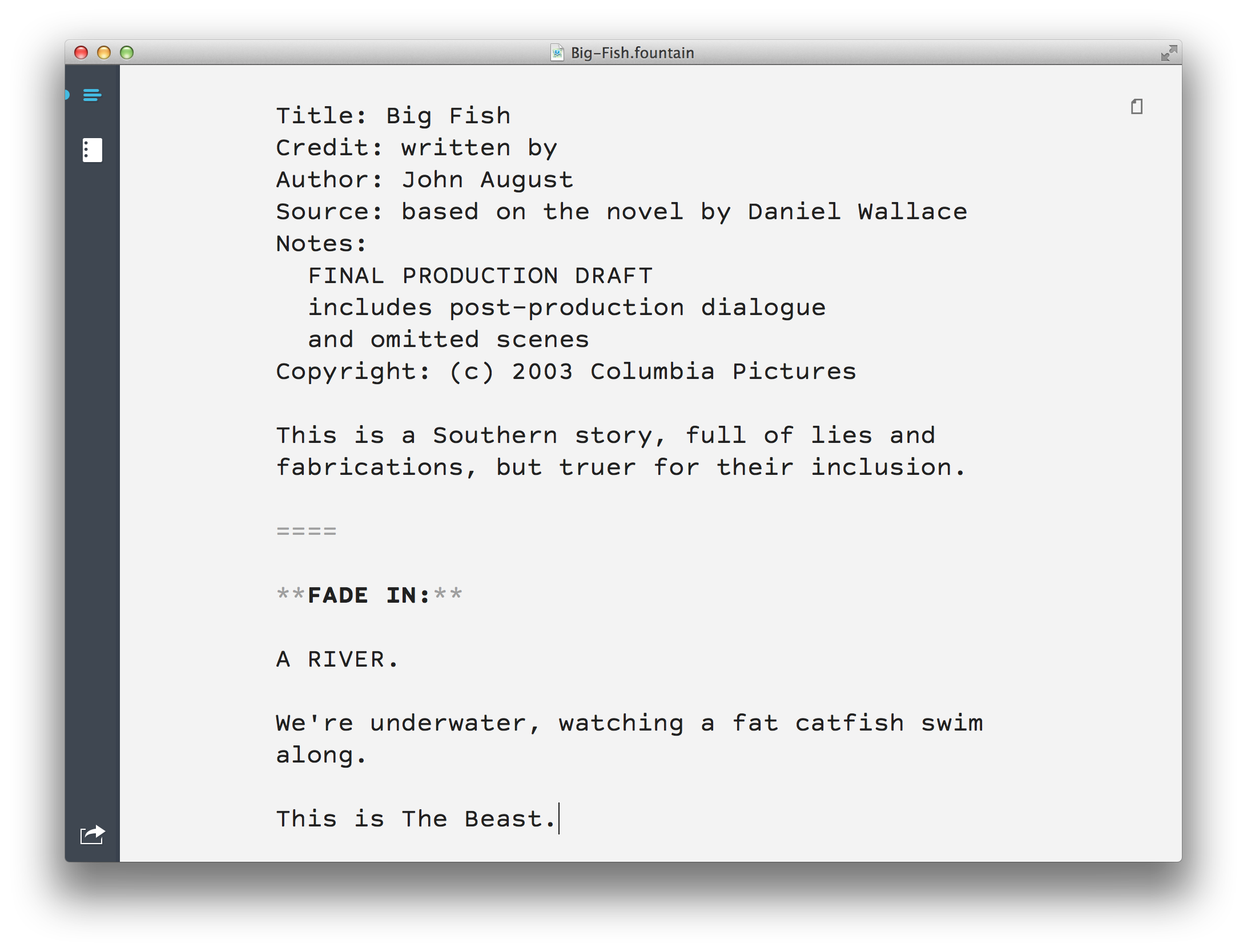

Focus. When you’re writing in Highland, it’s just the words. There’s nothing to distract you. You can’t fiddle with margins, or futz with how the pages break. Even the little bits of syntax gray themselves out so all you see is your text.

Speed. Highland is lean and mean. From scrolling to previews, Highland is blisteringly fast. Because it’s Mac-only, we optimize it using the latest Apple technologies. Because we separate editing from preview, you’re never waiting for a long document to reformat as you type.

It’s hard to market speed as a feature, because you don’t think of a screenwriting app needing to be fast. But in practice, Highland feels better under your fingers.

Typography. Highland features Courier Prime and Highland Sans, two typefaces we commissioned. Screenwriters shouldn’t have to look at ugly fonts all day.

Standards. Because we helped forge the Fountain standard, Highland does it well. We’re often the first to incorporate new specs, such as lyrics and forced character names. But you can always open Highland’s files in any plain text editor, so you’re never stuck with us. If another screenwriting app comes along that’s vastly better, you can jump ship instantly.

Dark Mode. I don’t understand why more apps don’t offer it. It makes writing in dark places — or public spaces — much more comfortable.

PDF melting. This was Highland’s breakout feature. While other apps have added it, our PDF parsing is unmatched. It’s a tricky, thankless task, but a key part of both Highland and now Weekend Read, so we keep getting better.

Active development. Highland receives regular updates, sometimes twice a month, incorporating user-requested features in almost every build. We’re small enough to move quickly, but big enough that we’re not going out of business tomorrow. When things break — and they do — we fix them fast.

Created by working screenwriters. This is the hardest advantage to show, but probably the most important factor in why Highland works the way it does. I use Highland every day for actual paid work. I rely on it, so major and minor annoyances get addressed.

I’m not the only one using it, either. Justin Marks wrote me to say he was doing his latest feature largely in Highland, in part because it made working with lyrics so much easier.

These are some of Highland’s advantages, but there are things other screenwriting apps do better than Highland — or that we don’t do at all. Our work this next year will be figuring out what we can do to make Highland more useful without losing focus.

Outlining. I use Workflowy for outlining, but I’d love an integrated outliner that smartly leverages Fountain’s section and synopsis lingo. Slugline sort of does it, but its sidebar outline is mostly a navigator rather than a writing tool. (Still, Slugline’s sidebar is really useful for long documents, and I miss it sometimes.)

Revisions. Last week, I needed to turn in a draft with small changes. I really wanted to create starred changes in the margins without having to leave the comfort of Highland. We have ideas for dealing with revisions, both within the Fountain spec and on an app level, but it’s a challenging problem. For all my issues with Final Draft, it actually does a solid job with starred changes (and more complicated production features) once you understand how it works.

Collaboration. This is a topic for a longer blog post, but collaboration can mean both two people typing in the same document at the same time (like Google Docs) or the ability to suggest edits (like Draft). Both are useful. Both are difficult. But Fountain’s plain-text background is a huge help. Fully online tools like WriterDuet may be plenty for some writers, but I have a hunch there’s more to be done here, particularly for writers working on the staff of a show.

Title Pages. This is a Fountain issue as much as anything, but creating a title page in Highland is frustratingly hit-or-miss. We had good intentions; title and author metadata is part of the file itself, as it should be. But it’s very hard to get title pages to look the way you really want. We may call a mulligan and find a better way.

All of these issues are shortcomings, not showstoppers.

For my daily use, Highland is still a better way to write a screenplay. Particularly for my first drafts, I agree with Jmedwarren in that the best thing about Highland is that it gets out of your way.

We’ve redesigned the Highland site to reflect Highland’s role as a screenwriting app. Take a look and see how it works for you.